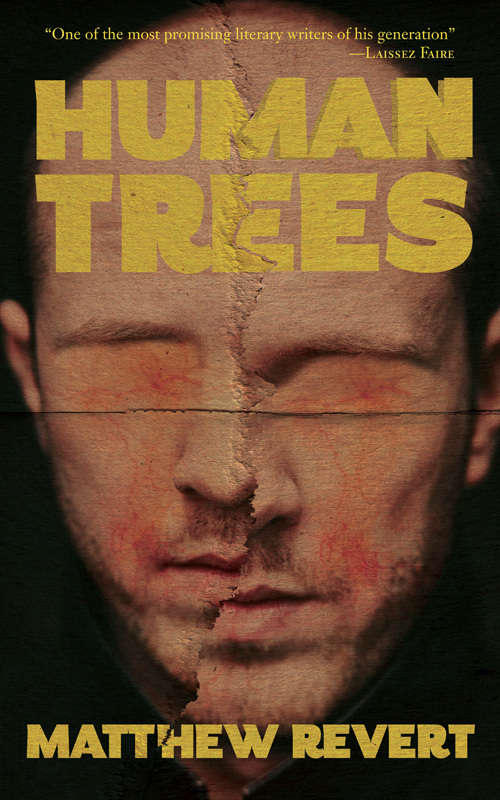

Scott's note: In the last few years, Matthew Revert has done so many great covers for books from indie presses, I almost take his artistry in this area for granted. The covers he's done for novels from Broken River Books, Lazy Fascist Press, Eraserhead Press, and Civil Coping Mechanisms, among many others, are things of beauty. He also happens to be a novelist himself, and his new book, Human Trees, has just come out. The thing is, it's been a bit of a struggle for this book to come to light, and that's what Matthew talks about here, in this piece.

And so, here he is.

Climbing Human Trees by Matthew Revert

The impossibility of exactitude when relying on memory gives me something of a thrill. When I was asked to write about why my latest book, Human Trees, took four years to arrive, there is little choice but to refer to my ever-contorting bank of imperfect memory. How accurate any of this information is cannot be determined – and if the proprietor of these memories cannot vouch for their validity, why should you lend them your faith? I would suggest you don’t. Consider this writing another story born of the same stasis Human Trees exists within – a companion piece.

My previous book, Basal Ganglia, was released at a difficult time in my life. As the release date approached, my father suddenly died in a manner too unpleasant to recount. Within weeks, Basal Ganglia was sent off into the world utterly divorced from my new sense of loss. The book, as it was, had no knowledge of my father’s death, containing words beyond my context. It felt like an act of betrayal toward my father and I knew whatever I did next had to exist within the context of my loss. It was while cleaning out my father’s house in preparation for whomever the government saw fit to replace him with that I started writing a book in harmony with my new context. I journeyed throughout the writing of this book with difficulty, using documentary-like descriptions of tragic moments. About 30,000 words in, I stopped. Not only was this book not Human Trees, this book was not supposed to be a book. Beyond my own self-serving needs, what was the point in such an exercise? I stepped away from the writing and simply learned how to exist in a world wherein my father did not.

And so, here he is.

Climbing Human Trees by Matthew Revert

The impossibility of exactitude when relying on memory gives me something of a thrill. When I was asked to write about why my latest book, Human Trees, took four years to arrive, there is little choice but to refer to my ever-contorting bank of imperfect memory. How accurate any of this information is cannot be determined – and if the proprietor of these memories cannot vouch for their validity, why should you lend them your faith? I would suggest you don’t. Consider this writing another story born of the same stasis Human Trees exists within – a companion piece.

My previous book, Basal Ganglia, was released at a difficult time in my life. As the release date approached, my father suddenly died in a manner too unpleasant to recount. Within weeks, Basal Ganglia was sent off into the world utterly divorced from my new sense of loss. The book, as it was, had no knowledge of my father’s death, containing words beyond my context. It felt like an act of betrayal toward my father and I knew whatever I did next had to exist within the context of my loss. It was while cleaning out my father’s house in preparation for whomever the government saw fit to replace him with that I started writing a book in harmony with my new context. I journeyed throughout the writing of this book with difficulty, using documentary-like descriptions of tragic moments. About 30,000 words in, I stopped. Not only was this book not Human Trees, this book was not supposed to be a book. Beyond my own self-serving needs, what was the point in such an exercise? I stepped away from the writing and simply learned how to exist in a world wherein my father did not.

It’s difficult to say how much time passed before I tried to write again. I felt my mind trying to form stories, but none of them were removed enough from the source, so I suppressed them. If I was truly going to write about the loss of my father, then I also had to write about the loss of my mother a decade earlier. If I was going to write a book about the loss of my parents it could not be about them, yet it could be about nothing else. The title Human Trees did not arrive until some time after I finished writing the contents the title was chosen to represent. It was lifted from a Cioran passage pertaining to sexual impulse, but I removed it from this context and viewed it in isolation as a terrifying image of stasis – the same stasis the book was trapped within. If there’s one thing my father’s death made me reflect upon, it was the nature of family and the ways a family unit can destroy itself without emotional maintenance. The vast majority of my extended family live in the UK, which distils my experience of family into two siblings and myself. With such a streamlined family unit, it was easier to maintain and I began to wonder how much I took this for granted. Circumstance had forced us to be there for one another and it was with a feeling of relief that we thrived. Human Trees exists in a world where we didn’t thrive – in a world where my parents were not the paragon of love and support they so effortlessly were. It was written in honour of what they were not, yet with the pain their unfair deaths instilled within me. These are words of love wearing unaddressed resentment.

In all truth, only about six months of my four-year absence consisted of writing Human Trees. I managed to submit the final manuscript to my publisher, Lazy Fascist Press a few days before I was scheduled to leave for New York. As I’m sure is common, after I submitted it, I did my best not to think about it, opting instead to wait for my publisher to come to me. Shortly after I returned to Australia, Cameron Pierce at Lazy Fascist contacted me in a manner I did not expect. It was his contention that Human Trees was my ‘break out’ book and he believed Lazy Fascist lacked the reach to give it the push it needed to be read by as many people as possible. With my permission, he acted as my agent and contacted some bigger presses with the hope one of them would add Human Trees to their roster. I had never been in a situation like this before. It was an honour to know my publisher believed in my work so strongly and although it meant I would have to wait, we both agreed the potential payoff was worth it.

The two years that followed this decision became a manifestation of the stasis Human Trees explores in such detail. It was poetic in a way and a part of me even started to enjoy the limbo my book was now trapped within. The first of my preferred presses kindly rejected the manuscript in a timely manner. We immediately galvanised and sent it elsewhere. This is the point I waved goodbye to my book and learned to no longer afford it thought. During this time, I sent Human Trees to a number of close friends hoping to get feedback, but very few of them read it. I harboured no resentment. It began to feel as though this was not a book that wanted to be read. It was projecting something that allowed it to evade the eyes of those it contacted.

I consider what it meant to wait for the second publisher’s response because the truth is I was no longer waiting. That year saw the arrival of a deep depression that stifled my momentum and having a book lost within the submission process was nothing compared to having a mind lost within the thought process. I no longer had a desire to explore writing. My musical activities were starting to find an audience, so I gave what little mental energy I had to that. It is safe to say I was no longer a writer. Human Trees was slowly unwritten, my mind erasing its creation as though it were a trauma event the mind could not process without damage.

It was a Wednesday afternoon nearly 18 months after we submitted Human Trees to the second press that we received our rejection. Cameron conveyed this rejection to me while I sat at my work desk. I read his words and managed to attach them to a process I had nearly forgotten. We had an answer, which meant the stasis was jolted. I experienced a moment of panic, terrified that I would have to engage with my book again. The following few weeks were spent slowly compiling a list of publishers for whom Human Trees might fit. Upon compiling this list, I realised all of them were currently closed to unsolicited submissions. I seem to remember finding this quite amusing, although this could be one of those distortions of memory I am so fond of.

David Osborne of Broken River Books and I were conversing as we often did. I was relaying the tale of Human Trees to him and he provided me with several ‘I told you so’s’ I could not remember the genesis of (although I am sure there was one). Eventually he simply said, “just release it on Broken River”. I was taken aback by this. I asked for 24 hours to consider his request. Something happened to me within the 15 minutes after David’s suggestion. Broken River began to feel like the right choice. It started to feel as though it had been the right choice all along and rather than listen, I sent Human Trees on a vacation to nowhere. We fast-tracked the release (an idea that strikes me as hilarious given how slow this track has ultimately been) and Human Trees was available within 6 weeks of his suggestion.

The two years that followed this decision became a manifestation of the stasis Human Trees explores in such detail. It was poetic in a way and a part of me even started to enjoy the limbo my book was now trapped within. The first of my preferred presses kindly rejected the manuscript in a timely manner. We immediately galvanised and sent it elsewhere. This is the point I waved goodbye to my book and learned to no longer afford it thought. During this time, I sent Human Trees to a number of close friends hoping to get feedback, but very few of them read it. I harboured no resentment. It began to feel as though this was not a book that wanted to be read. It was projecting something that allowed it to evade the eyes of those it contacted.

I consider what it meant to wait for the second publisher’s response because the truth is I was no longer waiting. That year saw the arrival of a deep depression that stifled my momentum and having a book lost within the submission process was nothing compared to having a mind lost within the thought process. I no longer had a desire to explore writing. My musical activities were starting to find an audience, so I gave what little mental energy I had to that. It is safe to say I was no longer a writer. Human Trees was slowly unwritten, my mind erasing its creation as though it were a trauma event the mind could not process without damage.

It was a Wednesday afternoon nearly 18 months after we submitted Human Trees to the second press that we received our rejection. Cameron conveyed this rejection to me while I sat at my work desk. I read his words and managed to attach them to a process I had nearly forgotten. We had an answer, which meant the stasis was jolted. I experienced a moment of panic, terrified that I would have to engage with my book again. The following few weeks were spent slowly compiling a list of publishers for whom Human Trees might fit. Upon compiling this list, I realised all of them were currently closed to unsolicited submissions. I seem to remember finding this quite amusing, although this could be one of those distortions of memory I am so fond of.

David Osborne of Broken River Books and I were conversing as we often did. I was relaying the tale of Human Trees to him and he provided me with several ‘I told you so’s’ I could not remember the genesis of (although I am sure there was one). Eventually he simply said, “just release it on Broken River”. I was taken aback by this. I asked for 24 hours to consider his request. Something happened to me within the 15 minutes after David’s suggestion. Broken River began to feel like the right choice. It started to feel as though it had been the right choice all along and rather than listen, I sent Human Trees on a vacation to nowhere. We fast-tracked the release (an idea that strikes me as hilarious given how slow this track has ultimately been) and Human Trees was available within 6 weeks of his suggestion.

In the three weeks since Human Trees was released, I am amazed by how well it’s doing. Readers are finding it and responding with enthusiasm. I have had to relearn my relationship with the book and the process of writing in general. Over the course of this experience, it is as though my book has earned the right to its content. It has now lived what it conveys and I have been given the rare opportunity to watch it live, both within me and beyond me. Its words reside in other minds now and those other minds can attribute to it whatever meaning they like. It is liberating to feel this separation. I am no longer responsible for its care.

No comments:

Post a Comment