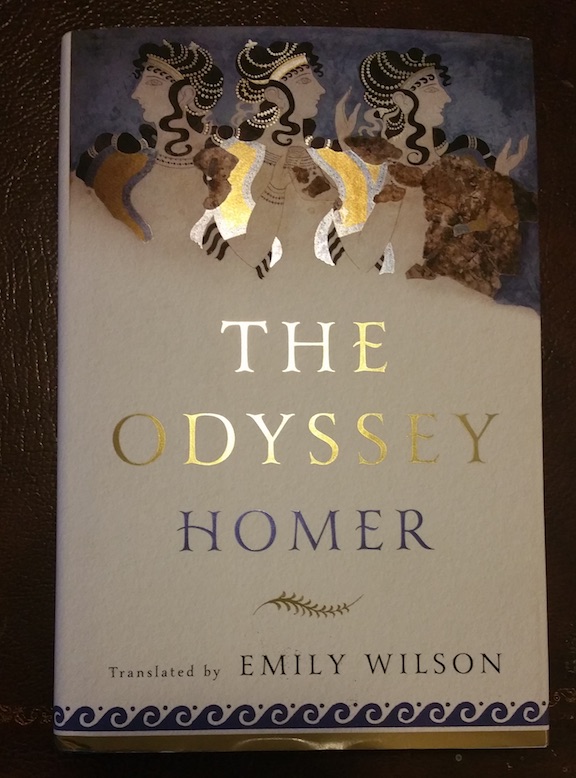

My Odyssey began with Emily Wilson's beautiful translation of The Odyssey, which has been called feminist, but in reality is just not chauvinist. She strips the bias of prior translations that turned servant-girls into "sluts" and gives us a view of the man as the oldest texts depict him. And it isn't pretty, though it is utterly compelling. Odysseus is a cruel trickster who would be chums with Reynard the Fox. We are supposed to empathize with him for being kept from home for twenty years, but it's easy to forget this is punishment. He urges the slaughter and enslavement of Hector's wife and family so they can't seek vengeance; he and his men insult Poseidon and Aeolus at every turn. They are not so much victims of the cyclops as sheep rustlers caught in the act, and his cruel joking nature is what gets him his comeuppance every time.

It's still a story I love, even if Odysseus is, as the first line reads, a complicated man. And no matter if you read the story ages ago, absorbed it through culture or watched a movie of it, I highly recommend reading Wilson's new translation to help parse this Ur-epic's influence of every story written after. And yes, I will be reading Gilgamesh soon, which predates it.

What of Beowulf? He's been taken to task before, as with Grendel by John Gardner, a favorite of mine as a youth. Maria Dahvana Headley goes much further in The Mere Wife, transplanting the story to the American suburbs and making it very difficult to tell who exactly the monsters are. It's not a mirror of Beowulf but a story inspired by it, so while someone loses an arm, it's not a scene for scene retelling. Headley writes with a mythic power, and instead of a mead hall of old men, the planned community of Herot Hall is run by the wives of rich men, who pull the strings and play kingmaker with as much intrigue as a thousand pages of Game of Thrones. Whoopsie! (That's an in-joke, you'll have to read the book to get it).

Their community is built on the bones of an older one, poor unnamed people who built the now-abandoned train station, which the Herot family wants to rebuild into a gentrified commuter delight.

Dana Mills, a soldier from that older community, returns home with child and raises young "Gren" up in the mountains, looking down on the land that was taken from her family. The Herots have a son Gren's age and the two become friends, and later, more than friends, a bond that brings the two worlds together and tears them apart.

Headley uses the old story to tell one about our modern day, and like Grendel, sides with those who aren't allowed in the hall instead of those welcomed in as heroes. The lady of Herot Hall is a great villain because we understand her motives, and sympathize with the cage she was born into.

Circe by Madeline Miller may be my favorite of the bunch, and if you love women behaving badly, she is one of the most infamous. She starts as a small nymph daughter of the sun god, who scorches children who ask too many questions or not bow to his narcissism, and quickly learns to survive in the shadows of the gods as she grows and learns her own unique powers: she is something entirely new, a witch, a human who can harness powers to defy the gods. Needless to say this is dangerous, and is how you get exiled to a rocky island for life. Which is where she meets Odysseus. It's a testament to Miller's storytelling that this happens late in the narrative and I stopped waiting it to happen. She weaves the totality of Greek myth around Circe's life, and the gods are capricious, cruel egomaniacs who demand sacrifice from humans when they aren't torturing us for their entertainment. Circe is only a little better, but her vengeance is sweet.

Circe is the perfect follow-up to your re-read of The Odyssey, and you won't be disappointed. It's beautifully written and paced quickly even though it spans countless centuries of the immortal gods. Scylla has never been more terrifying, Odysseus never portrayed better--from the perspective of someone he wants to make a victim, but who traps him in turn--and I can't wait to read Miller's best-seller The Song of Achilles to see her take on the Trojan war.

In my own work, I rarely invoke myth anymore. I used to do it all the time, but now if it's there, it is buried deep. For me, that works better. Even if you don't know a certain myth directly, often you've absorbed it, so you don't need to know the labors of Hercules--that hitman from Olympus--to be influenced by them. For example when Laird Barron had Isaiah muck out stables in Blood Standard, we didn't have to ask who he was being compared to. And when Jay Desmarteaux throws a severed head that "petrifies" his enemies, you know he's about to release the kraken.

No comments:

Post a Comment