By

Scott D. Parker

Almost from the day it was announced, I knew I wanted to read THE PRESIDENT IS MISSING by Bill Clinton and James Patterson. On the one hand you have one of the all-time best-selling authors who has created his own fiction factory. On the other, you have a former president who served for eight years in the office and could provide vital details as only a man who sat in the Oval Office could. It was a match made in heaven.

But would the book be any good?

It’s an honest question, but let’s be honest: if it’s got Patterson’s name on it, the story will at least be serviceable.

And I’m here to tell you it’s more than serviceable. It’s pretty darn good.

The story opens as President Jonathan Lincoln Duncan, newly widowed, is facing the prospect of a compelled testimony in front of a Congressional committee. Impeachment is in the air because Duncan recently ordered a special forces raid seemingly to save notorious terrorist Suliman Cindoruk, leader of the Sons of Jihad group. The Speaker of the House—a member of the unnamed ‘other party’; Duncan’s party affiliation also remains unnamed making it more bipartisan—who has designs on the presidency smells blood.

But Duncan has an even greater problem. Somehow, Suliman’s cyber hackers have implanted a virus in the computer systems of the Pentagon. Codenamed “Dark Ages,” if released, the resulting damage would be catastrophic. It would literally plunge the US into a modern dark ages. And one of six members of Duncan’s inner circle—including the Vice President—is a traitor because a young girl from the Republic of Georgia is asking to meet with Duncan. Alone. And she utters “Dark Ages” to prove her point.

How could this young woman know that? Who is she? And, after Duncan goes incognito and meets at the baseball stadium, who is this other guy pointing a gun at the President of the United States?

THE PRESIDENT IS MISSING clocks in at over 500 pages, but they read extremely fast. Duncan’s prose is all in first person and the entire novel is written in the present tense, giving it an urgency. Having Duncan narrate his own scenes is great, especially with his asides when he gives details you know came from Bill Clinton’s memories. There are other characters and all those scenes are related in third person. It’s the first time I can remember reading a book like this. Granted, as a writer, I noticed the differences at first, but as the story went on and my reading speed increased, it faded away and I was solely in the action.

By now, Patterson is a master at crafting a story and, while I’ve read few, I could see how one of his stories is made. And I really loved how the tension was racketed up. Sure, there were lots of cliffhanger chapter endings, but this is a summer thriller. It’s supposed to have cliffhangers.

And there was one passage of about five chapters that completely fooled me. I thought one thing was happening and it was something else entirely. Much like watching “The Sixth Sense” a second time when you know the truth, I re-read those chapters just to see how Patterson did it. Brilliant. Also brilliant was the skillful way Patterson kept the truth behind the traitor and other characters, revealing their identity at precisely the right time. This guy can tell stories!

I purchased this book from my local grocery store and I pointed out something to some friends who noticed the book in my basket. I indicated all the other Patterson novels on display—eight?—and then at THE PRESIDENT IS MISSING. Patterson’s name was listed on top of all save the new one. It takes a president’s name to shift Patterson to second billing.

I very much enjoyed this book and would easily recommend it as a good beach read.

Saturday, June 30, 2018

Friday, June 29, 2018

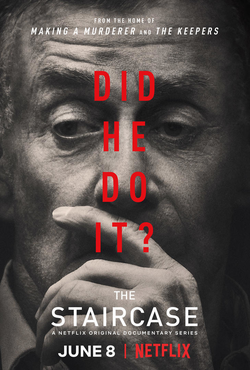

The Staircase, and the perils of being strange

Who else has been watching The Staircase?

Prepping for a recent trip, I had the TV on a lot while I tried to get ahead of all my chores. I watched several episodes of Confession Tapes and binged almost all of The Staircase, both available on Netflix. Both send a shiver down the spine, The Staircase especially, because they both show how bias and not fitting in can ruin a person’s life.

(Major spoilers for The Staircase follow).

The Staircase follows the trial of author, Michael Peterson, accused of murdering his wife, Kathleen. It’s a weird case. Nothing about Kathleen’s death makes sense - whether it’s viewed from the POV of a murder or an accident - and so the preparation for, and duration of, the trial was often shocking and baffling. What’s kept me up at night, and kept me from finishing the last two episodes or looking for spoilers on Peterson’s retrial, though, isn’t lingering questions about whether he did it, or if it was a murder at all. Instead, what left me with a knot in my stomach was the fact that the police and prosecution flaunted using biphobia and Peterson’s allegedly open marriage as evidence in their case.

The viewer has no idea if Peterson is telling the truth when he says his wife knew about his dalliances with men. Most people, if told the police are using “his wife discovered his bisexuality and affairs” as a motive for murder, would say “Oh, she knew, she knew!” But what’s scary is that no one ever considered - even for a moment - that it could be true. Even Peterson’s defense attorney, when cross-examining Peterson’s sister in law, who believed his innocence right up until the prosecution told her about gay porn, bothered to raise the possibility that Peterson and his wife had a non traditional marriage. The prosecution brought up a male escort (who notably didn’t sleep with Peterson) to question him about his pornographic photos and sexual conversations with Peterson, but then turns to the jury and pretends that Peterson’s interest in men is literally unspeakable. They can show gay porn for shock value in court, but in closing statements it has to be spoken about as though it was kiddie porn.

The persistent biphobia and rejection of the mere possibility that sometimes wealthy white men with wives they love very much go have sex with men (I mean, come on, we know this happens!) work for the prosecution in ways one would think impossible as recently as 2001. That would be enough to make me uncomfortable. But what threw me, made it impossible for me to worry over whether Peterson was guilty, innocent, or even a nice person, was when the documentary showed his former sisters-in-law going through his writing, digging up short stories, and reading his (fictional) accounts of death and murder. They read it out loud like it was a salacious confession, almost giddy in “proving” he was fucked up. One repeated over and over again “he knew something was wrong with him, this was him trying to figure it out.” They thought the first person stories, in particular, made it clear that Peterson was a born and bred murderer.

The stories didn’t make it into evidence, but it’s implied that they would have, had Peterson taken the stand. The prosecution couldn’t read his fiction and imply it was reality, so instead they leaned heavily on emphasizing that Peterson is a “fiction writer”, a phrase repeated several times in closing. The implication is clear - he lies for a living, he knows how to tell a story, so you can’t trust him. And even if you could, a guy who looks at gay sailor porn couldn’t love his wife anyway.

As a bunch of crime writers pushing the envelope and trying to look at the darkest parts of our world - this should scare the shit out of us. How could a fictional character murdering another fictional character even be considered evidence that a real life person murdered their real life spouse? When combined with the emphasis on Peterson’s sexuality and (maybe) open marriage, the message is clear: Don’t be a fucking weirdo, or you’re done for.

I find it hard to collect my thoughts on an author who wrote about war (which is often times uglier than crime) from the perspective of a veteran having his fiction held over his head like a guillotine, especially alongside hyper-phobia of bisexual men and non-traditional marriages. It’s too much to unpack. The lawyer, Rudolph, often seems as overwhelmed. At points I can’t tell if he is convinced of his client’s innocence, or convinced of his guilt, but baffled by how the trial is playing out.

I don’t have a nice bow to tie this all up in, as of now I don’t even know Peterson’s fate. But it would be nice to think that being a creative wouldn’t be evidence against you in a jury trial. Or that what kind of porn you watch, or the boundaries you set with your consenting spouse wouldn’t be aired out to strangers to prove what a deviant person you are. The irony is, it’s probably on the creatives to change public perceptions, so that people who write about bad stuff, or people who don’t fit neatly into the straight-monogamous-Christian and white box don’t have to worry that being themselves puts them in danger of anything from losing a job, to life in prison.

So I guess we’d better get to work.

Prepping for a recent trip, I had the TV on a lot while I tried to get ahead of all my chores. I watched several episodes of Confession Tapes and binged almost all of The Staircase, both available on Netflix. Both send a shiver down the spine, The Staircase especially, because they both show how bias and not fitting in can ruin a person’s life.

(Major spoilers for The Staircase follow).

The Staircase follows the trial of author, Michael Peterson, accused of murdering his wife, Kathleen. It’s a weird case. Nothing about Kathleen’s death makes sense - whether it’s viewed from the POV of a murder or an accident - and so the preparation for, and duration of, the trial was often shocking and baffling. What’s kept me up at night, and kept me from finishing the last two episodes or looking for spoilers on Peterson’s retrial, though, isn’t lingering questions about whether he did it, or if it was a murder at all. Instead, what left me with a knot in my stomach was the fact that the police and prosecution flaunted using biphobia and Peterson’s allegedly open marriage as evidence in their case.

The viewer has no idea if Peterson is telling the truth when he says his wife knew about his dalliances with men. Most people, if told the police are using “his wife discovered his bisexuality and affairs” as a motive for murder, would say “Oh, she knew, she knew!” But what’s scary is that no one ever considered - even for a moment - that it could be true. Even Peterson’s defense attorney, when cross-examining Peterson’s sister in law, who believed his innocence right up until the prosecution told her about gay porn, bothered to raise the possibility that Peterson and his wife had a non traditional marriage. The prosecution brought up a male escort (who notably didn’t sleep with Peterson) to question him about his pornographic photos and sexual conversations with Peterson, but then turns to the jury and pretends that Peterson’s interest in men is literally unspeakable. They can show gay porn for shock value in court, but in closing statements it has to be spoken about as though it was kiddie porn.

The persistent biphobia and rejection of the mere possibility that sometimes wealthy white men with wives they love very much go have sex with men (I mean, come on, we know this happens!) work for the prosecution in ways one would think impossible as recently as 2001. That would be enough to make me uncomfortable. But what threw me, made it impossible for me to worry over whether Peterson was guilty, innocent, or even a nice person, was when the documentary showed his former sisters-in-law going through his writing, digging up short stories, and reading his (fictional) accounts of death and murder. They read it out loud like it was a salacious confession, almost giddy in “proving” he was fucked up. One repeated over and over again “he knew something was wrong with him, this was him trying to figure it out.” They thought the first person stories, in particular, made it clear that Peterson was a born and bred murderer.

The stories didn’t make it into evidence, but it’s implied that they would have, had Peterson taken the stand. The prosecution couldn’t read his fiction and imply it was reality, so instead they leaned heavily on emphasizing that Peterson is a “fiction writer”, a phrase repeated several times in closing. The implication is clear - he lies for a living, he knows how to tell a story, so you can’t trust him. And even if you could, a guy who looks at gay sailor porn couldn’t love his wife anyway.

As a bunch of crime writers pushing the envelope and trying to look at the darkest parts of our world - this should scare the shit out of us. How could a fictional character murdering another fictional character even be considered evidence that a real life person murdered their real life spouse? When combined with the emphasis on Peterson’s sexuality and (maybe) open marriage, the message is clear: Don’t be a fucking weirdo, or you’re done for.

I find it hard to collect my thoughts on an author who wrote about war (which is often times uglier than crime) from the perspective of a veteran having his fiction held over his head like a guillotine, especially alongside hyper-phobia of bisexual men and non-traditional marriages. It’s too much to unpack. The lawyer, Rudolph, often seems as overwhelmed. At points I can’t tell if he is convinced of his client’s innocence, or convinced of his guilt, but baffled by how the trial is playing out.

I don’t have a nice bow to tie this all up in, as of now I don’t even know Peterson’s fate. But it would be nice to think that being a creative wouldn’t be evidence against you in a jury trial. Or that what kind of porn you watch, or the boundaries you set with your consenting spouse wouldn’t be aired out to strangers to prove what a deviant person you are. The irony is, it’s probably on the creatives to change public perceptions, so that people who write about bad stuff, or people who don’t fit neatly into the straight-monogamous-Christian and white box don’t have to worry that being themselves puts them in danger of anything from losing a job, to life in prison.

So I guess we’d better get to work.

Thursday, June 28, 2018

We're Not Going To Do Anything Stupid, Are We?

I had the opportunity to listen to a few of the episodes of Eryk Pruitt's true crime podcast The Long Dance and it's quite good, better than many of its brethren. All of its episodes drop on July 3rd. You may remember I wrote about The Long Dance back in January after sharing some barbecue with Eryk. So I thought I invite Eryk to stop today by and tell us a little story about the making of the podcast. I hadn't expected this. – David Nemeth

By Eryk Pruitt

For my work writing and producing The Long Dance, the eight-part true crime podcast detailing the North Carolina Valentine’s Murders, I had to step far outside my own comfort zone. Far from my darkened work cabin, the research required me and my partner, investigative reporter Drew Adamek, to criss-cross the state of North Carolina in search of interview subjects who would inform the audio documentary we constructed to tell the story of the investigation into who killed Patricia Mann and Jesse McBane in February, 1971. Since this was not a requirement for fiction writing, I suffered a bit of a learning curve.

For example, I never fancied myself a great interviewer before we started work on this project, back in the Fall of 2016. As I learned with my short-lived radio show, The Crime Scene with Eryk Pruitt, I tended to bulk up on research, then interviewed on behalf of a well-researched host. Instead, I should have asked the questions the audience wanted to know. Lucky for me, Adamek was a skilled interviewer and allowed me to learn by watching him at his craft.

Adamek taught me to warm up the subject, rather than dive immediately into the more difficult details. When interviewing family and friends of Pat and Jesse, Adamek would sometimes not even get to the details of the disappearance until we’d been talking to them for over an hour. Also, my tendencies would be to take my heavy research into the interview to seek out a narrative that I had preconceived. This, also, was a mistake. A more relaxed, natural interview led us to some very unexpected places.

Speaking of unexpected, we learned quickly to be prepared for it. Often, there was no way to predict what would happen when we knocked on a door, or met someone in a neutral location. Once, an interview subject’s wife suffered a heart attack in the middle of our session. We waited with our subject while the paramedics arrived and loaded her into the ambulance. Another time, we revealed to a subject that his father had passed away eight years earlier. He had spent the majority of his life searching for the man, and had no idea. In another instance, we dropped in on the man who investigators believe to be the primary suspect. The man has a record of extreme violence, is known to carry a firearm, and has an irrational temper. In this instance, we used hidden microphones and a clandestine go-pro camera. We also had a production team in a van outside his doctor’s office…

But it was one particular interview in Greensboro that left the biggest mark. One man held a key, damning piece of information and, without it, we could never present our case against the primary suspect. After several phone calls went ignored, Adamek and I hopped in the car and drove the hour west to Greensboro. We located his house and knocked several times until finally he answered.

He was clearly agitated, and once he discovered we wanted him to talk about a particularly troubling moment in his young life, he became more upset. He demanded we leave his property, then chased us across the yard to continue his harangue. After a bit, we talked him down and he asked us to come inside so not to disturb his neighbors. We agreed.

The first thing I noticed when we stepped inside his house was that there was very little furniture in the living room.

The second thing was the cage.

Yes, a six-foot, steel cage in the middle of the living room, across from a twin sofa set and very little else.

The next thing: The door bolting behind us.

Adamek and I had no choice but to keep cool as we walked past the cage and took our seats on the couch. The man ordered us to turn off our recorders, then proceeded to rant for thirty minutes straight about his situation back then, his situation now, and any other number of things that escape my recollection because all that was running through my mind was:

I didn’t tell my wife where I was going.

I didn’t tell anyone where I was going.

Like an idiot, I just hopped in the car and drove to Greensboro and now I’m sitting in the living room with a clearly disturbed man who KEEPS A FUCKING CAGE IN HIS HOUSE.

I calculated how much time it would take for my wife to notice me missing. How long would it take for her to call Captain Tim Horne, our liaison at the Orange County Sheriff’s Office? How long would it take for him to figure out where we had gone?

How long would we spend together in that cage?

Lucky for us, it never came to that. Our subject calmed down and permitted us to record his version of the events. We exchanged email addresses and phone numbers. After Adamek and I left the property, neither one of us were able to speak until we were miles down I-40.

Which brings me to the final, and perhaps most important lesson I learned as I sharpened the new skill of interviewing for research:

When conducting interviews during a murder investigation, always tell someone where you are going.

You may need an extraction plan.

All eight episodes of THE LONG DANCE will be released on July 3. You can find us at www.thelongdancepodcast.com, on iTunes, Stitcher, iHeartRadio, and wherever you find your favorite podcasts. Our Instagram page has photographic media related to the case. Thank you for listening!!

By Eryk Pruitt

For my work writing and producing The Long Dance, the eight-part true crime podcast detailing the North Carolina Valentine’s Murders, I had to step far outside my own comfort zone. Far from my darkened work cabin, the research required me and my partner, investigative reporter Drew Adamek, to criss-cross the state of North Carolina in search of interview subjects who would inform the audio documentary we constructed to tell the story of the investigation into who killed Patricia Mann and Jesse McBane in February, 1971. Since this was not a requirement for fiction writing, I suffered a bit of a learning curve.

For example, I never fancied myself a great interviewer before we started work on this project, back in the Fall of 2016. As I learned with my short-lived radio show, The Crime Scene with Eryk Pruitt, I tended to bulk up on research, then interviewed on behalf of a well-researched host. Instead, I should have asked the questions the audience wanted to know. Lucky for me, Adamek was a skilled interviewer and allowed me to learn by watching him at his craft.

Adamek taught me to warm up the subject, rather than dive immediately into the more difficult details. When interviewing family and friends of Pat and Jesse, Adamek would sometimes not even get to the details of the disappearance until we’d been talking to them for over an hour. Also, my tendencies would be to take my heavy research into the interview to seek out a narrative that I had preconceived. This, also, was a mistake. A more relaxed, natural interview led us to some very unexpected places.

Speaking of unexpected, we learned quickly to be prepared for it. Often, there was no way to predict what would happen when we knocked on a door, or met someone in a neutral location. Once, an interview subject’s wife suffered a heart attack in the middle of our session. We waited with our subject while the paramedics arrived and loaded her into the ambulance. Another time, we revealed to a subject that his father had passed away eight years earlier. He had spent the majority of his life searching for the man, and had no idea. In another instance, we dropped in on the man who investigators believe to be the primary suspect. The man has a record of extreme violence, is known to carry a firearm, and has an irrational temper. In this instance, we used hidden microphones and a clandestine go-pro camera. We also had a production team in a van outside his doctor’s office…

But it was one particular interview in Greensboro that left the biggest mark. One man held a key, damning piece of information and, without it, we could never present our case against the primary suspect. After several phone calls went ignored, Adamek and I hopped in the car and drove the hour west to Greensboro. We located his house and knocked several times until finally he answered.

He was clearly agitated, and once he discovered we wanted him to talk about a particularly troubling moment in his young life, he became more upset. He demanded we leave his property, then chased us across the yard to continue his harangue. After a bit, we talked him down and he asked us to come inside so not to disturb his neighbors. We agreed.

The first thing I noticed when we stepped inside his house was that there was very little furniture in the living room.

The second thing was the cage.

Yes, a six-foot, steel cage in the middle of the living room, across from a twin sofa set and very little else.

The next thing: The door bolting behind us.

Adamek and I had no choice but to keep cool as we walked past the cage and took our seats on the couch. The man ordered us to turn off our recorders, then proceeded to rant for thirty minutes straight about his situation back then, his situation now, and any other number of things that escape my recollection because all that was running through my mind was:

I didn’t tell my wife where I was going.

I didn’t tell anyone where I was going.

Like an idiot, I just hopped in the car and drove to Greensboro and now I’m sitting in the living room with a clearly disturbed man who KEEPS A FUCKING CAGE IN HIS HOUSE.

I calculated how much time it would take for my wife to notice me missing. How long would it take for her to call Captain Tim Horne, our liaison at the Orange County Sheriff’s Office? How long would it take for him to figure out where we had gone?

How long would we spend together in that cage?

Lucky for us, it never came to that. Our subject calmed down and permitted us to record his version of the events. We exchanged email addresses and phone numbers. After Adamek and I left the property, neither one of us were able to speak until we were miles down I-40.

Which brings me to the final, and perhaps most important lesson I learned as I sharpened the new skill of interviewing for research:

When conducting interviews during a murder investigation, always tell someone where you are going.

You may need an extraction plan.

All eight episodes of THE LONG DANCE will be released on July 3. You can find us at www.thelongdancepodcast.com, on iTunes, Stitcher, iHeartRadio, and wherever you find your favorite podcasts. Our Instagram page has photographic media related to the case. Thank you for listening!!

Wednesday, June 27, 2018

A Guest Post by Jennifer Hillier

Welcome Jennifer Hillier to DSD- you've heard of her, because we all can't stop clamoring about how good her latest thriller Jar of Hearts is, and it lives up to the hype. (read my review at Criminal Element). I'm in Alaska probably in the process of being converted into bear scat, and Jennifer was kind enough to drop by and write about ....

The Monster in Your Neighborhood

A couple of years ago, I came across an article online about a woman named Karla Homolka. She was living in a Montreal suburb with her husband and children, and the news was reporting that Karla had recently volunteered at her kids' school in some capacity.

All in all, a pretty boring

story. Except that Karla herself isn’t boring. You see, Karla Homolka—now

Leanne Bordelais—isn't just your ordinary suburban parent. She's the former

wife of serial killer Paul Bernardo. Her testimony, in exchange for twelve

years in prison, was crucial in putting her then-husband away for life.

But she's not innocent.

Paul was convicted of raping and

murdering three young women. One of them was Karla's little sister. The other

two victims were also teenagers. And Karla participated in all of it. Paul

liked to film everything, and there is video evidence detailing all the many ways

his wife was involved. So this article—which talked about Karla raising her

children in the suburbs and doing seemingly normal "mom things"—also

highlighted the community's outrage.

It seems nobody has forgiven

her, and I doubt any of us ever will.

Paul and Karla have always

fascinated me. Growing up in the suburbs of Toronto in the 1990s, which was their

hunting ground, the crimes had a profound impact on my own teenage years. As

details seeped out during the trial (reported by the American press, as there

was a publication ban on the crimes within Canada), it seemed that everybody

knew someone who knew someone who'd been affected in some way.

"My neighbor's aunt used to

cut hair at the salon near the veterinary clinic where Karla worked," a

friend at school informed me.

"My cousin used to date a

guy who went to the same school as one of the victims. They were in the same

math class last year," someone else said.

These connections seemed forced

and silly now, but at the time, they were extremely important. It felt like we

were all a few degrees away from the horror of Paul and Karla. Monsters weren't

supposed to exist in the safe neighborhoods where we lived.

In the storybooks we read our

kids, the monsters die at the end. Or they're at least tucked away somewhere

out of sight, like Paul, where they can't hurt anybody. They're most certainly

not sitting next to you munching on a ham-and-cheese pinwheel at the Tuesday

night PTA meeting. The thought of Karla walking around like a regular person—a

mother, a wife, a neighbor, a parent volunteering at her children's school—is sickening,

and frankly, confusing. Yes, she served her sentence, but still, it doesn't

feel right.

Why does Karla get to start

over? Why gives her the right to believe she can? What degree of

compartmentalization does she have to possess to be able to build a new life

for herself on top of all the lives she's ripped apart? Is she even sorry? Does

she feel sadness? Does she ever think about the last few hours of those young

women's lives? Does she ever dream about how they died?

And if she doesn't, does that

mean she's rehabilitated and leaving her past behind . . . or does it mean that

she's still a monster? Or was she never a monster at all? Was she simply

another victim, as she proclaimed to be, of her abusive serial killer

ex-husband?

What happens to the monsters

after they're caught, put away, and then let

back out?

I had so many questions, and

writing JAR OF HEARTS seemed like the only way to answer them. I've long

believed that crime fiction provides a safe space for us to dissect and process

all of the terrible things that happen in the world, even if the endings aren't

always happy. Reading and writing crime fiction can provide deeper insight into

how minds darker than ours might work.

Because there are monsters all around us. Even in our

safe little neighborhoods.

Tuesday, June 26, 2018

Mixtapes of Murder

Scott's Note: Richie Narvaez guest blogs today, talking about something that deserves attention - the mix of crime fiction and music. It's a rich topic, so why waste time?

Take over, Richie...

Take over, Richie...

Mixtapes of Murder

by Richie Narvaez

by Richie Narvaez

The mix of crime fiction and music has been getting a lot of play recently. Several recent and upcoming anthologies partner harmony and harm, and it’s set me to thinking about how music echoes in the fiction of some of my crime-writing friends as well as my own work.

The Big Score

Publishers certainly like themes to hang books and sales on. Cats. Dogs. Cities. Holidays. Pastiche. Politics. But mostly cats and dogs. Still, there is something special about the duet of music and mystery.

Throughout history, every type of music has been vilified as Devil’s brew. “Ye troubadours maketh much evil!” “That Rudy Vallée sure is a caution!” “[Washboard players / blues singers / jazz musicians / rock stars / rappers] are in league with Satan!” Music is intimate, personal. It throbs with sex, subversion, and trouble. The beat of young love, the thrum of rebellion, the rhythm of the Other. It is the soundtrack to all our sinful thoughts, deeds, and fears, accompanying them and, according to some, even inspiring them.

So it makes sense that mystery and music tango well. Think of the appeal of murder ballads. Of the amount of violence in opera.

Consider Sherlock with his crashing violin. Traditional crime fiction certainly has an ear for classical music, perhaps because its writers had high tone tastes and/or because early crime fiction was a staunch upholder of upper class standards.

But by the mid-20th century, lonesome saxophones haunt the shadows surrounding middle-class private eyes, and later jazzy theme songs introduce such shows as Peter Gunn and 77 Sunset Strip. (Please think of the snappy theme song and not "Kookie, Kookie, Lend Me Your Comb"). I can’t think of Mike Hammer without thinking of “Harlem Nocturne.” Music is intricately linked with the genre.

Second Hearse, Same as the First

Music as a plot point for mystery stories has a long history. (For a generous list, see Josef Hoffman’s Music and Crime: 50 Novels: http://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=17669). Music-themed crime fiction anthologies go back to at least Murder to Music: Musical Mysteries from Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine and Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine (1998). In this century, there was Murder . . . and All That Jazz (2004) and then A Merry Band of Murderers: An Original Mystery Anthology of Songs and Stories (2006).

More recently — and you might sense a shift here in tastes just from the titles — we’ve had Crime Plus Music: Twenty Stories of Music-Themed Noir (2016), edited by Jim Fusilli, Waiting To Be Forgotten: Stories of Crime and Heartbreak, Inspired by The Replacements (2016), edited by Jay Stringer, and then Gutter Books’ Rock Anthologies, including Trouble in the Heartland: Crime Fiction Based on the Songs of Bruce Springsteen (2014) and Just to Watch Them Die: Crime Fiction Inspired By the Songs of Johnny Cash (2017), both edited by Joe Clifford.

In 2019, we’ll see Murder-a-Go-Go’s: Crime Fiction Inspired by the Music of the Go-Go’s, edited by Holly West, and The Hangman Isn’t Hangin’: Fiction Inspired by the Music of Steely Dan, edited by Brian Thornton.

Thornton calls these kinds of anthologies “the ultimate homage” to musicians who also happen to be great storytellers.

“And Steely Dan and crime fiction? Listen to their lyrics. So many of their songs have a potential or even outright criminal angle: ‘Kid Charlemagne,’ ‘Here at the Western World,’ ‘Sign in Stranger.’ I could go on and on.”

There’s probably more than an air of nostalgia in these collections, too, a longing for a, shall we say, more melodious time. So far, there’re no anthologies inspired by the hits of Justin Bieber, Ed Sheeran, or Rihanna. (Also: Note how most anthos so far are about male and dominant paradigm singers/bands.) But give it time.

Hitting a High C — for Crime!

Many of the stories in these anthologies contain lyrics or plot elements from the songs they’re homaging. For the Steely Dan anthology, I chose “Rikki Don’t Lose that Number” and wrote the story trying to figure out Rikki’s side of the story while referencing some of the song’s lines (without crossing into copyright infringement, I hope, I hope).

In writing that story, I realized I use music a lot as a starting point. In the recently published anthology Tiny Crimes: Very Short Tales of Mystery and Murder, edited by Lincoln Michel and Nadxieli Nieto, my story “Withhold the Dawn” was inspired by letting one word follow another as Don McLean’s “American Pie” killed me softly in the background. The song worked its way into the story, which is about a vengeful ax-wielder, not the Big Bopper, et al. But there is a loose pastry allusion.

That’s the way music is. It’s is a large part of the pop culture detritus that litters our brains. But that can be helpful when writing.

When I was invited to contribute to the upcoming The Black Car Business, Volume 2 (September 2018), edited by Larry Kelter, I was stuck on what to write. I’ve no particular passion for automobiles. So I turned to Gary Numan’s seminal “Cars,” and the line “I’ve started to think about leaving tonight” turned in my head as a moment of crisis for a character. The story grew from there, and the line stuck as the title of the piece.

I’m not the only one, of course. Alison Gaylin (Crime Plus Music, If I Die Tonight) uses music to set the mood when writing, although she finds music with lyrics too distracting. “On the other hand,” she says, “I love to use songs in my books to help set the time period and in characterization. You can tell a lot about a character by what songs they like (and hate!).”

I remember Wallace Stroby’s Gone ‘til November contained many musical references, so he handed out CDs of the songs at his book launch. Says Stroby, “You had Johnny Cash songs next to hip-hop songs next to old soul songs, but they were all on the same theme — people leaving and never coming back. The whole tone I was going for in the book was reflected in the songs.”

Music then has its charms to soothe (read: prompt, inspire) the savage breast (of the writer), so that he or she may in-turn write about savagery.

***

You can get Tiny Crimes: Very Short Tales of Mystery and Murder here.

And you can pre-order The Black Car Business Volume 2 right here.

Monday, June 25, 2018

Summer Reads

With long, lazy days and the sun just right for lounging, summer is a great time to slow down and kick back with a good novel. Who better to give suggestions for summer books than book-worms, fiction aficionados and storytellers? Esteemed authors and experts tell Do Some Damage what they are excited to read this summer.

☀☀☀

Bill Baber’s Summer Reading List

Hey, summer comes early in southern Arizona. After a couple of weeks of hundred degree temps, we drove to Puerto Penasco to cool off along the Sea Of Cortez.

I took Tom Pitts with me. Or rather AMERICAN STATIC by Tom. That kicked off my summer reads. Wow, what a start. Could not turn the pages fast enough!

Currently reading EVERGLADE by Greg Barth. It is the latest in the SELENA series. Selena, Barth, enough said.

Did a reading in Tucson with Chris DeWildt last week. Scored a copy of his latest SUBURBAN DICK. It’s burning a hole in my night stand.

Also in my TBR pile is a book I am late getting to. SHE RIDES SHOTGUN by Jordan Harper.

Lastly, my wife and I are going to Maui to end the summer. A friend recommended BLUE LATITUDES by Tony Horowitz. He and a friend retrace Captain Cook’s South Seas route in a sailboat.

Almost forgot I’ll have to squeeze in a couple of Joe Clifford’s JAY PORTER books. I’m falling behind and he’s churning them out quicker than my book buying budget can keep up with!

BILL BABER’S crime fiction and poetry have appeared widely online and in numerous anthologies including Betrayed from Authors on the Air Press. His writing has earned Derringer Prize and best of the Net consideration. A book of his poetry, Where the Wind Comes to Play was published by Berberis Press in 2011. He lives in Tucson with his wife and a spoiled dog and has been known to cross the border for a cold beer. His story " Bad Night On The Border " will appear in IT WAS A DARK AND STORMY NIGHT, the second western anthology in a series edited by Scott Harris. He will also have a story coming at Story and Grit. He is working on his first novel.

☀☀☀

E.A. Cook's Summer Reading List

The top five on my summer reading list are, in no particular order:

ZERO AVENUE by Dietrich Kalteis.

I read Kalteis’ historical crime fiction novel HOUSE of BLAZES –There’s hidden loot, ex-cons, crooked cops and transvestite prostitutes, oh my, set during the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and the ensuing great fire that killed and ate everything in it’s path. His descriptive writing, tight dialogue, great and colorful characters told with an economy of words makes me want to catch up and read his next novel written in 2017 - ZERO AVENUE- a hardcore crime novel set in the early punk scene in Vancouver. Can’t wait.

MR. TENDER by Carter Wilson.

I’m currently reading this one and it’s every bit the psychological thriller that I knew it would be. Carter wrote a book a few years ago – THE BOY IN THE WOODS – that was such a stand-out crime thriller that the story is still fresh in my mind and I doubt it will ever fade. MR. TENDER is good like that.

CLEANING UP FINN by Sarah M. Chen.

Back in March I read The Last Second Chance – a gut punch of flash fiction by Chen that left me mumbling about how damn good it was and how she gets it. I’m excited to read CLEANING UP FINN.

AMERICAN STATIC by Tom Pitts

I don’t know what it’s about, haven’t read the synopsis or any of the reviews, but Tom Pitts wrote it. He wrote HUSTLE, and HUSTLE shook me and made me want two showers.

THE BITCH PIT by Chris Pimental

I read this 11 years ago when it was still a rough draft. It’s been picked up by Dark Silo Press and the storm is coming. Chris is crime fiction’s prodigal son and best kept secret, but this book will blow the lid off.

Cook (Eddy) has lived a life that rivals the characters that he writes about. As a young man he spent years traveling around North America covering 43 states and trips over the borders of Mexico and Canada. He traveled by box car, hitchhiking, and as a carny traveling with 8 different shows off and on over twelve seasons. He’s worked as a hot dog vendor and face painter in New Orleans and has been an Account Executive for print advertising, owned a private investigations company, and is a recently retired cabby and writing full time. Eddy lives in Ft. Collins, Colorado with his tribe. You can find his novels, including Further and Rusk: A Robineux Tale, at Amazon.com.

☀☀☀

Kate Malmon's Summer Reading List

OK. Here are the Top 5 Books on my Summer 2018 Reading list!

JAR OF HEARTS by Jennifer Hillier: This is clearly the Book of the Summer. Everyone is talking about it and I can’t wait to find out why.

GALE FORCE by Owen Laukkanen: What’s summer without boats? Admittedly, the salvage boats in this book aren’t the sea-faring vessels you usually think about during the summer.

THE UPPER HAND by Johnny Shaw: I will always read Shaw’s latest release. Full disclosure, I’ve already read this one and it does not disappoint. It comes out July 3, 2018, and you should pre-order it now.

GIRL WAITS WITH GUN by Amy Stewart: To be honest, I picked this up because it had a fantastic cover. Stewart’s book stars Constance Kopp, one of the nation’s first female sheriff’s deputies. Who doesn’t like female crime fighters?

CON ARTIST by Fred Van Lente: Someone is murdered a San Diego Comicon. This book has everything I love – murder, comic books, people dressed up as superheroes, and did I mention murder?

Kate Malmon is a reviewer for Crimespree Magazine and the Writer Types podcast. When she’s not reading, you can find her on her bike or walking her Boston Terrier, Franklin. She and partner in crime Dan Malmon recently edited an anthology called, KILLING MALMON with all the money going to MS research.

http://crimespreemag.com/

☀☀☀

Richard Vialet's Summer Reading List

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SEVEN KILLINGS by Marlon James - This is actually a re-read for me but an advanced copy of this book was the first thing I read by Marlon James back in 2014 and I felt like I wasn't ready for it when it came out. Since then I've read his previous novels and loved them, with THE BOOK OF NIGHT WOMEN becoming my favorite book. So I'm excited to jump back into this challenging read again and see how I feel about it now.

THE MAN WHO CAME UPTOWN by George Pelecanos - It's a brand new Pelecanos book and it's being released late summer. Is any other reason needed for this to be on the list?

The last two books are by writers who I've been excited about getting more acquainted with:

SUNBURN by Laura Lippman - I've previously only read Lippman's story collection HARDLY KNEW HER, but I've been meaning to read more from this popular author and the reviews from this one promises a twisty noir, which is something that's always up my alley.

THE LINE THAT HELD US by David Joy - David Joy is almost universally praised and I've purchased every one of his book when they've been released, but I keep putting them off for other things (there are just too many books and not enough time!). I'm meaning to change that soon, especially because this one sounds particularly awesome

*If I can add a few honorable mentions, then I'm also excited about reading Jen Conley's CANNIBAL'S, Lou Berney's THE LONG AND FARAWAY GONE, and Angel Luis Colón's MEAT CITY ON FIRE this summer. Hopefully I can fit them all in!

Richard is a cinematographer based in Los Angeles, CA and Atlanta, GA, with feature film credits such as ACRIMONY, LAVALANTULA, and the upcoming NOBODY'S FOOL. He loves reading and in his free time, he writes his humble opinions at his blog: Black Guys Do Read.

Sunday, June 24, 2018

Get Out the Vote

By Claire Booth

California’s

primary election was earlier this month, and in my county they threw a few

interesting twists into the process. We were one of only a handful of counties

statewide to test several new procedures, like early voting and drop-box

locations.

I know other

states have some or all of these features already. We just like to take our

time here in the Golden State. Make sure something works on a small scale

before we go big and it all goes to hell.

Anyway, one

change this election cycle was that every registered voter automatically got a

mail-in ballot. Before, you had to request one, so lots of people didn’t bother

and then forgot to vote in person on Election Day. To try to increase turnout this

time, the mail-in ballot came in the mail with all your other election

paperwork whether you wanted it or not. And boy, did you have options as far as

returning it. You could mail it in anytime up to and including Election Day.

You could fill it out at home and take it to a drop-box location (list

helpfully enclosed in the envelope). You could take it in person to a polling

place. Lots of great, easy options.

So what went

wrong? (Because you know things did.) First – and this was not clear on the

helpful list – the drop-boxes were only accessible during that location’s operating

hours. So voters who showed up at 7:30 a.m. on Election Day with their

completed mail-in ballots, expecting to drop and go because that’s when polling

places are open, ended up shoving envelopes under the doors of closed libraries

and churches. It was as if grown adults were forced to revert to their

childhoods, when they’d slide notes under their sisters’ bedroom doors

apologizing for hitting them.

Second,

people are procrastinators. Most of them waited until Election Day to mail or

turn in that mail-in ballot. Which meant that counting the votes is taking forever. A week after the June 5

Election Day, the county election office announced that it still had 200,000left to process. That is not a typo. It is a good news/bad news number. The

good news is that if most of those are valid, it would increase voter turnout

by more than 16 percent, to more than 46 percent of registered voters. That is

an enormous amount for a non-presidential year. The bad news is that there are

races that still don’t have official results yet. Processing that many mail-in

ballots takes a lot of time, my friends (especially if you’re retrieving them

from under the doors of libraries and churches – because yes, those ones did

count).

But for me,

the most flawed aspect of this Election Day was less any kind of error and more

the lack of a choice. I am one of those people that goes to the polling place.

Every time. I chat with the workers, I fill in my little bubbles, I feed the

paper into the machine, I chat some more, I slap on my “I Voted” sticker, and I

saunter out into the sunlight of democracy. It makes for a good day’s work.

This time,

the polling places were consolidated, so instead of your neighborhood location,

there were a few centralized “hubs.” Boo. That was no fun. I didn’t recognize

the poll workers, nobody bothered to bring cookies, and the signage sucked. It

did not make me want to increase my voter turnout. Has this new procedure

beaten me into submission? Will I now succumb and just put the damn thing in

the mail every time? Probably not, if only because I’m spectacularly stubborn. I’ll

keep voting in person. But I do want my neighborhood polling place back. Heck,

neighborhoods get harder and harder to maintain in today’s world as it is.

Don’t take away one of their bedrock foundations.

I’ve voted in

churches, in libraries, in the county registrar’s office. The best polling

place was when I lived in Bellevue, Wash., just across from Seattle. There was

an assisted living facility just down the street, and that was the neighborhood

polling place. There has never been a better pairing of people and activity.

Those residents hung bunting and flags, made cookies, and stood at the door to

welcome you. And you could tell that it made their day. It made mine, too. No

drop box is ever going to equal that.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)