Let's talk audiobooks.

I know some people have a bias against merely listening to a book, versus doing the work of reading a book, and all told, reading can be a much different experience. A poor reader, or a voice that doesn't quite fit the narrator can make an audiobook harder to get into, and of course, you're exercising a different part of your brain when you listen. But lately audiobooks have been my jam.

I've had to do a lot of driving recently, and when I was walking five miles a day, getting through a few chapters of the book I was listening to was great motivation (actually, after I finish this, I intend to walk my dogs and listen to more of Roxane Gay's new memoir, Hunger).

I've always been a voracious reader, but with adulthood, parenthood, and all kinds of responsibilities, I find my reading time being sucked away until bedtime, where I inevitably fall asleep and have to track back over the last few pages I "read" before passing out. Audio has been a godsend in this regard. I have never been able to read two novels at once. I just can't do it. The narratives and voice get jumbled in my brain and I can't keep up with what is going on in both books and whatever writing project I'm working on.

This problem is somehow eliminated when I "read" an audiobook and a regular book at the same time. I mentioned listening to Roxane Gay reading Hunger on my drives. I got through Sharp Objects just recently, all while reading The Passenger by Lisa Lutz, and now, flying through Danny Gardner's A Negro and an Ofay, a book I've been excited to read for almost a year. It's renewed my love and energy for reading, even as time is short. I find myself eagerly pulling out my phone to read an ebook in a waiting room instead of turning to Facebook or, my favorite time waster, Tetris.

I've always been reticent to judge someone for what they read, how they read, or how much they read. To me, the important thing with reading is that people do it. Stories are important, the work is important. If you want to read Twilight in paperback, or Borges on your iPhone, what do I care? I mean, read my book, and the books I'm featured in. Clearly I care about that. But otherwise? Three cheers for the many ways we can consume great writing.

I keep hearing that audiobooks are the future, the big moneymakers, the thing to cling to in your contracts for rights. Maybe there's something to that. For me, the audiobook doesn't take the place of reading something great, but fills time I'd otherwise "waste" with good books, and fills me with the joy of reading that leads me to my paperbacks and e-books. It's a great way to sample new writers and reinvigorate when reading seems to always be pushed aside for chores and responsibilities. My family is getting used to me listening to books while I make dinner, a time I'd usually reserve for checking social media between stirring what's on the stove or pacing around the kitchen.

As writers we must read. We must read a lot. Audiobooks are providing me a great way to get those books in and motivation to read even more.

Huzzah!

Friday, June 30, 2017

Thursday, June 29, 2017

Author Interview

By Sam Belacqua

I've been known to take part in author interviews, from both sides of the bar. Coming up with questions can be tough. Original. Thoughty. The sort of question that calls for more than a one-sentence response.

I've read horrible, dull interviews. I've read interviews in which it was clear the questioner hadn't read the book. Heck, I've read reviews where the reviewer hadn't read the book. And I've read interviews where it seemed the author hadn't read the book.

Anyhoo, if you're struggling to come up with questions for an author interview, I'm here to help. Whether you're hosting an author podcast or blogging or writing for print, feel free to use these questions below. Most of them were extras that I didn't get the chance to ask, for one reason or another. You're welcome.

I've been known to take part in author interviews, from both sides of the bar. Coming up with questions can be tough. Original. Thoughty. The sort of question that calls for more than a one-sentence response.

I've read horrible, dull interviews. I've read interviews in which it was clear the questioner hadn't read the book. Heck, I've read reviews where the reviewer hadn't read the book. And I've read interviews where it seemed the author hadn't read the book.

Anyhoo, if you're struggling to come up with questions for an author interview, I'm here to help. Whether you're hosting an author podcast or blogging or writing for print, feel free to use these questions below. Most of them were extras that I didn't get the chance to ask, for one reason or another. You're welcome.

***

Your new novel, THE GIRL WITH THE CARETAKER’S DAUGHTER, is

your twentieth in the series. Many authors seem to have run out of ideas after

the seventh or eighth novel in a series, but that doesn’t seem to bother you.

What’s your secret?

A few years ago I remember reading in Variety that one of

your novels had been optioned for a movie, but it seems like nothing ever came

of that. What happened?

Your literary novel, JAMES McGAVIN’S DECAYING MOLARS: A

NOVEL, received 86 positive reviews in various Brooklyn media outlets, but has a 2.0

rating on seven Amazon reviews. How many years did you work for that literary

website in Brooklyn?

I read on someone's post about you that you tend to write in coffee shops. Is an Americano the one with froth or is that a latte?

I noticed that you seem be taking up to seven months between

novels, with only a Kindle single to tide your fans over. What takes so long?

Your website has a songlist for each of your novels. What am

I supposed to do with that? Listen to the songs when I read your book? On

repeat? The playlists are about 30 minutes or so and it takes me a long time to get through your books. So, all the playlists together? Or if I like The White Stripes, then I’m supposed to like your book?

Please advise.

How would you describe your new novel to someone who hasn’t

read it, but needs to ask questions about it?

I subscribed to your Author Newsletter, "Read, Write, and Blue," because you had an

interview in it with Don Winslow one time, and he’s a really great writer. Now your

newsletter is mostly links to buy “swag” for your books and a low res PDF of

your upcoming blog tour. How do I unsubscribe?

What’s the worst reading experience you’ve ever had? Ever

had a reading where no one showed up or maybe some people did, but no one

bought any books? What’s that like?

Your agent, Karen Jenkins, reps some of my favorite authors.

This isn’t part of the interview, but I queried her a few weeks ago with the

first 40 pages a novel I’m working on. Would it be OK if you emailed her about

my writing? Is that called a blurb?

Wednesday, June 28, 2017

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to This Blog Post

by Holly West

This is one of those weeks where I'm having trouble coming up with something to write about for this blog. That's a good thing, because it means my mental energy is being taken up by more substantial projects. So what I'm really saying is: my gain is your loss. Or something like that.

But something happened last night that was kind of funny. We were watching the season finale of Veep and my former shrink popped up in one of the scenes. I mean "popped up" literally--Selena Meyer's legs were up in stirrups because she was giving birth and suddenly his head popped up from between them. He was playing the delivery doctor. He's a psychiatrist by trade and thus he went to actual medical school, so in this case he's a doctor just playing one on TV.

This is one of those weeks where I'm having trouble coming up with something to write about for this blog. That's a good thing, because it means my mental energy is being taken up by more substantial projects. So what I'm really saying is: my gain is your loss. Or something like that.

But something happened last night that was kind of funny. We were watching the season finale of Veep and my former shrink popped up in one of the scenes. I mean "popped up" literally--Selena Meyer's legs were up in stirrups because she was giving birth and suddenly his head popped up from between them. He was playing the delivery doctor. He's a psychiatrist by trade and thus he went to actual medical school, so in this case he's a doctor just playing one on TV.

Mind you, he's a practicing psychiatrist who I'm pretty sure still sees patients. He also appears on TV news programs a lot to explain different medical issues. Like when Carrie Fisher's death certificate was released he went on TV to talk about the drugs she had in her system and how they might've contributed to her death. One of his career goals was to be a "pop-culture" shrink, and he's been fairly successful. Think Doctor Oz without the quackery.

But it's not like my doctor was "Psychiatrist to the Stars," at least not when I was his patient. He was the UCLA intern who assessed my situation when my primary care physician referred me to a therapist. He was at the end of one part of his training and invited me to stay with him when he went on to the next part of his training.

Wait, why am I telling you all of this?

But it's not like my doctor was "Psychiatrist to the Stars," at least not when I was his patient. He was the UCLA intern who assessed my situation when my primary care physician referred me to a therapist. He was at the end of one part of his training and invited me to stay with him when he went on to the next part of his training.

Wait, why am I telling you all of this?

Anyway, that Veep scene wasn't the first time he just showed up on TV out of nowhere. Years ago when I was his patient, I saw him on a commercial for a bad breath remedy. He played the guy with bad breath who was grossing his dance partner out. Imagine asking your shrink if it's possible you might have seen him in a television commercial for something like "Amazing Breath?" Imagine him saying yes? That's pretty much what happened.

I'm not gonna lie, I started second-guessing our relationship after that.

I'm not gonna lie, I started second-guessing our relationship after that.

Tuesday, June 27, 2017

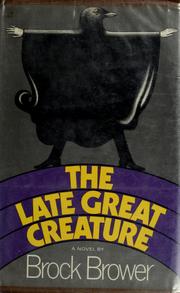

Little Known but So Good: The Late Great Creature

Who as a reader doesn't like coming

across a great novel that's been long neglected? You read it and want to tell

other people about it. The Late Great Creature by Brock Brower

is one of those great little-known novels, a brilliant piece of

work published in 1971. I read it a few years ago, and I've been

mentioning it to friends ever since. I can't even remember now where I

found out about it. I think it was discussed in some piece I was reading

- that's all I recall - and it whet my interest so much that I ordered it used

from the Advanced Book Exchange. It was out of print at the time and had

been for decades.

Part Hollywood novel, part horror story, part intriguing character study,

it's a book not much like anything else I've ever read. It's the fictional

biography of an aging horror movie star named Simon Moro. Simon, who was born

in 1900, apparently in Vienna, was a huge star in the 30's and 40's, playing

such things as a mad pedophile in Fritz Lang's Zeppelin and,

in his American debut, The Moth, also starring Fay Wray. By WWII he

was already in decline, playing Nazis in war movies and the monster in the

ultra low budget Gila Man series. But the central point of the novel is his

last film, a very Roger Corman like production of The Raven, being

made in the late 1960s.

Moro's story is told in three parts. In each part, we get a different narrator - first a cynical journalist, then The Raven's very shallow director, and in the last section, Moro himself. In this last part, it becomes clear what Moro, for his grand finale as an actor, has up his sleeve. Suffice it to say, it is an act that is quite bizarre, and he performs it in the the Manhattan theater where The Raven has its premiere. It is his last determined attempt to deliver a memorable shock to an increasingly unshockable world. What he does is both grotesque and hilarious, a grand final gesture by an over the top personality.

This book is a terrific satire on celebrity culture and an affectionate send-up of the horror genre. Simon Moro is a person who is both comic and appalling, an unforgettable character. He reflects the novel itself, a book both extremely dark and funny.

As I say, the book was long out of print, but Overlook Press brought out a

paperback edition of the novel in 2011, and you can find it now on Amazon,

including as an e-book.

Here's a couple of comments you'll find there, from none other than the likes of Joan Didion and James Ellroy.

"It's a wonderful book . . . like a circus with several brilliant performances going on at the same time . . . a real breaking through. I don't think anybody ever again will be able to dabble politely in mixing 'real life' and fiction." — Joan Didion

"A lost classic is rediscovered, repackaged, and preserved as a feast for a new generation of readers. The Late Great Creature is the history of a horror-film star and a treatise on human frailty and the innate human urge to seek the sublime through the grotesque. Brock Brower created a brilliantly observed and wholly synchronous work of art 40 years ago; now it is back to be savored and marveled at anew." — James Ellroy

Couldn't agree more with both of them.

Monday, June 26, 2017

Tom Pitts and AMERICAN STATIC or Meet Princess Quinn

It’s summer! Time to catch up on that teetering, tower of

TBR. One of the season’s most anticipated new books is finally out.

"I don’t know what’s better, his (Tom Pitts) writing or the story he is telling."

-David Nemeth, Noir Czar, Unlawful Acts

Fans of dark, gritty crime fiction have come to know the

name Tom Pitts. Author of FASTBALL, PIGGYBACK, and HUSTLE he is also

acquisitions editor at Gutter Books and Out of the Gutter Online. He fills his

24-hours. His new novel AMERICAN STATIC hit the streets June 26.

AMERICAN STATIC is a fast-paced crime thriller with a

mystery woven throughout. It plays out against the backdrop of Northern

California’s wine country, Oakland’s mean streets, and San Francisco’s peaks

and alleyways. The perfectly paced story is filled with corrupt cops and death

dealing gangsters.

With a chaotic writer’s schedule and O.J. vs The People

streaming on Netflix Tom Pitts is a busy man, but we wanted to learn more about

his pitch perfect and true to life characters.

To get some insight, Do Some Damage sat down with AMERICAN

STATIC’s lead instigator Quinn and author Tom Pitts. Quinn is a mysterious

stranger on a desperate search for his daughter. When he picks up innocent

protagonist Steven after the latter is beaten and left for dead the two set out

on the ride of their lives.

In hopes of learning more about this fascinating man I

filled my phone notepad with questions. Deep, meaningful questions probing and

delving the depths of his soul and heart. Questions that might lead to a deeper

insight into his demons and angels.

Then my kids were released from school. Summer vacation hit and

my phone has not been the same. They text friends. Search DIY slime recipes.

Listen to Pandora without closing the app, suck the battery and lose all files

in my notepad.

There are some awesome consequences, though. All vocal apps

now address me as Mrs. Snow, Mother of Dragons. I can, in certain circumstance,

speak another language as my girls have changed my texting capability to

Japanese only. Plus, every single app on my phone is princess related.

With that being said and Quinn’s patience already tested I

decided to just do it, dammit. Thank you, Shia.

Ladies and gentlemen please meet Quinn and let’s get ready

to play…

Which Disney Princess Are You?

Quinn: Wait … is

that a real question? ‘Cause I have some thoughts on the subject. Having had a

daughter of my own, the whole princess thing is—

Pitts: Hang on,

wait a second, I don’t mean to interrupt, but this is ridiculous. I get that

trying to do a different spin on things might be fun, but an online Disney

quiz? Aside from it being inappropriate for the subject matter, you’re opening

yourself up to scrutiny from the most litigious organization in the history of

copyright infringement.

Quinn: Eh, not

for nothin’, but you seem a bit uptight, Pitts. Let’s let the little lady have

her fun and play along. Who knows maybe you’ll learn something.

Pitts: She’s not

a little lady, she’s a writer trying to go against the grain of a tired format.

Saying shit like that is patronizing at the very least.

DSD: It’s okay,

Tom. I don’t mind-

Quinn: Tell you

what, I’ll take the quiz, you can sit tight and relax for a minute. There’s a

bottle of Jack in the truck, why don’t you go pour yourself a short one and have

one of my Marlboros.

Pitts: I don’t smoke.

Quinn: Ha! Right!

Maybe you should. Maybe that’s your problem. Look, we all got shit to do today.

I’m startin’ to feel like you’re just being disruptive. I’ll tell you

only once more, sit down.

Pitts: I don’t

like the look you’re giving me.

Quinn: Okay,

Marrietta, I’m sorry. Some people just can’t let go of their own shit long

enough to have a good time. Now … where were we?

DSD: Checking hair in Quinn’s mirrored glasses.

Huh? Oh, yea. Wait. Something with princess. Which princess are you? Here we go.

1. What was your favorite

subject in school?

A. Gym. I was always team

captain

B. History. I loved

learning how romantic things were back in the day.

C. Lunch. Chatting with

my friends was the best part of my day.

D. English. Getting lost

in a book is so dreamy.

E. French. I

couldn’t wait to travel the world.

Quinn: School.

Yeah, right. I think you gotta get your education outside of the four walls,

you know? Question authority, and all that? Fuck school.

2. How

long does it take you to get ready in the morning?

A. Fifteen minutes. Tops.

I like the natural yet pulled-together look.

B. Five minutes. Messy

hair? Don’t care. Hello messy pony.

C. Depends. I love to try

new things. Ask my mood?

D. Thirty minutes. That

is just my hair.

E. An hour.

Perfection doesn’t happen by accident.

Quinn: Fifteen

minutes. This perfection actually did happen by accident. Back in the joint, it

was up at 5:45 and in the chow line by 6. If you didn’t make it by 6, it was

white toast with no butter for you. Now that I’m out freewheeling, I guess I

could do what I like in the morning. Take my time, read the paper, jerk off,

whatever. But, you know, old habits die hard.

Flashes perfect pearly whites.

DSD: No time for

proper nutrition? Shame. Breakfast is the most important meal of the day.

3. When

it’s a chill day, what is your fav activity?

A. Curl up with a good

book. No shame in re-reading my favorites.

B. Hang with my besties.

C. Hit the mall.

Hopefully run into my secret crush.

D. Sports. If I’m not

running, skating, swimming or biking I’m practicing.

E. Spa day!!!

Quinn: Behind the

wheel, all day, no stopping. One straight fucking beeline to the border, baby.

DSD: Sounds like

someone is a fan of the gorgeous open-air markets in Rosarita. Is it the

glassware or the hand-wovens?

4. How

would you ask your secret crush on a date?

A. Just ask. Duh.

B. Stick a cute note on

their car or mailbox.

C. Pop the question

during half-time!!!

D. Plan a fun scavenger

hunt.

E. Chill. Send a

text. NBD.

Quinn: Me? I have

to ask? I don’t know if you noticed that waitress looking at me, but she is.

Chicks dig me, what can I say. Usually they’re the ones asking me out.

DSD: Notes waitress’ expression also resembles

“bad burrito face.” Absolutely. I can see that. Let’s move on.

5. You’re

having a sleepover with your besties. What will you and your posse probably do

all night long?

A. Video games.

B. An epic game of truth

or dare.

C. Mani/pedis, of course.

D. Stalk your secret

crush on social media.

E. Watch our fav

tearjerker.

Quinn: Besties?

What the hell is that? Like a cellie? If we’re locked down, I don’t want

someone crawling the walls. They better lay still and entertain themselves. You

think I need a weapon to shut someone up? Hell no. All I need is these two

hands.

DSD: Aha. So, you

like arts and crafts? Are you a modeling clay type or do you like to work with

wood?

6. What

is your go to flirting move?

A. A subtle hair flip is

perfect.

B. Being super, duper

nice. Make them cookies!!!!

C. Show off.

D. Ramble on and on until

we find something in common.

E. Play it cool.

Act like I could care less.

Quinn: My smile,

it’s all I need. I’ve been told many times I got movie start good-looks. Hell,

I flash this grin at you and before you know it, I’m at your kitchen table and

you’re telling me your deepest darkest secrets. Lifts chin. Smiles.

DSD: As long as

you brought the doughnuts. Stares at

phone.

7. Your

bestie is super stressed they will never have a date. What do you suggest?

A. The Gym. People who go

to the gym are dedicated and totally hot.

B. Church. It’s where all

the decent people go.

C. You can find love

anywhere. Just be open to it.

D. Hang out after work.

Friends of friends.

E. Love yourself

first and love will find you.

Quinn: Toughen

up, kid. We ain’t all cut out for a life full of love.

8. Describe

your fashion style.

A. Sporty.

B. Flirty.

C. Classic.

D. Trendy.

Quinn: You

kidding? Class-sick. Shit.

DSD: Regular

Robert Redford.

9. Describe

your perfect crush.

A. Popular and charming.

So many people can’t be wrong.

B. Captain of the

football team. Go team!!!

C. Tough on the outside,

sweet and sensitive on the inside.

D. Mysterious.

Misunderstood.

E. I have a crush

on everyone.

Quinn: I’m not

sure I understand this question. What’re you trying to say? Are you accusing me

of something?

Pitts: Whoa, hang

on. Don’t get excited. It’s just one of those online quizzes for fun.

Quinn: For fun?

Online? Who else is reading this? I thought it was just us three, you know,

having a good time. What the fuck, Miles? Who asked you to do this? You with

somebody? You know Ricardo? Don’t lie, I’m not always this nice. If I find out

you’re fucking with me, shit ain’t gonna end pretty.

DSD: I don’t know

a Ricardo. I know a Weddle. Let me just get your score.

RAPUNZEL

You are funny and gregarious, people say you have a great

sense of humor and that you always keep them smiling and in stitches. You are

constantly on the lookout for adventures and excitement. You will never settle

down.

Perfect.

Sunday, June 25, 2017

Marking a New Release

By Claire Booth

The launch of my next novel is

only two weeks away and I’m getting all kinds of ways ready to let people know

about it. One of these is the time-honored tradition of author swag. I’m not

one who does a wide array of things in this regard, but I do spend a lot of

time on my bookmarks.

The design I wanted to use wouldn’t

have worked without great cover art. I wanted to preserve the detail and

fantastic colors. So instead of reducing the cover to a small rectangle and

putting it on a small spot in the front, I kept it close to the original scale

and sliced it.

For both books, the choice of

which slice to use was obvious. For the first, it was the sinking showboat in

all its listing, smokestacked glory. And for the second, it was the solitary

figure standing in the middle of the shadowy woods armed only with a

flashlight. (He might have a gun ... you'll have to read the book to know for sure.)

|

| The inspiration for this comes from fellow author Susan Spann, who’s been “slicing” her cover art into bookmarks for a while and graciously gave me pointers. |

So I got rid of the title wording

and then turned it over to a wonderful friend of mine who also happens to be a

fantastic graphic designer. She chose arranged where the text would go and how it would look, and designed the back.

They came in the mail from the printer on Friday, and

I love them. And if you’re anywhere near me in the next couple of months, I’ll

give you one!

Saturday, June 24, 2017

Reading for Pleasure vs for Research

By

Scott D. Parker

How many of y’all writers out there read for research?

Now, I’m not talking about actual research, where you scour

the internet or books to make sure you have your facts correct for a historical

piece or to verify which bullets go into the gun your hero carries for a

thriller. I’m talking about reading other fiction books with a writer’s mind

involved.

For awhile now, I’ve read hard copies with a pencil in my

hand and I will mark up the book as I go along. I circle various passages or

great turns of phrase. This is especially true when I read westerns because I

gather a growing list of “western words” that I can deploy in my own writing.

But I also study how books are constructed. How many

chapters? How many sub-chapters? How many pages/words per chapter? How many

pages over all? How many total words? A few years ago, I broke down the first

100 pages of THE DA VINCI CODE to figure out why it’s such a page-turner. It’s

really not rocket science.

As fine as this practice is, it can also lead to reading

*only* for research. For example, I’m in western-writing mode in 2017. That’s

what I’m reading (mostly) and writing. Thus, the desire to read only westerns

is quite strong. But other books are pulling at my attention. I selected the

new Donald Westlake novel, FOREVER AND A DEATH, for my book club so I’m reading

it. BEACH LAWYER by Avery Duff is also on my Kindle. The oddball is a book by

Jim Beard written in the G.I. Joe Adventure Team Kindle Worlds Universe,

MYSTERY OF THE SUNKEN TOMB. A fellow book club member recommended it to me. I’ve

read a bit and it pretty darn good.

Which reminded me of the reason I (and all of us) read in the

first place: for pleasure. A good story told well is a great pleasure to

experience. So I’ve put my pencil down for a bit and engage in some pure summer

reading for no other purpose than to enjoy myself.

Y’all ever run up against the conundrum of reading for

pleasure vs. research?

Friday, June 23, 2017

Crime DOES Pay (For awhile)

A real life jewelry heist story...

Most heist stories focus on what goes wrong - whether it's during or after the robbery. A well-executed robbery where everything goes to plan and the thieves escape doesn't make for great story telling. Or does it?

Surely when a real life criminal decides to rob a jewelry store or start fencing stolen goods, they think they're going to live the high life. Who would submit themselves to so much risk if the payoff was continuing to live a normal, boring life with a shit job? Marvin Lewis figured it out.

I mean, he got caught. We wouldn't know the story if he didn't. But before he did, he bought the cars, the luxury watches, the clothes. He inserted himself in Oscar and Emmy parties and documented his moneyed life on Instagram. He got another guy to keep robbing stores while he partied it up.

Usually, the only thieves who get to drive $200,000 dollar cars and hang with celebrities work for banks (badum-tss), but Marvin got his, at least for a little while.

The moral of the story is always supposed to be "crime doesn't pay" and while Marvin defended himself by claiming he'd always been rich, despite not wanting to discuss where his money came from in court, he's facing 57 years in prison. Hope the parties were worth it - and that a great director gets the rights.

Most heist stories focus on what goes wrong - whether it's during or after the robbery. A well-executed robbery where everything goes to plan and the thieves escape doesn't make for great story telling. Or does it?

Surely when a real life criminal decides to rob a jewelry store or start fencing stolen goods, they think they're going to live the high life. Who would submit themselves to so much risk if the payoff was continuing to live a normal, boring life with a shit job? Marvin Lewis figured it out.

I mean, he got caught. We wouldn't know the story if he didn't. But before he did, he bought the cars, the luxury watches, the clothes. He inserted himself in Oscar and Emmy parties and documented his moneyed life on Instagram. He got another guy to keep robbing stores while he partied it up.

Usually, the only thieves who get to drive $200,000 dollar cars and hang with celebrities work for banks (badum-tss), but Marvin got his, at least for a little while.

|

| His most heinous crime? "Loving" Ed Sheeran. |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)