The second season of Penknife is out -- the podcast about writers who may or may not have written about crime, but who definitely committed it -- and I'm happy to say that it lives up to the excellent standards set by the first season.

Season one, as I've written about on this blog here, focused on Norman Mailer, Jerzy Kosinski, and Jack Henry Abbott, their writings and crimes. Season two is more concentrated in nature, as the podcast's creators, Corey Eastwood, Santiago Lemoine and Ramona Stout, discuss the intertwined lives and nearly simultaneous deaths of two people. These are British playwright Joe Orton and his long-time friend, lover, and partner, Kenneth Halliwell. The two met in 1951, when Orton was 18 and Halliwell 25, and their relationship ended on August 9, 1967. That is the night when Halliwell struck Orton nine times with a hammer while Orton was sleeping and then swallowed 22 pills of Nembutal with a cup of pineapple juice. Halliwell died quickly, but Orton, who almost certainly didn't feel anything after the first blow hit him, lingered on unconscious for hours. By the time a chauffeur came knocking the next morning to pick Joe up to take him to a meeting with film director Richard Lester, for whom he had written a script called Up Against It (at one time to star The Beatles, then, later, Mick Jagger and Ian McKellan), Orton was dead, too. If you're a fan of Orton's plays or read John Lahr's biography about him called Prick Up Your Ears or saw the Stephen Frears film of the same name, with Gary Oldman as Orton and Alfred Molina as Halliwell, you know the basics of this story.

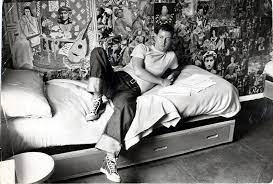

At its core is the way the arc of their relationship developed over time. Once Halliwell had been Orton's mentor, his educator if you will, and they collaborated on both various public pranks (amusingly described in the podcast) and artistic work, specifically novels. Both were involved in regional theater. Both were living as gay men in a country where homosexuality was still technically illegal (until 1967), and because the two shared the same small apartment for years, they knew nearly every detail about each other's lives. But there came a time when it became clear that Orton had a depth of talent that Halliwell didn't, and while Orton in a few short years turned out plays that jolted English theater and made his name -- Entertaining Mr Sloane, Loot, What the Butler Saw -- the artistic aspirations of Halliwell languished. Penknife details his struggles and how, as well, Halliwell never possessed much social grace. While Orton, like his plays, was witty and funny, Halliwell could be maladroit to the point of attracting scorn from others. While Halliwell suffered from early baldness (later hidden by a wig), Orton, vain, had good looks and worked hard on his physique. As time passed and the two remained close, though not precisely in the way they had been close years earlier, the resentment in Halliwell grew and grew. The pressures inside him built. And these pressures increased, you could say, upon a foundation inside Halliwell that had been damaged from quite early. I'll let the podcast fill you in on what Halliwell went through as a child. In all honesty, it's not easy to feel much sympathy for him as an adult and one can't say that his early trauma excuses or minimizes murder, but it does help put his actions in a context that gives us a full picture of the man.

And as for Orton? Here also context is key. We know Orton as a victim of a terrible crime and as a man who had to live through a period where he could be arrested for having sex with another man. We know him as a playwright who mocked, attacked, broke down, and made ridiculous every mainstream moral code he could. But, as Penknife examines, there was another side to Orton, one uncomfortable to talk about, now as much as ever, and it is this side that the podcast zeroes in on in its final two episodes. It wrestles with the eternal question of how do you look at great works of art from a problematic artist. In Orton's case, the question is especially tangled because the artist, apart from his predatory acts (we're talking pederasty here, sexual tourism with teenage boys in Tangier), strongly stands as an admired iconoclast, a gay icon, a devoted and hilarious thumber of his nose at authority, the establishment, and homophobes everywhere. Penknife gets into all this stuff, and it does so with intelligence, directness, and what I love most when these complicated things are explored: nuance. One can discuss even awful human actions with nuance, using history, at least in part, to establish context. One can view a complex person from various angles at the same time and hold all these conflicting aspects of that person in your mind without total condemnation or any whitewashing. With its focus on writers who've committed crimes -- good writers -- Penknife has hit upon a particularly fertile area of investigation, and the conversations that its three creators have among themselves, debating, questioning, turning things over from various directions and through different prisms, injecting serious matters with humor, is a pleasure to listen to.

I'm looking forward to season three.

No comments:

Post a Comment