by

Scott D. Parker

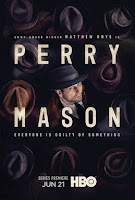

I finally finished Season 1 of the updated and re-imagined Perry Mason TV series on HBO Ma. Yeah, I know: I’m two years behind. There’s just too much good content to watch and not enough time.

Here’s a funny thing: when I pulled it up on HBO Max late last week, my time stamp was halfway through episode three. I asked my wife if she’d be up for watching. She was and, without going back to re-watch the opening two installments, we forged ahead.

The cheeky summation I’ve heard about this show is that it is not your grandfather’s Perry Mason. That’s certainly true, both in the language and the personal relationships. The moment where Della Street, assistant to E.B. Jonathan (Jonathan Lithgow), the nearly-too-old-for-this lawyer defending Emily Dodson, climbs into bed with her girlfriend, my wife asked about it. Cue said cheeky comment.

I enjoy the old TV show quite a bit, but I’m nowhere near an expert. It’s just good comfort television. As for the books, I’ve only read the first one. What’s fascinating about the first book and the 2020 series is how much alike they are. If the only Perry Mason you know is Raymond Burr, well, he’s not like Matthew Rhys but Burr is also not exactly like the character we first see in 1933. Rhys and 1933 Mason are scrappers, not afraid to poke a hornet’s nest and see what happens. It’s rather remarkable how well that type of character fit both in the Depression as well as ninety years later.

This being an origin story, I thoroughly enjoyed seeing how far down Mason was when this series began. Employed by E.B., Mason drinks way too much, is estranged from his wife and son, and constantly is threatened to have his family’s house taken away from him.

But the core quality of Perry Mason is his drive for justice. He can’t let things go when he knows there is something just under the surface. To quote Mason’s own self description when asked what he does, “He snapped out two words at her. “I fight!””

Rhys fights, both with his fists as well as his brain. The problem is that he often goes a few steps too far and says things to people like Della or his investigator, Pete Strickland, who are trying to help. I appreciated seeing Rhys try and smooth over Mason’s rough edges by the end of the season and never quite finishing the job.

It’s also fascinating to see how they inject 21st Century themes into a show set in the Depression. It’s obvious that same sex relationships and racial prejudices existed in the 1930s (and the 1950s era of the TV show) but it’s good to see it out in the open. Paul Drake, Mason’s main investigator by the end of the 2020 series, is now portrayed by Chris Chalk, an African-American. That itself brings up a lot of possibilities of narratives and themes. But I liked that Drake, a beat cop when we first meet him, has an inner integrity that is stronger that any position or job. Ditto for Della. The old TV show always showed her as all but an equal partner, but she always remained a secretary. The 2020 Della is an assistant, but she’s already enrolled in school and plans on becoming a lawyer. “A woman lawyer,” Mason says at the end. “A lawyer,” Della replied. “No modifier.”

Author Erle Stanley Gardner’s books are famous for their intricate nature. This 2020 season lives up to that bar. I did not see the ending coming and I really liked how the trial was resolved.

Oh, a quick shout out: Stephen Root, known for his comedy chops, plays the smarmy, publicity-hungry DA is all of his greasy glory. It made me want to see how many other non-comedy roles the actor has done. Loved him as I did Lithgow.

I suppose, with any origin story, you have to have older characters in places of authority that the younger characters seek to overcome. It’s pretty much the same in Season 1. So, in a very literal sense, the young Perry Mason beat a couple of old guys. You know, so it really isn’t your grandfather’s Perry Mason.

Showing posts with label 1930s. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 1930s. Show all posts

Saturday, March 11, 2023

Saturday, January 9, 2021

History Through the Thin Man Movies

by

Scott D. Parker

In that magical week between Christmas and New Year’s Day when, if you have the week off you can forget which day of the week it is, I finally did something I’ve wanted to do for a long time: Watch all six Thin Man movies.

For a gift, I was given the box set with all six movies and a seventh disc with documentaries on stars William Powell and Myrna Loy. I watched a movie per day from 26 to 31 December, writing a review per day. I had seen the first two more than once, but movies three through six was brand new to me.

For the record and to make my point, here are the movies and release dates (with links to my reviews, if you are interested):

The Thin Man (1934)

After the Thin Man (1936)

Another Thin Man (1939)

Shadow of the Thin Man (1941)

The Thin Man Goes Home (1945)

Song of the Thin Man (1947)

Three films debuted in the 1930s. The first in May 1934, a mere five months after the book’s publication. Christmas Day 1936 saw the release of the second film while it was Thanksgiving 1939 for the third. The fourth came out in November 1941, a mere three weeks before the Pearl Harbor attacks propelled America into World War II. The fifth film was released in January 1945 when the end of the war was in sight while the last landed in theaters August 1947, two full years after the V-J Day.

In watching them in a row, it was fascinating to watch history progress through the films.

If you know anything about these films, you probably know the witty banter between the two leads and the copious amounts of alcohol consumed. But modern viewers may forget that The Thin Man arrived in theaters a mere six months after the repeal of Prohibition. Sure, there may have been a lot of drinking on the down low during the 1920s, but I suspect a large percentage of the viewing audience adhered to the Volstead Act (enacted in 1920, thirteen years ago for folks in 1934) rather than risk arrest. Thus, to see Nick and Nora Charles throw back martinis one after the other must have seemed edgy. But, I suspect, more than a few watched this movie and then headed out to a bar with the full knowledge they were allowed to drink again.

Interestingly, as the movies progressed, the Thin Man series became more family friendly. Sure they could drink as much as they wanted, but it was nowhere near the amount from 1934. Heck, by the fifth film, Nick was trying to go sober and drink apple cider. Does every long-term franchise gradually sand away the sharp edges that were hallmarks of earlier movies?

Speaking of edgy things, in the first two films, Nick and Nora not only trade witty banter back and forth, but there is a definite marital/sexual chemistry that’s palpable on screen. The latter four, however, soften up the couple, making them more palatable for a broader audience.

The films’ depiction of women can seem irritating to 21st Century viewers. If you always think of Nick and Nora as a team solving crimes, that’s not really the case for the first four or five. It’s only in the last film where Nora is an active participant in things other than the finale. In fact, Nick has a really irritating habit of ditching Nora as often as possible. Even in front of her face, he’ll chastise her like she’s a kid if there are other men around. By the final film, after women held down the home front as Rosie the Riveters, the depiction of women changed. Nora was almost an equal partner.

The clothes and hairstyles are also a giveaway. You could almost name the film just by looking at a still of Loy or Powell and focusing on their hair. In the latter films, you can tell Powell was dying his hair. Loy’s hair gradually went from high-society ritzy to nearly middle-class.

The Thin Man movies sit squarely in the traditional detective movie mold. Murders are always off screen, next to zero blood, and the detective invites everyone to the same room to give a monologue where the culprit always confesses. It’s a structure that fits these kind of characters. They don’t belong in a hard-boiled noir film and they never enter one, but the world had changed around them. Nick and Nora are rarely in danger in any of the films, but the last one includes a sequence in which they feared their son was kidnapped. Definite damper on the grins and giggles. Since the kinds of books and movies were different after the war, it’s probably a good idea the franchise ended with six films. It’s also good, too, that the sixth was a return to form, because the fifth was a misstep (and my least favorite).

In all, though, I had a blast watching these films. Have you seen them all? What are your favorites?

Scott D. Parker

In that magical week between Christmas and New Year’s Day when, if you have the week off you can forget which day of the week it is, I finally did something I’ve wanted to do for a long time: Watch all six Thin Man movies.

For a gift, I was given the box set with all six movies and a seventh disc with documentaries on stars William Powell and Myrna Loy. I watched a movie per day from 26 to 31 December, writing a review per day. I had seen the first two more than once, but movies three through six was brand new to me.

For the record and to make my point, here are the movies and release dates (with links to my reviews, if you are interested):

The Thin Man (1934)

After the Thin Man (1936)

Another Thin Man (1939)

Shadow of the Thin Man (1941)

The Thin Man Goes Home (1945)

Song of the Thin Man (1947)

Three films debuted in the 1930s. The first in May 1934, a mere five months after the book’s publication. Christmas Day 1936 saw the release of the second film while it was Thanksgiving 1939 for the third. The fourth came out in November 1941, a mere three weeks before the Pearl Harbor attacks propelled America into World War II. The fifth film was released in January 1945 when the end of the war was in sight while the last landed in theaters August 1947, two full years after the V-J Day.

In watching them in a row, it was fascinating to watch history progress through the films.

If you know anything about these films, you probably know the witty banter between the two leads and the copious amounts of alcohol consumed. But modern viewers may forget that The Thin Man arrived in theaters a mere six months after the repeal of Prohibition. Sure, there may have been a lot of drinking on the down low during the 1920s, but I suspect a large percentage of the viewing audience adhered to the Volstead Act (enacted in 1920, thirteen years ago for folks in 1934) rather than risk arrest. Thus, to see Nick and Nora Charles throw back martinis one after the other must have seemed edgy. But, I suspect, more than a few watched this movie and then headed out to a bar with the full knowledge they were allowed to drink again.

Interestingly, as the movies progressed, the Thin Man series became more family friendly. Sure they could drink as much as they wanted, but it was nowhere near the amount from 1934. Heck, by the fifth film, Nick was trying to go sober and drink apple cider. Does every long-term franchise gradually sand away the sharp edges that were hallmarks of earlier movies?

Speaking of edgy things, in the first two films, Nick and Nora not only trade witty banter back and forth, but there is a definite marital/sexual chemistry that’s palpable on screen. The latter four, however, soften up the couple, making them more palatable for a broader audience.

The films’ depiction of women can seem irritating to 21st Century viewers. If you always think of Nick and Nora as a team solving crimes, that’s not really the case for the first four or five. It’s only in the last film where Nora is an active participant in things other than the finale. In fact, Nick has a really irritating habit of ditching Nora as often as possible. Even in front of her face, he’ll chastise her like she’s a kid if there are other men around. By the final film, after women held down the home front as Rosie the Riveters, the depiction of women changed. Nora was almost an equal partner.

The clothes and hairstyles are also a giveaway. You could almost name the film just by looking at a still of Loy or Powell and focusing on their hair. In the latter films, you can tell Powell was dying his hair. Loy’s hair gradually went from high-society ritzy to nearly middle-class.

The Thin Man movies sit squarely in the traditional detective movie mold. Murders are always off screen, next to zero blood, and the detective invites everyone to the same room to give a monologue where the culprit always confesses. It’s a structure that fits these kind of characters. They don’t belong in a hard-boiled noir film and they never enter one, but the world had changed around them. Nick and Nora are rarely in danger in any of the films, but the last one includes a sequence in which they feared their son was kidnapped. Definite damper on the grins and giggles. Since the kinds of books and movies were different after the war, it’s probably a good idea the franchise ended with six films. It’s also good, too, that the sixth was a return to form, because the fifth was a misstep (and my least favorite).

In all, though, I had a blast watching these films. Have you seen them all? What are your favorites?

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

The Seth Lynch Interview

Last week I reviewed Seth Lynch's debut novel Salazar and was so impressed with it I just had to know more about the author and his journey to publication. Seth was kind enough to join me for a bit of a chat about it.

.jpg) Tell us a little about your

book...

Tell us a little about your

book...

Salazar, a WWI vet, turns detective in 1930s Paris. More damaged than competent he's hired to track down a missing stock broker, Gustave Marty, by the mysterious Marie Poncelet. Along the way Salazar meets a childhood sweetheart and they rekindle their relationship. With his new love giving him a reason to live, Salazar finds the case is throwing up people ready to do him and those close to him in. It's either face the danger and find Gustave Marty or risk losing everything.

What drew you to crime and noir specifically?

I've grown into a crime/noir fan during the writing of Salazar. When I started writing, crime was a genre I enjoyed but I was mainly reading anything based in Paris during the inter-war period.

What drew me to writing crime was the scope. The period is still tightly class conscious and

I wanted a character who could mix with the incredibly wealthy and also be able to drink in seedy café's or sleep among the homeless. A detective seemed the most natural character to do this.

I was already thinking about Salazar as a man who would transform his life. The transformation would now be from war veteran with suicidal tendencies to detective.

From that point I dived into the world of crime fiction and the more I read the more I enjoyed it. Which was a good thing as I was running dangerously low on books written in Paris between the wars.

Salazar feels very fresh, was

it important to you to play with genres conventions?

Salazar feels very fresh, was

it important to you to play with genres conventions?

My intention was to write a series featuring the same character. To do that they would need a personality beyond the straight revenge, jealousy, greed motivations of a lot of noir. Also, I'd started thinking about the character of Salazar before I had a story to fit him into. He formed first and the world that best suited him was the hard-boiled cynical demimonde of noir.

There's a lot of love for the classics in there, which writers do you take your inspiration from?

In my late teens it was H G Wells. Then I went through a Henry Miller, Aldous Huxley and George Orwell phase. I was/am also heavily into surrealist literature and three books in particular influenced Salazar: Louis Aragon's Paris Peasant, Phillipe Soupault's Last Nights of Paris, and André Breton's Nadja. Graham Greene sits in their somewhere. Georges Simenon. The most direct influence came from Léo Malet – France's first noir crime writer. The problem with reading Malet is that his humour was similar to mine and, after reading one of his books, I tended to start thinking in his voice. I've gained more control over that now.

Recently I read Two Way Split by Allan Guthrie. About half-way though I had a eureka moment. I realised I'd been forcing things in Salazar and as a result had to do a lot of re-writing. The thing that clicked when reading Guthrie was the naturalness of the voice. For me that means relaxing as I write, to stop thinking about how to write a sentence and start thinking about how I'd say it.

1930's Paris is richly evoked, how much research did you do?

I'd read histories of Surrealism and biographies of Henry Miller and Hemingway. I then read Gary Corby's Pericles Commission, which is set in Ancient Greece, and I realised that I was also writing an Historical crime novel. That really hadn't occurred to me before, I'd thought of it as a hard-boiled or noir or a detective novel. At that point I jumped into to research mode.

There are countless memoirs and

books covering angles like Black American Jazz Musicians in Paris,

The Sewer Workers of Paris. I could lose hours flicking through

Brassaï and André Kertész photographs. Even books with no other

merit would let me know how much a coffee costs or what the ex-pats

were gossiping about. My reading is generally about 4-1 fiction to

non-fiction.

What do you think makes post-War Europe such a perfect setting for noir?

I read an article by Phillipe Soupault, written in the 1950's, where he talked about the atmosphere in the years leading up to the formation of Surrealism (1924). He mentioned that many of his friends from before and during the war had gone on to kill themselves. There was Jacques Vaché who killed himself with a deliberate opium overdose in early 1919. Jacques Rigaut, the Dadaist poet, who declared, in 1919, that he'd kill himself in ten years. He shot himself through the heart in 1929. You could say there were a lot of walking dead in that decade after the war. It wasn't only suicide: my great-grandfather was gassed at The Somme in 1916, his lungs finally packed up in 1929. My gran was born in 1919, after he'd been killed but before he died.

Then there were amputees begging

for food because they gone to war, lost a limb, and could no longer

return to their previous occupations. Think of Otto Dix's painting of

the card playing invalids. Being conscripted to fight then having to

beg for food is about as noir as you can get.

Added to the mix is the political ferment – fascists in Italy and Germany, Communists in Russia, all represented on the streets of Paris. The government was at times inept or corrupt, the police force rife with corruption. France during most of the '30s was one step away from civil war.

Plotter or pantser?

Pantser. My fist draft is normally a 60-70,000 word synopsis which I try to write as quickly as possible. I normally have a good idea of the theme and will do some background reading before I start. I'll spend the rest of the year re-writing, editing and doing further research. I've been promising myself that the next time I'll be a planner.

How does it feel to have the book out there finally?

Fab. I feel like it's a vilification for all the hours spent writing. Also, I've had some good feedback and it encourages me to keep going when there are a million and one reasons to stop. I also got to join the CWA which was an ambition while writing Salazar.

What's coming up next from you?

Salazar #2, A Dead American in Paris, is nearly done and I scribbled out a first draft of Salazar #3 to work on next year. I'm also drawing to the close on The Doorbell Maker's Daughter. It's set 50 or so years in the future. A detective is hired to track down a rich industrialist's daughter. He calls on a few of her friends who give him an address in Bristol. He finds the daughter living with her boyfriend, unaware of any reason why her father would think she was missing. That night she's murdered. The father denies ever hiring the detective who's now the number 1 and only murder suspect.

.jpg) Tell us a little about your

book...

Tell us a little about your

book...Salazar, a WWI vet, turns detective in 1930s Paris. More damaged than competent he's hired to track down a missing stock broker, Gustave Marty, by the mysterious Marie Poncelet. Along the way Salazar meets a childhood sweetheart and they rekindle their relationship. With his new love giving him a reason to live, Salazar finds the case is throwing up people ready to do him and those close to him in. It's either face the danger and find Gustave Marty or risk losing everything.

What drew you to crime and noir specifically?

I've grown into a crime/noir fan during the writing of Salazar. When I started writing, crime was a genre I enjoyed but I was mainly reading anything based in Paris during the inter-war period.

What drew me to writing crime was the scope. The period is still tightly class conscious and

I wanted a character who could mix with the incredibly wealthy and also be able to drink in seedy café's or sleep among the homeless. A detective seemed the most natural character to do this.

I was already thinking about Salazar as a man who would transform his life. The transformation would now be from war veteran with suicidal tendencies to detective.

From that point I dived into the world of crime fiction and the more I read the more I enjoyed it. Which was a good thing as I was running dangerously low on books written in Paris between the wars.

Salazar feels very fresh, was

it important to you to play with genres conventions?

Salazar feels very fresh, was

it important to you to play with genres conventions?

My intention was to write a series featuring the same character. To do that they would need a personality beyond the straight revenge, jealousy, greed motivations of a lot of noir. Also, I'd started thinking about the character of Salazar before I had a story to fit him into. He formed first and the world that best suited him was the hard-boiled cynical demimonde of noir.

There's a lot of love for the classics in there, which writers do you take your inspiration from?

In my late teens it was H G Wells. Then I went through a Henry Miller, Aldous Huxley and George Orwell phase. I was/am also heavily into surrealist literature and three books in particular influenced Salazar: Louis Aragon's Paris Peasant, Phillipe Soupault's Last Nights of Paris, and André Breton's Nadja. Graham Greene sits in their somewhere. Georges Simenon. The most direct influence came from Léo Malet – France's first noir crime writer. The problem with reading Malet is that his humour was similar to mine and, after reading one of his books, I tended to start thinking in his voice. I've gained more control over that now.

Recently I read Two Way Split by Allan Guthrie. About half-way though I had a eureka moment. I realised I'd been forcing things in Salazar and as a result had to do a lot of re-writing. The thing that clicked when reading Guthrie was the naturalness of the voice. For me that means relaxing as I write, to stop thinking about how to write a sentence and start thinking about how I'd say it.

1930's Paris is richly evoked, how much research did you do?

I'd read histories of Surrealism and biographies of Henry Miller and Hemingway. I then read Gary Corby's Pericles Commission, which is set in Ancient Greece, and I realised that I was also writing an Historical crime novel. That really hadn't occurred to me before, I'd thought of it as a hard-boiled or noir or a detective novel. At that point I jumped into to research mode.

|

| Brassai - Paris street |

What do you think makes post-War Europe such a perfect setting for noir?

I read an article by Phillipe Soupault, written in the 1950's, where he talked about the atmosphere in the years leading up to the formation of Surrealism (1924). He mentioned that many of his friends from before and during the war had gone on to kill themselves. There was Jacques Vaché who killed himself with a deliberate opium overdose in early 1919. Jacques Rigaut, the Dadaist poet, who declared, in 1919, that he'd kill himself in ten years. He shot himself through the heart in 1929. You could say there were a lot of walking dead in that decade after the war. It wasn't only suicide: my great-grandfather was gassed at The Somme in 1916, his lungs finally packed up in 1929. My gran was born in 1919, after he'd been killed but before he died.

|

| Otto Dix - Die Skatspieler |

Added to the mix is the political ferment – fascists in Italy and Germany, Communists in Russia, all represented on the streets of Paris. The government was at times inept or corrupt, the police force rife with corruption. France during most of the '30s was one step away from civil war.

Plotter or pantser?

Pantser. My fist draft is normally a 60-70,000 word synopsis which I try to write as quickly as possible. I normally have a good idea of the theme and will do some background reading before I start. I'll spend the rest of the year re-writing, editing and doing further research. I've been promising myself that the next time I'll be a planner.

How does it feel to have the book out there finally?

Fab. I feel like it's a vilification for all the hours spent writing. Also, I've had some good feedback and it encourages me to keep going when there are a million and one reasons to stop. I also got to join the CWA which was an ambition while writing Salazar.

What's coming up next from you?

Salazar #2, A Dead American in Paris, is nearly done and I scribbled out a first draft of Salazar #3 to work on next year. I'm also drawing to the close on The Doorbell Maker's Daughter. It's set 50 or so years in the future. A detective is hired to track down a rich industrialist's daughter. He calls on a few of her friends who give him an address in Bristol. He finds the daughter living with her boyfriend, unaware of any reason why her father would think she was missing. That night she's murdered. The father denies ever hiring the detective who's now the number 1 and only murder suspect.

Labels:

1930s,

Dada,

P.I,

Paris,

Salazar,

Seth Lynch,

Surrealism

Wednesday, October 9, 2013

Salazar by Seth Lynch

1930's Paris is a setting ripe with potential for the noiriste, thrumming modernity sitting cheek by jowl with the squalid remnants of the previous century. Bohemians, expatriates, dubious businessmen and the occasional vamp with cinematic bounce. And, in this case, Salazar; an Englishman abroad, world-weary but given to bouts of concerted decadence, a battle-scarred veteran of Passchendale and the Somme, now passing his time as a private detective.

.jpg)

A not particularly experienced one it has to be said. With just two cases in his filing cabinet Salazar has spent more time playing chess with his landlord than running down villains, but when Marie Poncelet, a young woman with a reticent demeanor, comes to him wanting to find a mysterious Belgian stockbroker, Salazar's interested is piqued. The missing man, Gustave Marty, has a suitably shady past, an eye for the ladies and other people's money, and everywhere Salazar goes doors are slammed in his face. Reputations are fragile things after all.

Salazar's hunt takes him through Paris' swanky financial houses, where the money men may have just as much to hide as the elusive Marty, and connections which are just as deadly. He is a dogged investigator though, not one to back down at the first hard blow, and a chance encounter with an old flame from his life in England brings a tentative hopefulness into Salazar's ennui-riddled life. It also brings a point of vulnerability and if he wants to enjoy a future with his rediscovered love the case will have to be solved, no matter what the danger.

And what of Marie Poncelet, Salazar begins to wonder. What could a girl like her possibly want with a man like Marty? Is she a jilted lover, a victim of his scheming, or something else entirely?

Salazar is a cracking debut, part noir, part period romp, with touches of nifty wit leavening the dark subject matter. The eponymous hero is a neat spin on the classic P.I, deeply troubled not beyond redemption, a fighter when he needs to be and a thinker the rest of time, with a smart eye trained on the city at this particular point in history. There are allusions to surrealism and Freud, reflections on financial dirty dealing and the effects of warfare on the people left behind. Lynch has clearly researched his setting thoroughly and Paris of the 1930's is richly evoked, familiar enough that visitors will delight in recognising the spots they know, transformed by a layer of grubby glamour so deftly conjured that I read it craving Gitanes and black coffee.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)