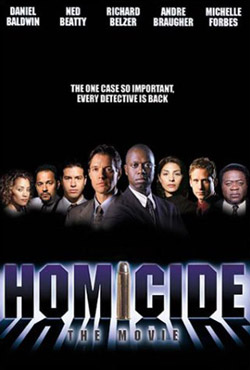

To celebrate the news that Homicide has finally been cleared of all the legal obstacles that were preventing it from being streamed (Peacock will have it starting August 19th), I decided to repost a piece I wrote 7 years ago for Criminal Element about the very first episode of Homicide, which I saw when it first aired 31 years ago. Hard to believe it was that long ago, really, but it was, and as much time has gone by, as many great shows have aired since then, the series remains one of my all time favorites. That goes for crime shows or any kind of shows. I used to tape episodes on my old VCR, so I've seen a lot of the episodes more than once, but it has been years now since I've watched any (I no longer have a VCR), so I'll be excited, when it does start on Peacock, to go back to the show and the great actors and actresses who were on it. There are 122 episodes in all and the TV film, Homicide: The Movie that wrapped it up. What a run it was. But anyway, here's the piece I wrote about the premiere episode, and how that episode got me hooked for the years of intense and pleasurable viewing that were to come.

First in Series: Homicide: Life on the Street

In January, 1993, right after airing Super Bowl XXVII, NBC premiered the series Homicide: Life on the Street. I remember watching the first episode then because I had seen the promo spots for it during the game, and it appeared to be an intriguing enough police show to give it a try.

It’s amusing now to think which names I knew from among the creators and original cast and which I didn’t. NBC played up that filmmaker Barry Levinson was a driving force behind the show, and this did impress me. He’d made films I’d liked such as Diner, Tin Men, and The Natural, and as a Baltimore native who’d made good films set in the city, his involvement suggested that the Baltimore-set production might be something other than a conventional cop show.

The names of the actors in the large ensemble cast definitely caught my attention as well: Jon Polito from his Coen Brothers’ film work; Ned Beatty for countless movies; Yaphet Kotto from Blue Collar and Alien, among others; and Richard Belzer, an oddball comedian I knew from Saturday Night Live appearances. But Andre Braugher—who as Detective Frank Pembleton became the show’s most compelling character—I barely knew, and I’d never even heard of David Simon, a Baltimore Sun reporter on whose 1991 non-fiction book, Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, the show was based.

Homicide ran from 1993 – 1999 on NBC for a total of 122 episodes. It concluded in February 2000 with Homicide: The Movie, in which nearly all the main cast members who had been on the show appeared. Despite a devoted following and critical acclaim, the show never pulled in very strong ratings, and throughout its run it seemed always to be in danger of cancellation.

Homicide ran from 1993 – 1999 on NBC for a total of 122 episodes. It concluded in February 2000 with Homicide: The Movie, in which nearly all the main cast members who had been on the show appeared. Despite a devoted following and critical acclaim, the show never pulled in very strong ratings, and throughout its run it seemed always to be in danger of cancellation.

Still, it did survive for those seven years, and what a consistently high-quality seven years they were. I watched every episode made, and that was during the period it aired, usually by taping the episode on VCR and playing it back soon afterwards (a way to skip the commercials). But how much of the show’s excellence, to go back to that January 1993 night, was apparent in Homicide’s pilot, “Gone for Goode”? Enough, apparently; after all, I did stick with the show after watching the pilot. It’s a pilot that, in its 40-minute-plus running time, contained a lot of what the entire series run would exhibit: an opener that sets the tone for the episodes and story arcs to follow.

The first scene shows two detective partners out at night at a murder scene, canvassing the area. They are the black Meldrick Lewis (Clark Johnson) and the white Steve Crosetti, (Jon Polito). They banter as they do their work, and it doesn’t take long for their jibes to turn ethnic. After Crosetti shares a piece of philosophical wisdom he says he picked up from an excerpt of a book, Lewis calls him “a little fat-head guinea, a little Italian salami brain.”

Later Detective Frank Pembleton (Braugher), who prefers to work alone, is forced to go out on a case with Detective Bo Felton (Daniel Baldwin). These two seem not to like each other much, and Pembleton, unprovoked, wastes no time in confronting Felton about his racial attitudes, saying that his own excellence as a detective is something Felton has difficulty handling. Felton, says Pembleton, resents him because to see a top-notch black detective reminds Felton that he is no better than Pembleton, and this makes Felton’s world a little less understandable. No, answers Felton; he resents Pembleton not because he’s black, but because he’s imperious and arrogant, which, in fact, he is.

At the time, it was fresh and original to see this kind of naturalistic, semi-humorous, ethnically-inflected dialogue on a cop show. It was unusual (and it happens here twice in the episode’s first twenty minutes) to see a black character laying into a white one. From the get go, Homicide made it clear that we are in an urban environment where people of every type are abrasive and idiosyncratic, though none of their individual quirks takes away from their professionalism as a group.

For the length of the series, Homicide depicted the difficulties, absurdities, and dynamic possibilities inherent in a diverse work force that has to rub shoulders every day, and the first episode contained the seeds for all this. It also established that this would not be a show dealing in anything close to stereotype. When rookie Tim Bayliss arrives at the station and asks to see Lieutenant Giardello, he is pointed toward where Crosetti and Yaphet Kotto’s character are talking. He introduces himself to Crosetti, assuming he is Giardello, but Yaphet Kotto, with a very Italian hand gesture, says to him, “Hey, I’m Giardello.” We’ll learn later in the series that Al Giardello had a Sicilian-American father and an African-American mother, and the duality of his upbringing will be reflected in his character. He speaks Italian well, loves Italian food, and is equally at ease working and spending off-duty time with white or black officers.

As for Pembleton, we see in the scene with Bo Felton that he is fiery, proud, and stubborn. That he comes from New York City and began his career there marks him as an outsider among his colleagues. We will also come to learn that he’s the most cerebral and eccentric of the detectives, a Jesuit-educated cop who knows Latin and Greek, wears ties with pink polka dots, and orders milk when he drinks in a bar.

Who can think of Homicide now without picturing the station white board on which each detective has their name written? Below that name is a list of names representing cases that detective is the primary investigator on. A case name written in red marker ink is an open case; a name in black ink is a closed case.

The first episode establishes the importance of this board and how, at times, squad members’ lives revolve around it. No cop wants to have too much red under their name, and through seven seasons, we’ll see a number of times a particular detective stands gazing at the board in satisfaction or frustration, depending on how many open cases they have.

The board can become a point of obsession for these police, and there is an existential aspect to it. Just when a detective’s name may be sitting above a list of all black names, allowing a moment of peace for the investigator, the phone rings, the detective answers, and a new case begins, going up in red under the detective’s name. Homicide used the image of the board in a way that reminded one of Camus’s “Myth of Sispyhus.” No matter how often you roll the rock up the hill, it will roll back down, signaling a return to ground zero and the need to push the rock back up. Same with the police—all police everywhere—but Homicide captured this quality better than any show I can recall, the sense of repetitive absurdity behind the job’s seriousness.

Then there’s The Box. This is the squad’s interrogation room, and in the series opener, a scene unfolds in which Pembleton and Bayliss—partnered up for the first time—question a murder suspect. Is it an interrogation, though? As Pembleton tells Bayliss before they enter the room to talk to the man in custody, “What you will be privy to witness will not be an interrogation, but an act of salesmanship … but what I am selling is a long prison term to a client who has no genuine use for the product.”

Inside The Box, Pembleton proceeds to berate, cajole, and finally break down the suspect, essentially tricking him into confessing to the killing after the man comes right up to the edge of asking for a lawyer. When he and Bayliss exit The Box, Bayliss is appalled that Pembleton cut the man off when he was on the verge of requesting an attorney, but Pembleton brushes him off with a brutally realistic rebuttal that puts what they just did into perspective. It’s a strong scene, fiercely acted, and it led to a later episode the first season, “Three Men and Adena.” Episode one director Barry Levinson liked the Pembleton-Bayliss Box scene so much, he said a whole episode could be filmed around an interrogation, and that’s what happened in the fifth episode, written by Tom Fontana.

Pembleton and Bayliss bring in an old street merchant (Moses Gunn) who they suspect has killed 11-year-old Adena Watson. We saw her body at the end of episode one, and her death becomes the first case Bayliss takes as primary.

Through several episodes, he puts everything he has into solving the case. For almost all of episode five, he and Pembleton go at it, trying to break down the old man. But as close as they appear to come to getting a confession, they never do. Tired and angry after their marathon stint in The Box, they have to let the man go. It seems that he probably was the murderer, but even to the audience, there is not one hundred-percent certainty about this. Bayliss isn’t sure anymore whether the old man killed the girl, but Pembleton thinks he did do it.

Despite their failure, something constructive results from the questioning: Pembleton voices a respect for Bayliss he hasn’t had until now. From this point on, their partnership becomes a complex and fascinating component of the series, and the episode let audiences know that not all cases would get solved. As in real life, not all stories on Homicide would end tidily. But as the show’s creators said, Homicide’s fictional murder of an 11-year-old girl was based on the real killing of a girl that age, and they felt “it would be a disservice to the real girl to have this fake TV solution.”

Homicide had a distinctive look for seven years, and episode one had that look in spades. Handheld cameras ceaselessly moving create an ambiance of life captured on the fly. There is nothing stagy in the actors’ movements; you frequently get the feeling that the cameras are trying to keep up with people as they talk, hurry to and from crime scenes, and rush to pick up phones. Color is muted, and the TV frame often teems with movement.

The jump cut was something rarely used in television then—typical were match cuts for maximum smoothness and flow—but Homicide employed it as a regular device. Jean Luc Godard’s film Breathless (1960), with all its jump cuts, served as an inspiration for the show’s editing, and from the initial episode, Homicide used this technique to keep viewers alert and off balance. The discontinuities add a bracing stylization to the realistic aesthetic, and this tension—between naturalism and an intense, slightly heightened reality—lasted until the series ended.

Baltimore’s first great crime show—that was Homicide. And as with David Simon’s The Wire, the city itself functioned as a character. Filmed on location from its beginning, Homicide announced itself as something different, not a New York City or LA cop show, and I remember the excitement I felt watching the first episode. Here was an energetic show committed to moving around a city I didn’t know well and that had a unique personality. By the time the show concluded, I felt like I knew Baltimore (as much as one can through a show) and had added it to my mental list of great crime fiction cities.

I’m happy that Homicide got a seven-year run after that first night and that I was there from the start, sucked in by the promos during the Super Bowl. For once, a network promoting its own product had something worthwhile to peddle.

1 comment:

You know, I never watched the television show, but I can attest that the book that inspired it (nonfiction), Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets by David Simon, held me rapt in can't-put-it-down fashion like few other nonfiction books ever have. Highly, highly recommended.

Post a Comment