A few weeks ago, after I was part of a discussion on Facebook about Robert Altman's film version of The Long Goodbye (1973), which remains remarkably divisive among crime fiction people after all these years, I decided to watch, for the fourth or fifth time, the private eye movie Altman produced a few years after his irreverent Chandler adaptation, The Late Show (1977). I wrote a piece about this film several years ago, and I thought it would be no shame after these many years to post it again here. After all, while Robert Benton wrote and directed The Late Show, it does have Altman's creative input. It makes for a good companion piece to the earlier film, the second half of a distinctive 70s PI double bill. The films have similarities but at the same time are quite different. Anyhow, here's the piece.

Familiar Yet Foreign Noir: The Late Show

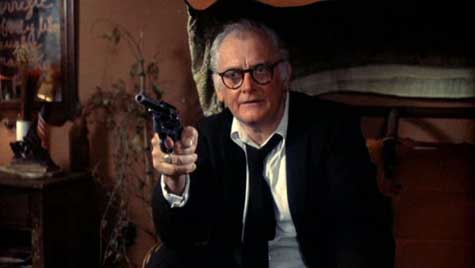

The plot kicks off fast. A moment after we first see Ira Wells (Carney) sitting in his recliner, his land-lady Mrs. Schmidt says that he has a guest. So late at night? The man there to see him opens his mouth to say Ira’s name and blood comes out. He’s been shot point blank in the stomach. It’s clear the man, about Ira’s age, is a former partner of Ira’s, and Robert Benton has some cultural reference fun here also: this man, named Harry, is the veteran actor Howard Duff, radio’s Sam Spade from 1946 to 1950. I first saw The Late Show when it opened, at age 15, and even though I had no idea who Duff was, my parents instantly recognized him and chuckled, getting the joke. In any event, the former tough guy dies in Ira’s room, but not before giving Ira information that will be of great importance later. At Harry’s funeral, an old friend of them both named Charlie (Bill Macy) introduces Ira to Margot, an oddball, 70’s style New Age woman played by Lily Tomlin. A male acquaintance of Margot’s has taken her cat because Margot owes him money, and Charlie has touted Ira as just the guy, a total pro, who can track down her acquaintance and get her cat back. Ira scoffs at the “two bit job” offered, but when he finds out more about the case, and how it ties in to Harry’s death, he says he’ll take it. Not that Margot is impressed. Besides his gut, Ira has a slight limp, a hearing aid, and a crotchety personality that shows no respect for the young. Margot voices her doubts about Ira, but Charlie, who oozes two-bit chiseler through his every pore, reassures her. Ira may not look like much, but he’s been around and you’re not going to find a better gumshoe. Still, taking him on will cost her. He’s no amateur. As Ira tells her, “I’m the best and I get paid like the best.” Oddly, it’s this assertion of his prowess that sways Margo, and she hires him.

From here, of course, the story expands. The dangers increase. Unsavory characters appear, and so do dead bodies. Ira takes a beating and dishes one out, gets shot at and fires back. He and Margot become a team, sort of, and she is the one who does the driving during the exciting car chase they have. They encounter a long-legged sultry woman (Joanna Cassidy) who seems to fit the femme fatale bill, and the case they investigate becomes increasingly complicated before they can resolve it. Complicated, but not incoherent: The Late Show’s solution makes perfect sense, and Benton even manages, in golden-age mystery fashion, to get all the participants in one room when Ira gives them (and the audience) the lowdown.

The Late Show was Robert Benton’s second directorial effort, following up on his 1972 revisionist western Bad Company. He had been writing in Hollywood for years, contributing to Peter Bogdanovich’s What’s Up Doc script, and, most famously, co-writing with David Newman the script for Bonnie and Clyde. Like many filmmakers of his era, Benton was influenced by the French New Wave of Jean Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut. He admired how their films often mucked around with genres, how they blended familiar styles and tropes to fashion something new. He had a big part in creating the mix of violence and jokiness that made Bonnie and Clyde so unusual, and disturbing when it premiered, and he carried this aesthetic through to The Late Show. Giving the audience an indication (or warning?) of what they were in for, the movie’s advertising tagline perhaps summed up best the script’s tonal variety: “The nicest, warmest, funniest, and most touching movie you'll ever see about blackmail, mystery, and murder.” It’s an accurate tagline. And perhaps it was this unpredictable quality that appealed to filmmaker Robert Altman, ever the maverick. Benton brought his completed script to Altman, and Altman, who had Hollywood clout at the time, liked what he saw and decided to produce the movie.

It’s fascinating to compare The Late Show with Altman’s The Long Goodbye. There’s an odd continuity between the two, and one wonders what Benton and Altman discussed regarding this. Both films have a grainy, washed-out look that hearkens back to an earlier era. In each, the detective regularly wears a dark suit, white shirt, and tie, while nearly everyone else dresses in the slick or colorful or billowy clothes of the time. The two films share an editor, Lou Lombardo, who worked several times with Altman, (Peter Appleton co-edited The Late Show), and both clearly function as ironic homages to private eye tales, California ones especially. And yet, despite their points of connection, the two are utterly different films. Elliot Gould’s Rip van Marlowe (as Altman called him) is a deliberately anachronistic stranger in a strange 1970s Los Angeles. He’s not an old man compared to the characters he moves among, but his entire world and moral view stamp him as out of touch, disconnected from his time. Little upsets him much; his position as a character out of time serves as an emotional armor. Ira Wells, by contrast, is an old man, so he’s a person who’s seen the world change around him. He has none of the Gould as Marlowe detachment, and part of what makes his character compelling is his emotional richness. He’s got the requisite toughness to be a PI, but we also see a person who is by turns aloof, protective, caustic, vulnerable. In his profession, his age and physical state are a liability, but then again, the experience he’s acquired down through the years is a plus. He seems at once a bit lost in modern Los Angeles – his investigation to find Margo’s cat starts terribly and he has no idea that an old police contact of his has died – and at home everywhere in the city. He may get tired and cranky easily, but he’s seen everything in his time and nothing that happens on the case, no type of human behavior, rattles him. By the end, he’s even gained Margot’s respect.

It is the relationship between Wells and Margot that makes up the heart of the film. As people, they differ in every conceivable way. They represent different generations, and while his lingo stems from the 1940s, she talks of “going with the flow”, her own “conflicted personality”, and people being “de-evolved.” When under stress, he smokes cigarettes or takes Alka-Seltzer tablets; she curls into a meditative pose and says “Om.” If Margot smokes anything, it’s marijuana, a substance she happens to sell sometimes. Margot is no airhead, though, and it’s telling that she, not Ira, has the first substantial insight into the case that provides them with a crucial lead. Ira, surprised, admits that she may have something. And Margo, in her way, is as nonsense-free as Wells. When he says he has to find the guy who nailed Harry Regan, sounding like Sam Spade talking about the need for a man to avenge the killing of his partner, Margo tells him that is bullshit. “It’s disgusting,” she says. He doesn’t care about Harry Regan but wants one last chance to go around shooting guns at people playing cops and robbers. “You’re getting off behind all this blood and guts,” she says. “It’s very immature. You need help.” But what begins as a testy relationship between an old-school guy and a macho code-critiquing 70’s woman develops into something else, and the audience enjoys this aspect of the story as much as the mystery plot. Restrained but real affection grows between the two but without the clichés of movie romance. We don’t get the familiar Hollywood nonsense of a younger woman falling for an older guy. They are just two people struggling to make do, who somehow, through unlikely circumstances, find themselves simpatico.

As the two leads, Art Carney and Lily Tomlin shine. In the wake of his long run on The Honeymooners, Carney was enjoying a strong film career during the 70’s. In 1974, he had won a Best Actor Oscar for his role as an old man driving across country with his cat in Harry and Tonto. The Late Show followed on the heels of that performance, and if you ask me, he’s better in Benton’s film than in his award-winning one. Lily Tomlin’s unique talent has never been better utilized on film, and the word is that Benton and Altman (Tomlin was an Altman favorite for his entire career) encouraged her to improvise. At first, this bothered Carney, who liked to work by following the lines exactly as written in the script. But eventually, with the Benton’s urging, he began to improvise with her, and the two meshed. You’d be hard put to find another film where two actors of different generations, different sensibilities and acting styles, have such good chemistry.

Among the supporting actors, Bill Macy was then starring as Bea Arthur’s long suffering husband in the sitcom Maude, so it was striking for audiences to see him as a slimy conniver. Eugene Roche and John Considine are both funny and menacing as the fence Birdwell and his muscleman Lamar, and Ruth Nelson brings the requisite steely sweetness to her role as Ira Wells’ land-lady Mrs. Schmidt. An interesting note about Nelson: she had been working in Hollywood since the 1940s but before that, in New York, she was a founding member of the legendary Group Theater. The Late Show is a film with a small cast, but every performer in it brings life, wit, and texture to their part.

When released, The Late Show got positive reviews everywhere. It wound up getting film critic awards and an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay. Benton won an Edgar for his script. But for whatever reason, Warner Brothers didn’t promote the film much, and the movie came and went in theaters without making a splash. A sequel Benton had in mind, in which Wells and Margot form the detective team she has discussed, never came to fruition. That’s a pity. So is the relative underappreciation the film has suffered. But it exists now on streaming services and home video, easily accessible, a private eye film all fans of the genre should check out.

No comments:

Post a Comment