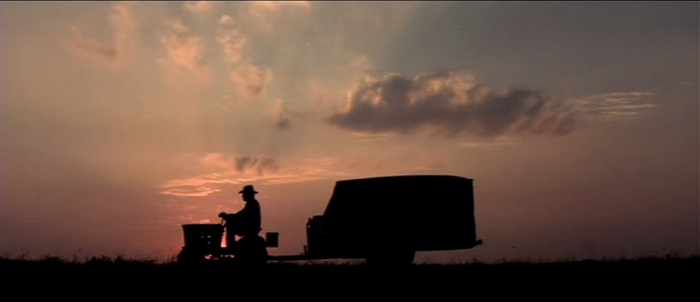

Now, all this talk of Lynch reminded me of a piece I read years ago about him, after his most straightforward movie, The Straight Story, from 1999, came out. In the piece, the reviewer made the point that in this story which has little of the usual Lynch weirdness, but a very simple narrative about a sick old man wanting to go see his brother before he dies (though he does drive the 240 miles from Iowa to Wisconsin by tractor so there is some oddness), one can truly see that what makes Lynch so effective a filmmaker is not the weirdness per se. Yes, without question, you sit down and watch a Lynch movie to enter the world created by his complex and bizarre imagination, but it's his mastery of cinematic technique that puts that vision across. This was never so clear as when The Straight Story came out. In this movie Lynch has to rely on all the conventional tools of cinematic storytelling, and if it wasn't already, it becomes crystal clear how Lynch is a great director of actors, a master of pacing and the building of narrative momentum, a director who knows exactly how to work on an audience's emotions. This goes with the tight control he exercises over editing, lighting, camerawork and so on. He had proved this earlier, actually, when he made The Elephant Man, his second feature (after Eraserhead), a story that is Lynchian in its embrace of the beauty in so-called freakishness but whose narrative is, again, straightforward. A guy who had made one feature, and a non-narrative one at that, and here was Lynch directing Anthony Hopkins, John Hurt, John Gielgud, and Anne Bancroft with the assurance of a veteran. The greatness of Lynch, my friend and I agreed, comes in large part from how he has such formal control. It's that technical mastery, put in the service of his distinctive vision, that allows him to get emotional effects whether he's telling a conventional story or not or using dialogue or not. You feel a Lynch movie even when you don't quite know what, at that moment, is going on.

So what would be the equivalent of cinematic technical mastery in writing? my friend and I asked ourselves. No camera to place here, no music or editing effects to employ, no lights and shadow to manipulate for mood. How do you get your intended effects on the page? Through language, obviously, and so it stands to reason that the more able and versatile you are with what you can do with words, the more you'll be able to accomplish. Yes, one should be able to write elegant prose of a silky smoothness or coarse prose that cuts and bites. You should be able to compose with equal skill in long winding sentences or short blunt sentences, in extended paragraphs or short ones, with lots of dialogue or for pages and pages, in fiction, no dialogue. It's not because you want to show off or write something that's pretty or "well-written". It's because the more facility you have with language, the more you'll be able to pull off what your ambitions would like you to do. Most importantly, the better your chops, the more you'll be able to move, engage, and engross a reader. You can evoke the emotions in that reader you want to evoke.

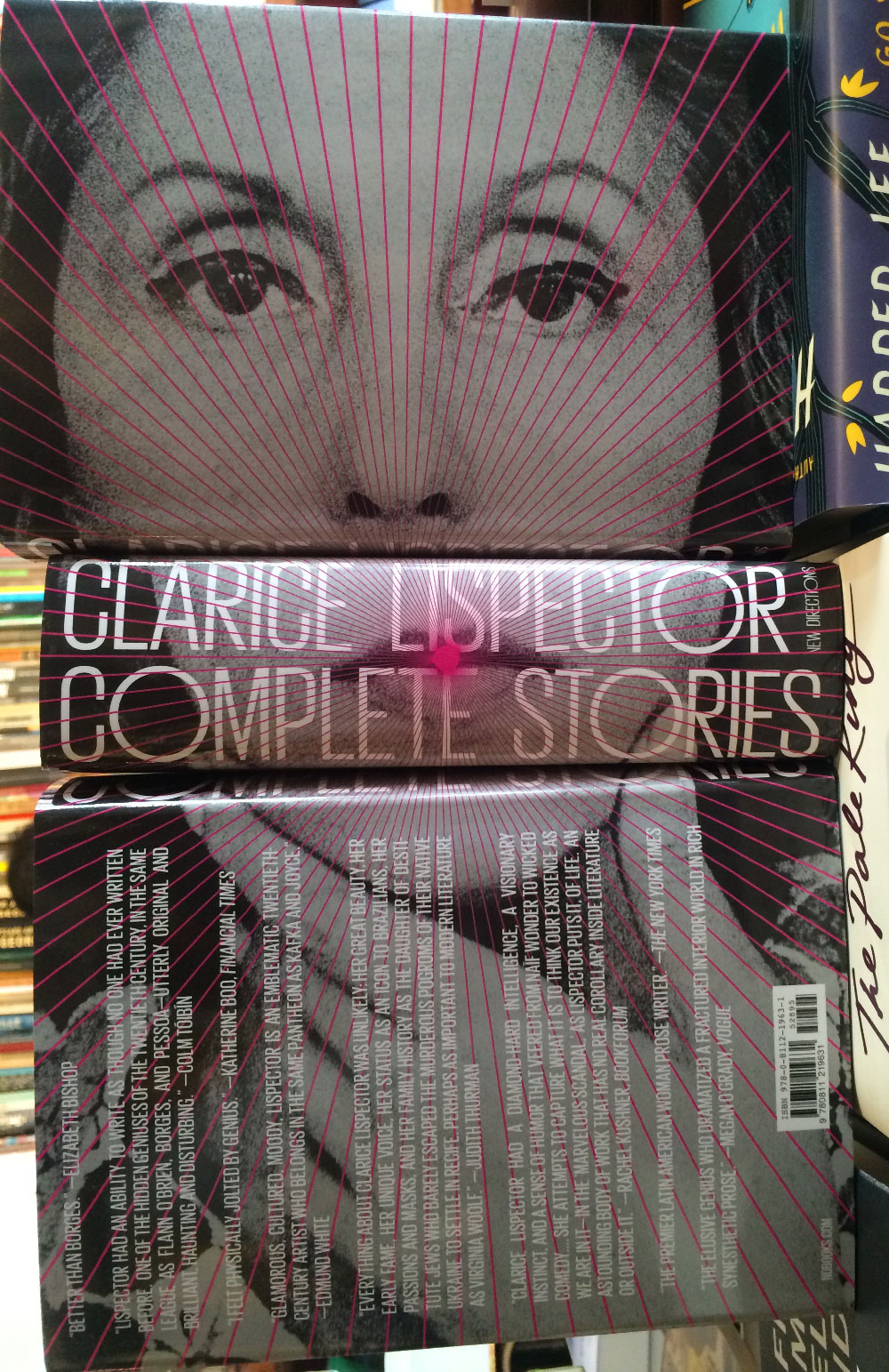

My friend happened to be dipping every day into the Complete Stories of Clarice Lispector, and we began to talk about her. She's a perfect example of what we were talking about, someone akin in her way to David Lynch. You read a Lispector story (or novel), and it sounds like nobody else in the world. She has way of putting you inside a character's head and then bombarding you with that character's perceptions, both elevated and mundane. Or she may begin a fairly linear story, but that story will almost never go where you think it will go, if it continues to develop as a linear story at all. Her stories disorient, and you don't even always grasp exactly what she's talking about, but you most certainly feel what's going on in the story. At the very least, you have a sense, an intimation, of something powerful. She gets these effects because she feels what she feels and then can translate it all to the page through a use of language that seems to have no limits. Interest can come through telling a straightforward story, or not. And, again, it's not that she writes "pretty" or "beautifully", though she can. We're not talking literary for literary's sake, whatever that's supposed to mean. It's that Clarice Lispector is an example of a writer who has an instrument she can play in so many different ways, it expands what she can write about. Because of those tools, she has more approaches open to her than someone working with less.

It goes without saying I'm sort of talking ideals here. What is writing if not the daily meeting with your own limitations? Try as I might, I do not expect to develop the facility or originality with language of Clarice Lispector. And it also doesn't need mentioning that if you don't have much to say, having all the language skills in the world won't make you a writer many people will continue reading. But be that as it may. No matter what you're going to write, everything begins with how you're going to say what you intend to say, and for my part, this desire to improve and expand the stylistic tool kit so that I can do more on the page with more versatility is one that I can't see ever burning out.

2 comments:

Great post here on Lynch--terrific points. And coincidentally, I've felt myself drawn each time I've seen it in a bookstore toward the Lispector collection, though I've only read one or two of her stories before in anthologies. This post may have pushed me over the edge toward getting it. Thanks for the fine perspectives, as always!

Art - Lispector is well worth it. Demanding but great.

Post a Comment