I read a lot of crime novels, and when I'm not reading crime novels I'm often reading horror novels, so violence, whether of the physical, emotional, or spiritual varieties, is nothing new to me.

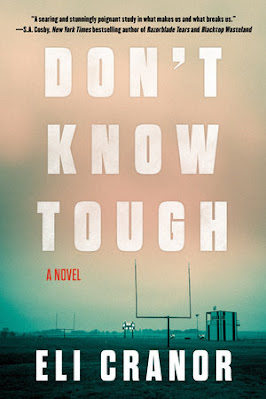

My reason for stating this up front, aside from the fact that it's true, is both to establish my bonafides, and to make you understand that when I say I had to put Eli Cranor's debut Don't Know Tough down and walk away from it, that I was actively nervous to pick it back up again, that it took me almost a week to come back to the book because I was so nervous about what would happen next, I'm being serious.

Don't Know Tough is, mostly, the story of Billy Lowe, a hard as nails running back with anger issues. his fucked up family, and the (less obviously, but still fucked up),family that takes him, in as Billy and his coach / wannabe mentor take a run at the Arkansas State Football Championships, all while under the shadow of Billy's mysteriously murdered kinda step dad.

It's a lot, but Cranor moves between characters and their distinct point of views by establishing both a linguistic rhythm to Billy's chapters, evoking the hills and poverty thats all he's ever known, and a more straightforward (though occasionally withholding) presentation when switching to other characters points of view, ensuring momentum, and, most importantly, providing the reader with information only available to those characters at the time.

To say I loved this book would be an understatement, and judging by the awards it has been received or nominated for, I'm not alone in my assessment of it, but, for me, the most memorable moment is not at the climax of the novel, and it has nothing to do with the mystery; it has to do with two characters, one who should know better, and one who has no idea, in a place of such sheer vulnerability from so many disparate elements that I actually started to sweat while reading it.

Eventually, I broke through my fear and picked the book up again, and, while I'm not going to comment on whether or not my fears came to pass, my reaction to that scene was so intense, instead of continuing on, I went back and reread the chapter that had so made my skin crawl, not for any kind of enjoyment, but to ask myself, how did he do it?

Today, we're gonna get in to that below as we break down how Cranor constructed doom.

Spoilers for Don't Know Tough ahead.

Seriously. Don't read on if you haven't read this novel.

Okay, so you too have read the book, and you're wondering what the scene is, right?

It was Lorna. Specifically, Lorna after her swim with Billy, their confrontation with the drunk members of the football team, and her fall.

I was stunned by this section. Afraid. Genuine fear. But when I went back, I could see the work Cranor had put in to elicit that exact reaction. It's a masterclass in writing. And I want to break it down:

When Lorna and Billy arrive above the river, a raging bonfire burning below them while drunk teens celebrate their Playoff win in language that evokes the bacchanalistic suggestion of hell and violence and fear that, the novel subliminally suggests, is almost certain to come:

Everybody come to the river after a game. Saw them when we drove up, whole bunch of them good and drunk already. Big bonfire tearing at the low branches, lighting they drunk smiling faces.

Next is location, the bluffs over the river, an area Billy knows, but that Lorna, new to town and unfamiliar with the area, is significantly less aware of:

Bluffs big and high this far upstream. Probably twenty, maybe thirty feet. So we cain't get in the water, not unless we jump. I jumped before. Everybody jump from the bluffs. But not in the night. Even with a full moon, you be stupid to jump at night.

The scene continues with Billy remembering another female character "in broken bits and pieces", and the death shadow grows again a page later when Billy and Lorna discuss Hemingway:

"Who is he?"

"Who?"

"Hemingway."

"You mean, who was he," she say. "He's dead. Blew his head off with a shotgun."

"A shotgun?"

"Yeah, pulled the trigger with his big toe."

This violent imagery, a head blown apart, stands in contrast to what happens next, as Billy and Lorna continue discussing The Old Man and the Sea, with the following section quoted in the book:

...and if she did wild or wicked things it was because she could not help them. The moon affects her as it does a woman.

And then Lorna, possibly moved by the moon, removes her clothes and goes to the edge of the bluff, preparing to jump in to the river, but as she jumps Billy sees, "Look like the moon went just behind a cloud and took her shadow with it".

But, though she lands in the water safely, another subconscious clue has been planted. Lorna is in the water now, and the moon also effects water. Mostly in tides, but when you're in the water, what's the difference between a tide and a current?

Safely in the water, unharmed (this time)Lorna calls from below, reminiscent of an unknowing siren:

There aint nothing good come from me jumping in that water. I jumped enough to know you got to know where you jumping, know whats below you, to even jump at all.

"The moon, Billy, can't you feel its pull?"

Billy, spurred on, prepares to jump, but death visits him again before he can, a death Billy may very well be involved in.

And theres just enough light from the moon to see what I need to see. Get my shorts and shirt off, and then a breeze blow in, cool, like it carry something with it. Kinda stink like chickens, like it connected to something way back in town.

Cranor doesn't describe the smell any further, but we can assume what Billy is smelling is HIM, Billy's sort of step-dad, dead on the floor of their trailer. Death is all around. And then he jumps

The next chapter is from Lorna's father's POV, and while it ratchets up the tension in different ways, Cranor uses separate techniques that add a different pile of compounding dread as Coach Taylor realizes that both his daughter and the violent troublemaker he has let in to his house are both missing. But after the preceding chapter, and through Coach Taylor's characterization, we know that the wrath of an angry father is not what is putting these characters in danger. It is something else, something much more base and primitive. And they are very fucking much in danger.

Returning to Lorna and Billy, we find them in the river, naked, incredibly vulnerable, and again surrounded by the language of death: "Dad will kill me," Lorna says when she notices her earring is missing as the two float downstream in the black water. Billy dives under to search for it, but "water black and taste like dirt," evoking the grave.

And then, having floated too far downstream, they arrive back at the bacchanalian fire, evocative of Dante's hell itself, the unconscious suggestion that this is all a continuously repeating and inescapable loop, traversed only by the dead or the damned. And Billy, aware of their location, Lorna unaware, voices another issue:

"We all the way back down to the bonfire."

"So?"

"The dam come after the bonfire. And the dam as far downstream as we can go. We float over that dam and we wont't be floating no more."

Lorna opts to get out of the river, naked (vulnerable) and try to skirt past the hellish bonfire, but Billy cautions her. To get past, they'll have to sneak, naked, up the bluff, suggesting another image of falling.

"Well," she say, not even whispering, (another increase in tension as the bonfire and the hellish revelers are so close by) If it's between falling to my death (that imagery again) over that dam or being seen naked-I'll take the latter."

But they're spotted, Lorna twenty feet above Billy on their climb up the bank:

I know they coming through the woods, a whole mess a them, drunk as shit and rowdy. The whole lunch table stomping through the tree line.

"Lorna," I say. "Listen, this ain't California."

"Oh my god," she say. "here we go again, another-"

"Ever one a those boys got a gun, a knife. Something. They drunk as hell and now they hearing sounds in the woods. them boys dream of this, being cowboys and shooting bad guys."

She go quiet. The moon bright enough I can see her eyes on me...

Again, Cranor is establishing that Lorna is geographically and culturally unaware of the danger they are in, while subtly injecting Hell and the moon and the woods and contrasting them with a naked young woman. Through word choice, repetition, and he has conjured an impossible mix of dreadful outcomes. The water below may carry them to the dam and death, pulled by the moon. And thats if someone survives the fall. The land is no safer, having been converted to Hell, filled with bloodlusting, and just plain lusting, drunk young men, armed to the teeth. And the scent, literally, of death is on the wind.

Hiding under the bank, Billy and Lorna both feel dirt fall on their head, once again evoking both the grave and the scattering of dirt at the culmination of funeral rites. Seeing only one way out, Lorna climbs up on the bank and confronts the men, believing, incorrectly, that, because they play for her father's football team, she'll be safe. But after acknowledging the presence of a shotgun that Billy can't see (the same kind of gun Hemingway blew his skull off with) and then, again, because of cultural confusion, goading them, Lorna is backed up to the edge. Overhearing one of the men imply rape, Billy reaches up and touches Lorna's foot, but at that moment, she slips:

I reach up. Just gonna touch her ankle. Let her know I'm here and I'm a man's man, like Hemingway. When my fingers tap her ankle she jerk back, like she forgot I's there, toes clawing at the dirt bank, hands slipping at the sky, trying to keep her balance. And then there's only Jarred standing on the ledge, laughing, as Lorna fall down the bluff towards the river and into the moon.

Look at that again. Hemingway. Dirt. Ledge. Laughing. Down the bluff. Towards the River. Into the Moon. This is life under a death cloud, and, as the chapter ends, we assume at least one, if not both Lorna and Bill are dead, not because anything in the plot us telling us that, in fact, the plot is suggesting at least one of them will be okay, but because of the way Cranor has full on ripped open your skull and whispered to you that doom is in the air.

In The Best American Noir of the Century, Ellroy wrote, "The overarching joy and lasting appeal of noir is that it makes doom fun," but these preceding chapters have been anything but fun. They're dripping with tension, each layer applied almost unnoticed until its something too big to ignore, an impossible weight on the chest. It hurts, and it hurts all the more because, the first time through, you don't even realize Cranor is doing it. Until it arrives. Until you get that horrifying titillation the best noir offers. Until you get what you, the person who opened up a crime novel, get what you goddamn came for.

Don't Know Tough is a wonderful novel, and there are other scenes I could break down where Cranor uses similar techniques, but this is the one that landed heaviest on me. If you're a writer, either accomplished or just starting out, I genuinely believe that studying these chapters will either grant new skills or further sharpen old ones. And if you've, for some reason, read all the way down here without owning the book, your own copy that you can mark up, hey, check that out, the hardcover is on sale on Amazon right now. Just eight bucks.

Okay. That's it for me for now. I'll be back in a week or two. I can't promise I'll be talking about anything lighter, but, you know, there's always hope. Until there isn't.