By Jay Stringer.

An earlier version of this article was published several years ago at Panels.Net, a now defunct comic book website.

I'm often asked to explain dyslexia. The trouble is, I really can't. It's not that I don't know how my brain works. It's that I don't know how your brain works. Dear reader. Dear neurotypical reader. If I can figure out what you see when you try and read things, and the places in your brain that you store information, then maybe, maybe, I can start to explain how my brain is different.

I often wonder about colour blindness. How was it discovered? Obviously, now we know it's a thing. And it has symptoms. And people can be diagnosed, and there's a wealth of research into it. But back before we knew it was a thing, how did we find out it was a thing? Two people looking at the same colour, the assumed same point of reference, how did they each realise they were seeing two different things? How did person A come to realise they were seeing something different in 'red' (for example) to person B? What did that conversation look like?

You can lose whole hours in the day trying to figure out how the inside of your head works, and whole days trying to figure out if someone else's head works the same way. (Whatever you do, don't become aware RIGHT NOW of your tongue. It's just sitting there in your mouth doing nothing. No, now you made it move. Oh god, it moves. And it's just there....all the time. What the hell? Creepy.)

What I can tell you is what dyslexia isn't. It's not about spelling. Not really. That's a symptom. Dyslexia is about the way my brain processes information. Both on the way in and the way out. And about where I file that information when I'm not using it. I have amazing long-term memory. And terrible working memory. What's working memory? It's loosely similar to RAM on a computer. The steps I need to go through to make a cup of tea are stored in my long-term memory, but when I'm actually in the middle of making one, which step I'm on in that process is stored actively in my working memory. And mine is....goofy. Allied to that, colours have frequencies. On the screen you're looking at right now, you can adjust the brightness and contrast to make an easier reading experience. Our eyes and brains are doing that naturally all the time, because every colour we look at has a frequency. Some higher, some lower. Dyslexics are often incredibly sensitive to some of those frequencies, especially to white. White can overpower us, and that's a large part of why we can lose words on a page. Dyslexics also often have colours that can neutralise the effect, and getting glasses with lenses adjusted to the right tint can make reading a lot easier. (My colours are red, yellow, and some greens.)

I can't tell my left from my right. (I actually can now, mostly, at forty years of age. Through muscle memory. Through learning a few cheats over the years. But there's a delay of a few seconds while my brain accesses the memory.) I struggle to count money because it's a logical sequence and utilises my working memory. I can't say the alphabet all the way through. I can't say the months of the year backwards. And yes, I have varying degrees of difficulty with reading and writing.

I’m going to ask you to do a strange thing. Right now. I’m going to ask you to stop reading this piece. Just for a few seconds. I’d like you to stop reading, and think about how much you actually read each day. Think about road signs. Think about labels on food packaging. Think about the instructions on whether the door you are approaching needs you to push or pull. Think about walking into the shop for household supplies, and all the little bits of reading you do as you walk around filling your trolley. Now think about living the same life, going about the same routines, without being able to read, or with reading being extremely difficult. How would that affect you? It would be pretty hard, right?

The world simply isn’t designed for people who struggle to read, and they get left behind in small ways each and every day. One of the main reasons I'm here today, writing this piece, is because comic books pulled me out. Comic books taught me to read. Comic books gave me the basic building blocks I needed to work around the simple things my brain just couldn't seem to do.

Most of this is with the benefit of hindsight, of course. A dyslexic child doesn’t know they are dyslexic. At the time I thought nothing of the afternoons I would spend separated from the class, reading very difficult books about a dog and a ball and a boy. My grandfather would spend hours with me after school, trying to teach me the difference between a verb, an adverb and a noun.

I still probably don’t know what they are, but it doesn’t matter. None of the rules of grammar or spelling are essential in learning to read. They become guides later on, a road map for staying on the right course, but they are not where the journey needs to start.

What’s needed is clarity and context. Given those two things we can learn anything, from basic reading to advanced nuclear physics. But we also need to think about the way we process information, about how we know where to store things in our memory and about what keeps us moving forward, adding to what we know.

Let’s boil this down to Story, Plot and Narrative.

Story.

Story is the what. A collection of events. You do this, then you do that, then you eat a dinner, then you do something else, then we get to the end. It’s the basic data of anything that we learn. Okay, here’s a problem for us straight away; dyslexics can’t really do order. We don’t do logical progression. Give us a whole bunch of data, and on it’s way into our heads it scatters like a pack of playing cards thrown across a room.

Plot.

Plot is when. This is the road map to move through the story. It tells us when to climb and when to rest, when to turn and when to hold. For learning, this is the guide that tells us when to take on information and where to store it. Dyslexics have no problem taking on information. We’re taking it in all the time. The problem is storing it. Where did we leave that thing that we needed? How to we find it again? How is it relevant to what we’re doing?

Narrative.

This is how and why. Narrative takes story and plot and fleshes them out with context and motive. You do this, which then leads to that because of the other, then you eat because you’re hungry and haven’t had any food since whenever, and you like the taste of the bread. Then you do that thing that you’ve been doing every day for twenty years, driven by the memory of something, then we get to the end and you lay down for a well-earned rest.

We all combine information in different ways, and at different speeds. Some can add story and plot together in a mathematical equation that leads to narrative. Dyslexics like myself can’t learn anything without a narrative to hold on to. Why am I being given this information? What does it do? What is it relevant to? What similar thing should I store it next to in my head?

The books I was being given to read at school were no help. Oh, hey, there’s a picture of a dog. And a squiggle next to it that probably means “dog.” So what? Nothing’s happening here, there’s no information for me to file away, and if I do store it, where do I put it? What is it relevant to? And that’s a ball. Nice. But the ball is not moving, I’m bored.

There is a simple thing you could do for all children as they learn to read, but for a dyslexic it could be life changing; put a comic in their hands.

Comics as a medium rely on clarity and context. They are pictures and words being used in small panels to tell a story. Essentially they are hieroglyphs. They are a form of communication older than any of these words I'm typing here. Older than the grammar we are taught in schools. Almost as old as the oral traditions we've built everything on.

The real art of telling a story in a comic is in giving the illusion of movement between the panels. Things happen, your eye moves from one image to the next and your brain builds a structure to carry the information.

It’s the perfect medium for learning to read.

Staring at a page of prose, even now as an adult, can be a challenge. The words are just black marks on a page. They just sit there. They don’t do anything unless they connect with the right memory, the right piece of data in your head, to give them some purpose.

Films, on the other hand, do too much. They give you everything. All the movement, all the talking, all the emotion. Watching a film is essentially a passive process for your brain.

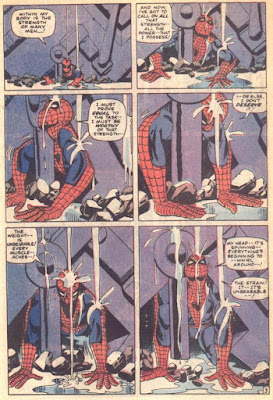

Take a look at this example, from Amazing Spider-Man #33, with art by Steve Ditko and words by Stan Lee:

This is something that comics can do better than any other medium. Ignore the words for just a moment and look at the images. In fact, imagine there were no words. Would you still understand the story? Absolutely, you would. Steve Ditko has given you a road map. Look at both the pictures and the panel construction. There is movement. There is narrative progression. The panels start as small, compact spaces, with Spidey as a tiny little figure underneath the machinery. It’s claustrophobic. It’s hopeless. Look then at the third and fourth panel. As he pushes upwards, so the panels push, they stretch. Then again with the fifth and sixth panels. They create the sense of movement, and Spidey’s growing size within each frame tells us about his own strength and confidence. There is a lot of heavy lifting going on (pun very much intended) between Steve Ditko’s pen and our brains. The words become an added extra.

You don’t need to be dyslexic to appreciate that example, of course. It’s one of the purest examples of the language of comics, and readers have been marvelling over the page for decades. It would be difficult to create that sense of movement, that primal understanding of narrative, with prose. A film could tell the same story, (And Spider-Man: Homecoming did) but then the screen would be doing all the work.

What happens here is that you do the work. Your brain picks up on the visual cues left by Ditko, and fills in the gaps. This is why I use it as an example for what dyslexics can gain from reading comics. A comic book trains your brain. It works the right muscles and, if you’re struggling, they can teach you to read.

You see images for context, you see the words that go with them, and your mind learns to fill in the blanks. You learn to build the narrative as you go. As a child, I suddenly got it. I had a structure, a guide for processing the information I was taking in, and where to store it. I had a reason to keep moving through the pages.

If you know someone who is a struggling reader, give them a comic. Give them the best comic in your collection. You might change their life.

Jay's new mystery thriller Don't Tell a Soul is released July 26th. Available wherever books are sold. There's a Dyslexic Reader Edition - a paperback formatted for dyslexic readers- available with the ISBN 978-1-9168923-2-3.

Epub Quick Links: Apple. Amazon US. Amazon UK.

No comments:

Post a Comment