Steve is going to murder me for doing this, but I got a little distracted this week. My wife and I have a baby on the way, so my focus hasn't been there. Because of that, and after reading Joelle's post, I decided it's time to republish an old blog post I wrote in 2007 about the death of the PI. I have edited it some:

William Ahearn posted this article on his website. It's entitled The Slow and Agonizing Death of the Private Investigator. Obviously, since I write PI novels, I have a stake in this.

The PI has grown and expanded to become both more realistic and at the same time more exciting...The PI no longer is a cypher in which to see the mystery unravel, if it ever was. The PI was always personally involved in their stories. Spade tried to solve the Falcon case because his partner was murdered--and despite him saying, that's just what you do, and his sleeping with his partner's wife--I have a feeling Spade cared. If Chandler hadn't died, it appeared that he was well on the way toward marrying Ms. Loring.

The character taken umbridge with the most seems to be Lew Archer, a character who had "feelings." It strikes me that Archer is the character who changed the least. He killed a man in the first novel and it was mentioned only once more in the course of the series. He met a woman in The Blue Hammer, but we don't know if anything came of that. In fact it seemed that Archer was the character who we most saw only the case. Did he beat anyone up? Occasionally, but not if he didn't have to. But we always knew he could. Did he care about people? Yes. But how cases affected him, that was always to be deduced by the reader.

Characters these days, the article seems to say, are only wussy men or women who drink for no reason or see psychiatrists or do things that the old PIs never did. Guess what, times change. The series has always been about the character. Things have to happen to the PI for us to care. Seeing a psychiatrist is an interesting way to look at a character's depths, I think. (It worked in THE SOPRANOS and Tony was still willing to get his hands dirty.) As far as the psycho sidekick works, yes, it has become a cliche (just like the bottle in the top drawer, the article seems to love so much).

I don't think the PI is dead. I think-at some point-it's going to thrive again. There are great PI writers out there... Pelecanos, Lippman, Crais, Parker, Lehane. (Kenzie was a character, one who was conflicted by his job, commited a murder when he saw no other option, but had to let an even worse character go, when he couldn't get to him. He got scared, he fell in love, and he got beat up. There was much more to him than the "clutter" on the surface.)

The detective stories were always about the detective in the novels. Marlowe played chess by himself (clutter?).. . Spade was after the killer of his partner, as I said, and didn't care much about the bird. Nick and Nora drank way too much and were much more interesting than whatever the case they were solving was.. Sherlock Holmes did cocaine..

(I would bring Spillane and Hammer into this more, but... alas... I haven't read him... and I'm willing to admit that. Though I've seen one of the movies (the one with the nuclear stuff and the house that blows up because of it) and it struck me as just plain silly.)

PIs who have psycho sidekicks (or don't) still get their hands dirty... which was one of the things you said the old PIs that you enjoyed did, but new ones didn't.

Kenzie and Gennaro executed a gang member (but the article says the reader threw the book across the room, so I'm not sure he got that far).

Tess Monaghan killed a man and it still comes up in the series.

Spenser has set up men to be murdered by his hands.

Evils Cole has killed many men and been willing to shoot, punch, and do what it takes to get the job done.

In fact, the point of the article is that the current PIs have a conscience. They kill but they feel it. It strikes me that if Hammer, Spade, and Marlowe didn't feel it when they killed someone (and Marlowe definitely felt it...James Bond felt it too in the novels)... they would be psychos themselves. They are not heroes, they are cold blooded killers as well.

I find the novels now, more exciting. There is more intense action and there are reprocussions to this action. I want to see how characters are affected by the violent worlds they live in... to me, that is more exciting.

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

Monday, July 30, 2012

Real Books That Don't Exist

The Edgar award winning author Jorge Luis Borges wrote about The Library of Babel, a library that is said to contain every book that was every written and will be written.

In that spirit I wanted to take a look at some of the books that are in the crime fiction section of The Library of Babel. But here's the kicker, there are indications that these books actually exist. We know this because they were talked about in interviews or mentioned in publicity material. They are real books that you can't read.

Every reader reaches a point in their life when they do the math of how many years left to live and how many books that are out there. What makes it even more daunting is knowing about a book from a favorite author that you may never get to read.

Blue at the Back of My Head by James Sallis

In an interview years ago Sallis made mention of this book that he was working on.

Bottomfeeders by James Sallis

In the same interview, and the very same comment, he also talked briefly about another work in progress that was further along.

Others of My Kind by James Sallis

In an interview with Craig McDonald Sallis talked about yet another book that was being working on.

Unnamed series by Lynn Kostoff

In the author bio of the hardback of The Long Fall there is mention of this:

Maybe this one became Late Rain?

The Work of Hands by Lynn Kostoff

Ken Bruen's children's book

Bruen's kids book was mentioned in at least two separate interviews a couple of years ago but there was never any information about it. I can't be the only one curious to read it.

The Dydak's by Duane Swierczynski

Years ago I had the opportunity to interview Duane Swierczynski. I asked him about a pair of minor characters that seemed like a missed opportunity, something to come back and explore later.

Whacker by Charlie Huston

Similarly, when I interviewed Charlie Huston we talked about a character that had appeared in two of his short stories.

Damn, now don't you wish you could go read those books right now. I contacted some of the authors mentioned here to try and get some information on these lost titles that still haven't seen the light of day.

Lynn Kostoff responded:

James Sallis responded:

In that spirit I wanted to take a look at some of the books that are in the crime fiction section of The Library of Babel. But here's the kicker, there are indications that these books actually exist. We know this because they were talked about in interviews or mentioned in publicity material. They are real books that you can't read.

Every reader reaches a point in their life when they do the math of how many years left to live and how many books that are out there. What makes it even more daunting is knowing about a book from a favorite author that you may never get to read.

Blue at the Back of My Head by James Sallis

In an interview years ago Sallis made mention of this book that he was working on.

I've also the opening chapters of a novel with the working title Blue At the Back of My Head, set in Arizona,...

Bottomfeeders by James Sallis

In the same interview, and the very same comment, he also talked briefly about another work in progress that was further along.

...and about half of one called Bottomfeeders, a comic novel about a cop killer, a take-off of sorts on The Seven Samurai.

Others of My Kind by James Sallis

In an interview with Craig McDonald Sallis talked about yet another book that was being working on.

-"I also wrote the draft of what will become my next novel, which is a non-genre novel called Others of My Kind."

-"it's the first time I've written a novel from a female point of view. And I didn't do it intentionally. I was walking again, and the voice in my ear was 'I', 'I', 'I' and it's a female 'I', so I had to write from a female point of view.

Unnamed series by Lynn Kostoff

In the author bio of the hardback of The Long Fall there is mention of this:

...and is at work on the first novel of a projected series featuring a patrolman from the North who's transplanted to the Myrtle Beach Police Department

Maybe this one became Late Rain?

The Work of Hands by Lynn Kostoff

The Work of Hands, which is set in 1986 in the Midwest. Its protagonist is a Public Relations man who cleans up scandals and fixes things. He believes he can always find a way to escape the consequences of his actions, but that belief is sorely tested when he has to clean up the aftermath of a large food poisoning outbreak. When this one is completed, I’d like to see what Ben Decovic and the others are up to.

Ken Bruen's children's book

Bruen's kids book was mentioned in at least two separate interviews a couple of years ago but there was never any information about it. I can't be the only one curious to read it.

-I wrote a children’s book, was assaulted on most all sides by

-‘Nearly killed me, honest to God. It seemed a natural progression from Priest, Cross and Sanctuary (the most recent books in the series) that the ultimate evil might appear. Never again though, too spooky. But it yielded a children's book which I wrote to rid meself of the demons of the Devil.’

The Dydak's by Duane Swierczynski

Years ago I had the opportunity to interview Duane Swierczynski. I asked him about a pair of minor characters that seemed like a missed opportunity, something to come back and explore later.

Brian Lindenmuth - The crime scene cleaners, The Dydak’s, were mentioned and seemed like a great source of material, but they never really made an appearance. I couldn’t shake the feeling that they had sections that were cut, are you thinking of perhaps using them at some later time. I know, it’s not really a question either, but would you care to comment.

Duane Swierczynski - I thought I might circle back to the Dydaks in THE BLONDE, but the situation never came up. However, they will be back in their novel. Sooner than you may think.

Whacker by Charlie Huston

Similarly, when I interviewed Charlie Huston we talked about a character that had appeared in two of his short stories.

Brian Lindenmuth - I love love love Det. Elizabeth “The Whacker” Borden. She might just be my favorite character of yours. Please for the love of everything holy tell me that we’ll get a novel with her.

Charlie Huston - That’s the plan. For me, anyway. The next trick will be getting a publisher interested. But, yes, I have a novel in mind. Basically the story of how Detective Borden got to be who she is. Which is basically the meanest, dirtiest, cruellest, most self-serving law enforcement officer ever.

Damn, now don't you wish you could go read those books right now. I contacted some of the authors mentioned here to try and get some information on these lost titles that still haven't seen the light of day.

Lynn Kostoff responded:

#1: author bio/Long Fall

At the time, I had been making notes on a crime novel using Myrtle Beach, SC, but that setting was basically where the novel would end; none of the characters in LATE RAIN were in it, except for Ben Decovic. The novel, whose working title I now can't remember, was set in a fictional rust belt city, Ryland, Ohio, an amalgamate of some of the iron and steel cities in northeast Ohio and western Pennsylvania where I grew up. That novel centered on the relationship between Ben Decovic, a homicide detective, and his cousin, Michael, who was the mayor of Ryland and coming up for re-election. I wanted to use some of the elements of what had happened economically, psychologically, emotionally, and culturally to that part of the country. Michael Decovic had started off as faithful to his blue collar roots and then become corrupted. Ben accidently discovers just how corrupt his cousin is. The corrupt scheme would ultimately result in good for the area, so I was trying to explore how much a person could compromise and still consider himself "good" and true to self and principles.There were a number of other complications to Ben uncovering the scheme. By the end of the novel, he was going to walk away from his job, home, history and start over in Myrtle Beach. I eventually decided to create Magnolia Beach rather than use Myrtle Beach for the setting because of all the sprawl and development clutter which complicated consistency of description and became a constant headache. I did some very rough drafts of this novel, probably around 180 to 200 pages, and eventually set them aside and just put Ben Decovic in Magnolia Beach and in his patrol car and started LATE RAIN.

#2

THE WORK OF HANDS for way too long has been my albatross. I had done two completely different versions of the novel for Crown after A CHOICE OF NIGHTMARES came out in 1991. I was just finishing a long (500 page) new draft of the novel when my editor got downsized, and Crown cancelled the book and my contract. At that point, having already drafted over a thousand pages with the three drafts, I just set it aside and forgot it. I worked on a couple other novel projects and was not happy with them or where they were headed. At that point anything resembling a writing career had pretty much evaporated, so I decided to jump blindly into a new project and wrote the opening line to THE LONG FALL and had no idea what it meant or who the characters were. The longest draft of THE LONG FALL was 450 pages (Jimmy Coates got in quite a bit of trouble), and I eventually decided to streamline the plot and brought it in at its published length of around 230 pages. I had never quite forgotten THE WORK OF HANDS during all this and kept messing with notes and ideas for a new version. I eventually started a completely new version of the novel right as LATE RAIN was accepted. I have done two drafts now and am closing in on finishing the third draft of the novel. I hope to have it done by early to mid-fall and in the hands of my agent. The new version barely resembles any of the earlier drafts, but hopefully I'll be able to ditch the albatross on this retelling.

James Sallis responded:

1. Found out there wasn't enough story in the box. (The idea, for me, was schematic and too limiting.) Significant parts of it found their way into the story "Concerto for Violence and Orchestra," a few bits and pieces into novels.Ken Bruen responded:

2. Stalled out at 80 pages or so, mainly, I think, due to relocation, life changes, and concentrating on the Lew Griffin novels. Still claim from time to time that I'm going back to it. Yeah, right.

3. Will be out next year from Walker, No Exit and others. The draft was completed about the time I wrote Drive, but there were structural problems. This one, I knew I'd get back to, and finally -- after four or five other novels -- did.

The children's book became a trilogy, and is at the cross roads ofFinally Duane Swierczynski responded:

Will it be a TV series?

Or

published first in book form.

1st time ever I got to tell my agent

You decide!

He's currently ..... deciding

Wish I had something more exciting for you, but the Dydak project is as dead as Dillinger. For a while there, I thought a spin-off might be fun. But this was before we saw a whole wave of crime-scene cleanup stories, including Charlie Huston's excellent MYSTIC ARTS OF ERASING ALL SIGNS OF DEATH. Which kind of killed it for me.Are you guys aware of any other lost novels? Novels that were mentioned in interviews or publicity material but never were released?

But who knows… maybe they'll have a cameo in a future Philly-set novel.

Sunday, July 29, 2012

Ding-Dong this genre is dead

by: Joelle Charbonneau

Cozies are dead.

Chick-lit is dead.

Romantic suspense is dead.

Science fiction is dead.

Dystopian is dead.

Private eye novels are dead.

I just finished attending a conference this weekend. There were workshops, pitch appointments,

award ceremonies, publisher parties and lots of chat amongst friends. There was also lots and lots of discussion

about the state of publishing.

It never fails that at every writers conference I attend, I

hear that a certain genre that was once incredibly popular is now completely

tanked. Dead. No longer will anyone buy that genre. If you write in that genre you’d better

switch genres or choose to go a non-traditional publishing route. I watch writers’ eyes widen in fear as they

realize the months or years they’ve spent working on their vampire novel or

their Georgian-set Historical has all been wasted. They shrug as if they don’t care, but I see

their muscles clench and the sadness lurking behind the smile.

OY!

Perhaps I shouldn’t say this, but no genre is ever

dead. No time has ever been wasted. Whether you are pursuing traditional or

self-publishing, readers are out there waiting to discover new stories in the

genre that has been declared null and void.

Industry professionals who speak confidently about a genre

being dead don’t really mean that it is not a viable option any longer. (Although that is typically what many, maybe

even most authors take away from the conversation. What they are saying is that a genre which in

recent years had seen a huge upswing in demand has now contracted a bit. It’s not that people aren’t buying books in

that genre, but they bought so many books in that genre over a set number of

years that the market has become oversaturated.

Take vampires. After

Twilight, publishers were buying vampire books in droves. They were HOT, HOT, HOT. Publishers wanted more vampires. Cooler vampires. Sparkly vampires.

And then they didn’t.

Suddenly, vampires were overdone. Now they wanted the next cool paranormal creature. Zombies.

Werewolves. Dragons. Faeries.

Angels. Demons. One year’s cool creature is next year’s

“Don’t send it. We’ve already got enough

of it.” critter.

And yet…while vampires “died” five years ago for publishers,

there are still books being published with vampire characters. So, clearly, the reports of their demise have

been greatly exaggerated. Right?

When a genre “dies” it doesn’t mean that no one is buying

that genre anymore. It doesn’t mean that

your book can’t sell or that readers don’t want to read you. It just means that what once was an easy sell

two years ago becomes a tougher sell now.

But it CAN sell.

Take my young adult novel, THE TESTING. Dystopian died about a year ago. Not because readers weren’t reading it or because

there weren’t books still coming out in that genre. It was because it was the genre every

publisher bought dozens and dozens of projects in a short period of time. Both my agent and I knew the book would be

harder to sell now that it would have been had I thought to write the sucker

two years before.

Even knowing it would be a tough sell, I wrote the

book. I wanted to write the book. My agent loved the book and pitched it. Several publishers turned us down without

even reading the book because the dystopian YA genre was dead. But most editors read the book. I’m guessing many of them did so with an

eye-roll because….drum roll please….the genre was dead. But they read it. A lot of them really liked it. Several loved it. The book and the rest of the trilogy sold.

Just because a genre is dead doesn’t mean you should abandon

it. It just means it might be harder to

sell to a traditional publisher or to attract notice if you self-publish the

book. But good stories are always being

looked for. And no genres ever really

die.

So, if you are going to a conference and you hear your genre

is dead…don’t shake your head with disappointment. Take it as a challenge. Make your writing and your story so strong

and people have to take notice. And

remember…the genres that fade today are the ones that rise from the ashes and

take the world by storm in the future.

No genre ever stays dead for long.

Saturday, July 28, 2012

Too Dazzling and the Anniversary Trick

by

Scott D. Parker

Sometimes, as a creative, you have to be a mental magician to get things done. As I continue documenting some of the struggles I've been having recently, I have two examples from this past week that illustrate this point and that rather cryptic title.

The Dazzling Dilemma

My wife is a jewelry artist. She makes beautiful, intricate, wearable works of art and has a great time doing so. As she writes on her website, she likes her art to make a connection with people. While she primarily makes jewelry for women, she does do the occasional piece for men. I wear a simple silver linked bracelet and it is often the one thing I have on hand to show folks what my wife does for a living.

For my wife, however, what piece of jewelry to wear can be a dilemma. I mean, come on: she's a jewelry artist, right? She takes great care and consideration which piece of her jewelry she wears to certain events since, you know, she wants to represent herself well. We had a day off on Tuesday where we had a meeting to attend. We were all ready to go, but my wife was trying to figure out exactly what she wanted to wear with her outfit. She tried on and discarded a half dozen pieces before settling on a nice turquoise necklace. She turned to me and said, "It's funny that I sometimes have such a hard time picking out just the right thing because I always want to dazzle people."

Her statement struck me to the core of my writing self. My writing style, such as it is, is one focused on flash. I'll admit that. While I don't necessarily go for verbal gymnastics like Michael Chabon or Jonathan Franzen, I still like the fancy, flowery writing. But when I write a basic scene or story, I have, to date, tended to consider it not good if it wasn't, well, dazzling. It was a realization I made this week and, as it applies to my writing, I decided to just tell the story and, upon *subsequent* revisions, I can add in the flowers. But I will not let the flowers get in the way of the initial output.

The Anniversary Trick

I've long said that it's taken me longer to *not* write my next book than it took me to write my first one. When I wrote that first novel, I kept all of my notes in one of those black-and-white marble-looking composition book. Not only was that comp book the store house of my novel notes, it was where I kept all of my motivational messages to myself.

Recently, I opened that comp book again to review how I started and noticed that I began that first novel on 27 July 2005. Well, thought I, why not kick off the new project on the very same day in 2012. And, since I made a notation of when I completed the first novel, I have given myself a simple goal: complete the next book in the same time or less. I'm big on symmetry and figured I'd like to measure myself against…myself.

Yes, I know these two things are mere mental tricks and the fundamentals of sit-and-write still rule the day, but, sometimes, we creative types need a little extra.

Y'all do any mental tricks to help you keep writing?

Scott D. Parker

Sometimes, as a creative, you have to be a mental magician to get things done. As I continue documenting some of the struggles I've been having recently, I have two examples from this past week that illustrate this point and that rather cryptic title.

The Dazzling Dilemma

My wife is a jewelry artist. She makes beautiful, intricate, wearable works of art and has a great time doing so. As she writes on her website, she likes her art to make a connection with people. While she primarily makes jewelry for women, she does do the occasional piece for men. I wear a simple silver linked bracelet and it is often the one thing I have on hand to show folks what my wife does for a living.

For my wife, however, what piece of jewelry to wear can be a dilemma. I mean, come on: she's a jewelry artist, right? She takes great care and consideration which piece of her jewelry she wears to certain events since, you know, she wants to represent herself well. We had a day off on Tuesday where we had a meeting to attend. We were all ready to go, but my wife was trying to figure out exactly what she wanted to wear with her outfit. She tried on and discarded a half dozen pieces before settling on a nice turquoise necklace. She turned to me and said, "It's funny that I sometimes have such a hard time picking out just the right thing because I always want to dazzle people."

Her statement struck me to the core of my writing self. My writing style, such as it is, is one focused on flash. I'll admit that. While I don't necessarily go for verbal gymnastics like Michael Chabon or Jonathan Franzen, I still like the fancy, flowery writing. But when I write a basic scene or story, I have, to date, tended to consider it not good if it wasn't, well, dazzling. It was a realization I made this week and, as it applies to my writing, I decided to just tell the story and, upon *subsequent* revisions, I can add in the flowers. But I will not let the flowers get in the way of the initial output.

The Anniversary Trick

I've long said that it's taken me longer to *not* write my next book than it took me to write my first one. When I wrote that first novel, I kept all of my notes in one of those black-and-white marble-looking composition book. Not only was that comp book the store house of my novel notes, it was where I kept all of my motivational messages to myself.

Recently, I opened that comp book again to review how I started and noticed that I began that first novel on 27 July 2005. Well, thought I, why not kick off the new project on the very same day in 2012. And, since I made a notation of when I completed the first novel, I have given myself a simple goal: complete the next book in the same time or less. I'm big on symmetry and figured I'd like to measure myself against…myself.

Yes, I know these two things are mere mental tricks and the fundamentals of sit-and-write still rule the day, but, sometimes, we creative types need a little extra.

Y'all do any mental tricks to help you keep writing?

Friday, July 27, 2012

Re-post - Emotional Rescuse

By Russel D McLean

Russel is a little behind this week, so this post originally appeared at the brilliant Detectives Beyond Borders Website to promote The Lost Sister when it launched in the US. With Father Confessor due out soon, it seemed an appropriate post as once again, Father Confessor - due out in September - is as much concerned with the emotional states of its protagonist as it is with the action (which involves people being thrown through windows and a full on police raid - just to tease you!)

Being a Scotsman, I was the perfect person for Peter Rozovsky to ask about the price of a gin and tonic at 2010’s San Francisco Bouchercon. After all, we do like to know where our money’s going and I can tell you this: those drinks were expensive.

How did I know?

I didn’t need two litres of Irn Bru* to recover after a night in the bar.

But I admire Peter for more than just his ability to sense when he’s being overcharged at a bar. His dedication to the world of crime fiction is to be truly admired, so when he asked me to guest here on DBB as part of my blog tour promotion for the US release of The Lost Sister, I jumped at the chance.

After all, he’s one of the people who got the book, in my humble estimation. In his recent critique of the novel, Peter picked up on more than a few points that I felt were absolutely vital to what I was trying to do with the novel. In particular, he picked up on the book being about emotions.

I am not – and this will be clear to anyone who’s heard me wax lyrical on the subject – a fan of what I see as “puzzle” mysteries, where the object is to solve whodunit or to merely catch the killer (you might as well be trying to catch the pigeon along with Dick Dastardly and Mutley for all that it eventually matters). While these things can indeed be part and parcel of a good crime story, I’ve always been more interested in the emotional states of the invested parties. If there’s a mystery I’d like to solve, it’s the mystery of why people react the way they do in certain situations.

The thrill of a good crime story for me is seeing the ways in which characters react to unusual and unsettling situations. The measure of a character for me is in the way they are affected either by direct involvement with or being witness to something unusual, something that breaks the status quo. Whether or not that status quo is eventually restored is less important to me than uncovering the ways in which people try to pick up their lives.

I guess that’s why I don’t write about a police officer. There is a natural degree of detachment that comes with the police officer as an authority figure that never appealed to me as a writer. A private investigator falls midway between being a civilian and having a professional interest in a case. They have a clear goal, a mission, and yet they are not so bound by rules and procedure as the copper might be.

They can walk where uniforms fear to tread.

There’s also the fact that having an investigator as your protagonist means you can come at a case sideways. A copper will always have to investigate after a crime. They are rarely in the midst of the transgression. A PI can never start with a body. They are not police and they should not be used as a rogue substitute. Their professional remit is different.

More personal.

More emotive.

More involved.

The eye allowed me to adopt an investigative stance while still looking at the way in which people are affected by crime and transgressive acts. McNee’s own emotions are as much of a puzzle to him as those of others. His own motivations require as much interrogation as those who fall under his professional gaze.

I’ve said it many times before that crime fiction is the perfect genre. That it allows authors to not only tell a story that moves, that twists, that surprises and thrills, but also to lay deeper groundwork. The nature of crime is naturally emotive and through characters and their attitudes, crime can explore issues of personal morality, of value, of empathy and so much more. In short, if we want to, we can beat the literary boys at their own game (and we often do).

So yes, The Lost Sister is a novel about a man searching for a missing girl. It is a novel about some very dangerous people. There are scenes of violence. There are plot twists and misdirections.

And at the same time, as Peter said, The Lost Sister is a novel about emotions. About loss. About the search for a kind of redemption and whether such a thing is even possible.

You can read it as one or the other. Or both. I just hope you enjoy it.

*Irn Bru is Scotland’s best hangover cure. Unofficially. Officially it’s a delicious fizzy beverage. The hangover cure’s just a side effect.

Russel is a little behind this week, so this post originally appeared at the brilliant Detectives Beyond Borders Website to promote The Lost Sister when it launched in the US. With Father Confessor due out soon, it seemed an appropriate post as once again, Father Confessor - due out in September - is as much concerned with the emotional states of its protagonist as it is with the action (which involves people being thrown through windows and a full on police raid - just to tease you!)

Being a Scotsman, I was the perfect person for Peter Rozovsky to ask about the price of a gin and tonic at 2010’s San Francisco Bouchercon. After all, we do like to know where our money’s going and I can tell you this: those drinks were expensive.

How did I know?

I didn’t need two litres of Irn Bru* to recover after a night in the bar.

But I admire Peter for more than just his ability to sense when he’s being overcharged at a bar. His dedication to the world of crime fiction is to be truly admired, so when he asked me to guest here on DBB as part of my blog tour promotion for the US release of The Lost Sister, I jumped at the chance.

After all, he’s one of the people who got the book, in my humble estimation. In his recent critique of the novel, Peter picked up on more than a few points that I felt were absolutely vital to what I was trying to do with the novel. In particular, he picked up on the book being about emotions.

I am not – and this will be clear to anyone who’s heard me wax lyrical on the subject – a fan of what I see as “puzzle” mysteries, where the object is to solve whodunit or to merely catch the killer (you might as well be trying to catch the pigeon along with Dick Dastardly and Mutley for all that it eventually matters). While these things can indeed be part and parcel of a good crime story, I’ve always been more interested in the emotional states of the invested parties. If there’s a mystery I’d like to solve, it’s the mystery of why people react the way they do in certain situations.

The thrill of a good crime story for me is seeing the ways in which characters react to unusual and unsettling situations. The measure of a character for me is in the way they are affected either by direct involvement with or being witness to something unusual, something that breaks the status quo. Whether or not that status quo is eventually restored is less important to me than uncovering the ways in which people try to pick up their lives.

I guess that’s why I don’t write about a police officer. There is a natural degree of detachment that comes with the police officer as an authority figure that never appealed to me as a writer. A private investigator falls midway between being a civilian and having a professional interest in a case. They have a clear goal, a mission, and yet they are not so bound by rules and procedure as the copper might be.

They can walk where uniforms fear to tread.

There’s also the fact that having an investigator as your protagonist means you can come at a case sideways. A copper will always have to investigate after a crime. They are rarely in the midst of the transgression. A PI can never start with a body. They are not police and they should not be used as a rogue substitute. Their professional remit is different.

More personal.

More emotive.

More involved.

The eye allowed me to adopt an investigative stance while still looking at the way in which people are affected by crime and transgressive acts. McNee’s own emotions are as much of a puzzle to him as those of others. His own motivations require as much interrogation as those who fall under his professional gaze.

I’ve said it many times before that crime fiction is the perfect genre. That it allows authors to not only tell a story that moves, that twists, that surprises and thrills, but also to lay deeper groundwork. The nature of crime is naturally emotive and through characters and their attitudes, crime can explore issues of personal morality, of value, of empathy and so much more. In short, if we want to, we can beat the literary boys at their own game (and we often do).

So yes, The Lost Sister is a novel about a man searching for a missing girl. It is a novel about some very dangerous people. There are scenes of violence. There are plot twists and misdirections.

And at the same time, as Peter said, The Lost Sister is a novel about emotions. About loss. About the search for a kind of redemption and whether such a thing is even possible.

You can read it as one or the other. Or both. I just hope you enjoy it.

*Irn Bru is Scotland’s best hangover cure. Unofficially. Officially it’s a delicious fizzy beverage. The hangover cure’s just a side effect.

Thursday, July 26, 2012

As You Are

By Jay Stringer

So I have a book out this week. But you already know that. You already bought it. Right? RIIIGHT? Good, we're cool.

When my wife is in music journalist mode, she'll often ask me if I want to listen to whatever new act or album she's writing about. Sometimes I'll say yes, sometimes I'll shrug and pick my nose, sometimes I'll threaten to burn down the flat if she ever brings that band near me again. An act that I'll always say yes to hearing is Dave Hughes & The Renegade Folk Punk Band, and they have a new single coming out so you can all say yes to them too.

So I have a book out this week. But you already know that. You already bought it. Right? RIIIGHT? Good, we're cool.

When my wife is in music journalist mode, she'll often ask me if I want to listen to whatever new act or album she's writing about. Sometimes I'll say yes, sometimes I'll shrug and pick my nose, sometimes I'll threaten to burn down the flat if she ever brings that band near me again. An act that I'll always say yes to hearing is Dave Hughes & The Renegade Folk Punk Band, and they have a new single coming out so you can all say yes to them too.

When I blurbed for someones ebook recently I paid them the best and simplest compliment I could think of, which was that he wrote the stories I wanted to read. For Dave Hughes & The RFPB, I could say they play the kind of music I want to hear.

Hughes writes and sings about real people and real things, and the Renegade Folk Punk Band fill out the sound with just enough of a raw edge to keep you guessing about where the song goes next. Steve Van Zandt once said of the E Street Band, "you can take the band out of the bar, but you can't take the bar out of the band," and whether you're listening to the RFPB on CD or watching them play a stage, you always get the same fun and free experience; they're always stood next you with their instruments wanting you to have a good time. There's always that feeling, like The Replacements just before Bobby Stinson did a guitar solo, or the Pogues just before Shane took another sip, of something about to cut loose and run.

Their new single, As You Are, is the most assured and professional recoding I've heard from them to date, but hasn't lost any of the raw fun that makes them tick. It features piano from another of our best acts, Chris T-T, and will be available from Itunes, Spotify and Bandcamp on 13/08/12. Keep an eye on Dave's website or follow him on twitter for more news on the album, In Death Do We Part?, which is going to get a lot of people excited.

Dave Hughes On Tour;

28/07 Newcastle, The Telegraph Bar

29/07 Manchester, The Bay Horse

30/07 York, Stereo

02/08 Blackpool, Rebellion Festival

28/07 Newcastle, The Telegraph Bar

29/07 Manchester, The Bay Horse

30/07 York, Stereo

02/08 Blackpool, Rebellion Festival

Wednesday, July 25, 2012

Sandra Seamans: The Interview

By Steve Weddle

If you know anything about short stories and crime fiction, then you already know Sandra Seamans. Her blog, My Little Corner, is a must-read -- as are her stories.

|

| Image updated: 30May2019 |

I've worked with Sandra on a couple of projects -- the very first Needle mag and the DISCOUNT NOIR collection Patti Abbott and I edited.

Sandra was nice enough to answer some of my questions about writing style and short stories and much more.

Steve: Your “My Little Corner” blog claims to be a place for your “scattered thoughts.” In fact, your site provides a great deal of real news about what’s going on in the fiction community. From new publishers to contest and anthology calls, your site is one of the most useful sites for short story writers. How did you get to this point?

Sandra: Pretty much by accident. I started the blog without any idea of what to do with one and no expectation that anyone would actually read it. Once I figured out how to post links I started linking to online zines to make it easier for me to find markets when I had a story to sell and also to find stories to read. When I decided to clean out my email files, I discovered a whole slew of zine links and market listings which I added to the blog. It seemed a shame to stop there, so I just kept adding new links as I found them.

I always appreciated when other writers shared markets with me, so the blog was a way for me to pass that kindness forward. It's also been a joy for me to watch other writers get published in those new markets. It's such a big world out there on the 'net that having links in one place makes it easier for writers to find the type of market they're looking for.

Along the way I realized that by focusing only on mystery markets, crime writers were missing out on other outlets for their work. That mystery/crime stories fit in all genres, especially in many of the horror markets. So I began adding anthology calls, contest, and writing advice links for all the genres. It's been a lot of fun for me and hopefully useful to other writers.

Steve: Benjamin Whitmer, another of my favorite writers, has called your COLD RIFTS “a fierce, sorrowful” book of stories. How did you choose these stories for this collection?

Sandra: With a great deal of hair pulling. I knew they all needed to be dark stories because that's what Snubnose Press publishes. Since most of my work has been published online I felt the need to make the bulk of the collection new stories. I had six new stories and a half-written novella (which turned into a novelette) in my files that fit the bill. Besides finishing the novelette, I also wrote two more new stories and lengthened a pair of published flash stories. The rest was just a matter of deciding which published pieces would compliment the new work.

Putting them into some kind of order was the tricky part. I spent hours writing down lists of stories, their themes, lengths, male or female protags. I finally wound up loosely putting them together in groups of four - two dark stories, one paranormal and one humorous. What I hoped for in this arrangement was to break up the intensity of the darkest crime stories so that readers didn't feel like they were being pummeled to death with disaster. One other thing I did was mix in a good dose of male protags so the male readers won't be overwhelmed with a feminine point of view. I didn't want the collection to appeal strictly to women, I wanted something for everyone to enjoy

Steve: At a recent Mystery Writers of America meeting, Snubnose Publisher Brian Lindenmuth talked about your book in addition to some of the others that indie press is publishing. How helpful has it been to be in a community of like-minded readers and writers?

Sandra: It's like having your own private cheerleaders. They're always there with an encouraging word and a helping hand when you need it.

Steve: You’ve had stories published nearly everywhere, at places that continue and places that have moved on – Shred of Evidence, Pulp Pusher, Scalped ezine. How has the market for short story writers changed over the past few years?

Sandra: The biggest change has come in the last year or so with e-publishing. More and more small presses are putting together anthologies and writers are getting a percentage of the profits. The amounts aren't huge but it beats constantly giving it away for free or having it sit in a drawer collecting dust.

I also love that print magazines are making a comeback. We've got Needle, Pulp Modern, and Grift which are publishing some great stories. And it's not just the mystery genre, there's new horror and sci-fi/fantasy print zines showing up.

The online zines are always in flux and I suspect always will be. What I have noticed is that some of them are starting to put together "best of" anthologies and e-pubbing them which puts the stories in front of a larger audience. Others, like The Big Click, Noir Nation, Spinetingler and ThugLit, are putting out new issues in this manner, which helps pay their bills and put a little jingle in the writer's pockets.

Steve: GRIMM TALES, an Untreed Reads publication, is a collection of stories in which top authors retell a Grimm tale in modern terms. How did your story come about?

Sandra: The minute John Kenyon put up the challenge to rewrite a fairytale into a crime story, I was in. Yeah, I’m a fairytale freak. I also knew I wanted to do something different. There are only so many variations of the usual suspects that you can write. I found a website that had many of the Grimm's published. Reading down through the list of titles "The Blue Light" caught my eye. It was the story of a Soldier who'd fought for the King and when he was wounded and not as useful, the King sent him away. Through a meeting with a witch he finds a way to get his revenge on the King - perfect setup for a crime story. I used the basics of the fairytale but turned the soldier into a cleanup man for a mob boss, gave him some rules he lived by and off we went. It was a fun story to write.

Steve: You’ve been writing stories for years, of course. Have your habits of writing changed? Are you quicker? More deliberate? Has it gotten easier?

Sandra: In some ways it’s easier. The blank page doesn’t scare me as much as it used to. I’ve also discovered that every idea that pops into my brain won't always make a good story, but the time spent writing and going nowhere isn’t wasted. Bits and pieces of those “useless” stories generally find there way into other stories that do work.

I’ve also learned to take my time, to think more about the character’s motives instead of just charging ahead into the action. The hardest part for me is setting the story aside for a week or two then going back. Setting the story aside allows my brain the freedom to mull over what I’ve written and consider other options or new scenes that would open the story up more or help explain better what’s going on. When I finally reopen the file, I usually have several pages full of notes and new scenes sketched out.

Each new story, at least for me, is a learning process. I’m learning to take my time instead of just banging away, then having to cut out half of what I’ve written. The hardest part is learning to trust my instincts. Inside, you know what is or isn’t working. You just have to trust that inner voice. Trust that it knows you're doing what’s right for the story when you hit the delete key.

Steve: In the Age Of The Laptop, the “room of one’s own” idea seems to be fading away. People write in coffee shops, of all places.. Do you have a favorite place to write or are you one of those people who scrawls down a complete story anywhere?

Sandra: I have a small office in the house where I work on my computer. I don’t have a laptop that moves from room to room but you’ll find notepads (junk mail envelopes make great note paper, too) and pens in just about every room where I’ve scrawled down ideas for new stories, bits of dialogue for the current wip, or random scenes that I think will take an old story into a new direction.

Living in the country, there’s no nearby coffee shops, so it’s just me at home with my Mr. Coffee to keep me company.

Steve: What short story writers should people be reading now?

Sandra: There's so many of them, it's difficult to choose, and everyone's taste in stories is so different. Some of the writers I've enjoyed lately are Charles Dodd White, Seamus Scanlon, and Misty Skaggs. These writers tend toward the more literary side of my short story reading. For the crime/mystery group I'd say Art Taylor, Thomas Pluck, Jane Hammons, Libby Cudmore and Jen Conley. And of course, there are a hundred others out there that everyone should be reading, just click on any online zine and you’ll find them.

Steve: What are you working on now?

Sandra: I'm always working on the next story. Recently, I was invited to submit a story to a charity anthology with an end of the world theme. I was stumped until I came across an old micro-flash that I’d written and believe, that with a bit of research, it will work into a good short story. One of the joys of flash fiction is that there’s always more story to tell.

I also have several “finished” stories simmering in their file folders that need to be opened. They just need a few more scenes added and a bit of polishing before they get kicked out the door. And then there's the Western that I’m working on. I know pretty much how it’s going to unfold, it’s just a matter of getting it from my head to the page.

Check out My Little Corner to keep up-to-date on all the crime fiction happenings.

Labels:

author interview,

interview,

Needle,

Sandra Seamans,

Snubnose Press,

Steve Weddle

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

Character.... It's all about Character, except in film..

Like just about everyone else (EXCEPT YOU), I saw THE DARK KNIGHT RISES this weekend. I really liked the film and for the most part felt it was a quality movie and a well-done end to a superb trilogy.

But, it wasn't without its flaws.

Most of its flaws came at the cost of character. The movie--hell, the series--takes its time setting up aspects of Batman and his surrounding characters and then in the last ten minutes of the movie ignores them. It was enough to set off alarm bells in my brain, and knocks the movie from AWESOME HOLY CRAP SPECTACULAR down to well, I really enjoyed that.

But the problem is even bigger than the Batman series, it's a film problem.

It strikes me that film is more about the moment. Whenever people talk about movies they always talk about "that scene." "REMEMBER THAT PART WHERE?" Ignoring the fact that that part is only so cool because it ignores everything that came before it for the sake of the scene. Character motivation doesn't matter. Reality doesn't matter.

All that matters is the shot, the scene.

Head of a horse in movie producer's bed? Nevermind that Tom Hagen had to sneak back into the estate, chop off the head of a horse without anyone noticing, then sneak back into the mansion... WITH A BLOODY HORSE'S HEAD.. and put it in the bed without the movie producer waking up.

But come on, everyone remembers that point and points to it as cool.

And we're used to it. The scene outweighs the character. It's so cool, that you can get into years long arguments because there are a clues in a scene that make no sense in to the character or even the plot.

Take, for example, the end of THE SOPRANOS.

There are a lot of people who think Tony dies at the very end. That when the screen goes blank, it's because Tony does. They point to a painting on the back wall of Holsten's (which is 3 minutes from my house... great ice cream... painting isn't really there though). They point to the communion style way the Soprano family eats their onion rings. They point to Members Only jacket. Tony dies, they say. There's no other answer.

.......

What???

No other answer?

Did you listen to the entire episode before that? Did you pay any attention to the fact that Tony and crew take place of all family business? That everyone is either dead or struck a deal with Tony to end the mob war? That no one is left to kill Tony? That hired killers do things for money, not revenge...? That the Russian didn't know Tony existed? That the two hired guns from season 1 were taken care of? That we didn't even know Frank Vincent had a brother, so how could Members Only be Frank Vincent's brother out for revenge? If you look at the end of 90% of all the other episodes, the theme of the series, and what the characters, believe... LIFE GOES ON?

But that doesn't make the scene cool.

So he has to die. That's a cool scene.

Movies... TV (which is changing as it's becoming more of a writer driven medium) have to become about more that a shot, an angle, or a scene. Reviewers need to focus on the whole picture. Directors need to sacrifice their wonderful shot if it doesn't fit who the characters are.

Focus on story.

Focus on character.

It will be better off.

But, it wasn't without its flaws.

Most of its flaws came at the cost of character. The movie--hell, the series--takes its time setting up aspects of Batman and his surrounding characters and then in the last ten minutes of the movie ignores them. It was enough to set off alarm bells in my brain, and knocks the movie from AWESOME HOLY CRAP SPECTACULAR down to well, I really enjoyed that.

But the problem is even bigger than the Batman series, it's a film problem.

It strikes me that film is more about the moment. Whenever people talk about movies they always talk about "that scene." "REMEMBER THAT PART WHERE?" Ignoring the fact that that part is only so cool because it ignores everything that came before it for the sake of the scene. Character motivation doesn't matter. Reality doesn't matter.

All that matters is the shot, the scene.

Head of a horse in movie producer's bed? Nevermind that Tom Hagen had to sneak back into the estate, chop off the head of a horse without anyone noticing, then sneak back into the mansion... WITH A BLOODY HORSE'S HEAD.. and put it in the bed without the movie producer waking up.

But come on, everyone remembers that point and points to it as cool.

And we're used to it. The scene outweighs the character. It's so cool, that you can get into years long arguments because there are a clues in a scene that make no sense in to the character or even the plot.

Take, for example, the end of THE SOPRANOS.

There are a lot of people who think Tony dies at the very end. That when the screen goes blank, it's because Tony does. They point to a painting on the back wall of Holsten's (which is 3 minutes from my house... great ice cream... painting isn't really there though). They point to the communion style way the Soprano family eats their onion rings. They point to Members Only jacket. Tony dies, they say. There's no other answer.

.......

What???

No other answer?

Did you listen to the entire episode before that? Did you pay any attention to the fact that Tony and crew take place of all family business? That everyone is either dead or struck a deal with Tony to end the mob war? That no one is left to kill Tony? That hired killers do things for money, not revenge...? That the Russian didn't know Tony existed? That the two hired guns from season 1 were taken care of? That we didn't even know Frank Vincent had a brother, so how could Members Only be Frank Vincent's brother out for revenge? If you look at the end of 90% of all the other episodes, the theme of the series, and what the characters, believe... LIFE GOES ON?

But that doesn't make the scene cool.

So he has to die. That's a cool scene.

Movies... TV (which is changing as it's becoming more of a writer driven medium) have to become about more that a shot, an angle, or a scene. Reviewers need to focus on the whole picture. Directors need to sacrifice their wonderful shot if it doesn't fit who the characters are.

Focus on story.

Focus on character.

It will be better off.

Monday, July 23, 2012

Origin stories and reboots

After last weeks dense post I'm going to be shorter this week.

Earlier in the year I saw The Avengers at the theater with the boy and this past week we saw The Amazing Spider Man. Like a lot of other people this weekend Sandra and I went and saw The Dark Knight Rises. In spite of some nits to pick (Bane's mask did Hardy no favors, the fight choreography seemed sloppy, Bane beating Batman down should/could have been more definitive [Hardy can pull it off just look at Bronson and Warrior], and it felt like Nolan was always choosing to be up close and didn't want to pull the camera back), which I always have, I enjoyed the film and look forward to seeing it again with the boy and the reluctant daughter.

The first thing that I'd like to say is that I like the idea of reboots and have said as much before. I think that new teams of filmmakers, at different times, should have the opportunity to put their fingerprint on a character, series or franchise. Which means I'd love to see Idris Elba as James Bond, or Rob Zombie make a film set in the Star Wars universe (EU movies should be a thing) or Quentin Tarantino direct a Bond film. All of which is to say that as much as I love the Nolan trilogy of Batman films I look forward to seeing what someone else can/will do with it. What the next group does with their Batman movie will not diminish Nolan's accomplishment. Especially with such a wealth of material to work from.

Side note #1: Please, please, please for a Nightwing movie set in Nolan's Gotham.

Side note #2: Gotham Central would be a kick ass TV show.

The second thing that I've been thinking about is origin stories and if we still need them. And if we do need them can they be told in a narrative shorthand. As much as I liked the new Spider Man movie I'm not convinced that I needed to see the origin story again since I saw it only 10 years ago.

Some might say that origin stories are necessary for those who aren't familiar with the character. I say that some of these characters origin stories are pretty well known.

Any movie where the origin story needs to be told is essentially two stories and two halves. The first story is the origin and unfolds over the first hour or so, with the foundation of the second story being laid. Then, in the second half, the story proper unfolds. A common complain with these movies is that the ending feels rushed. What if you could have more of that origin story time devoted to the story proper?

One of the successes of The Avengers is that the origin stories were already told for the characters so we got to spend a lot of time watching The Avengers be The Avengers. It's also one of the strengths of the Nolan Batman movies, we don't have to see Batman's origin in subsequent movies (and Nolan pokes fun at origin stories with Joker changing his around with each telling).

Tell me what you think.

Reboots, yay or nay?

Origin stories, yay or nay?

Thoughts on The Dark Knight Rises or my nits (or what were yours)?

Currently reading: The Spider's Cage by Jim Nisbet.

Earlier in the year I saw The Avengers at the theater with the boy and this past week we saw The Amazing Spider Man. Like a lot of other people this weekend Sandra and I went and saw The Dark Knight Rises. In spite of some nits to pick (Bane's mask did Hardy no favors, the fight choreography seemed sloppy, Bane beating Batman down should/could have been more definitive [Hardy can pull it off just look at Bronson and Warrior], and it felt like Nolan was always choosing to be up close and didn't want to pull the camera back), which I always have, I enjoyed the film and look forward to seeing it again with the boy and the reluctant daughter.

The first thing that I'd like to say is that I like the idea of reboots and have said as much before. I think that new teams of filmmakers, at different times, should have the opportunity to put their fingerprint on a character, series or franchise. Which means I'd love to see Idris Elba as James Bond, or Rob Zombie make a film set in the Star Wars universe (EU movies should be a thing) or Quentin Tarantino direct a Bond film. All of which is to say that as much as I love the Nolan trilogy of Batman films I look forward to seeing what someone else can/will do with it. What the next group does with their Batman movie will not diminish Nolan's accomplishment. Especially with such a wealth of material to work from.

Side note #1: Please, please, please for a Nightwing movie set in Nolan's Gotham.

Side note #2: Gotham Central would be a kick ass TV show.

The second thing that I've been thinking about is origin stories and if we still need them. And if we do need them can they be told in a narrative shorthand. As much as I liked the new Spider Man movie I'm not convinced that I needed to see the origin story again since I saw it only 10 years ago.

Some might say that origin stories are necessary for those who aren't familiar with the character. I say that some of these characters origin stories are pretty well known.

Any movie where the origin story needs to be told is essentially two stories and two halves. The first story is the origin and unfolds over the first hour or so, with the foundation of the second story being laid. Then, in the second half, the story proper unfolds. A common complain with these movies is that the ending feels rushed. What if you could have more of that origin story time devoted to the story proper?

One of the successes of The Avengers is that the origin stories were already told for the characters so we got to spend a lot of time watching The Avengers be The Avengers. It's also one of the strengths of the Nolan Batman movies, we don't have to see Batman's origin in subsequent movies (and Nolan pokes fun at origin stories with Joker changing his around with each telling).

Tell me what you think.

Reboots, yay or nay?

Origin stories, yay or nay?

Thoughts on The Dark Knight Rises or my nits (or what were yours)?

Currently reading: The Spider's Cage by Jim Nisbet.

Sunday, July 22, 2012

When fiction becomes reality

By: Joelle Charbonneau

I’m sad. My heart

aches as I’m certain yours does. Here at

Do Some Damage we are fans of fictional crime.

Fans of heroes and villains. We write

stories that often have violence at the core.

But when fiction becomes reality, it is time to step back, pause and

reflect.

As I’m sure you are away, this weekend was the opening of

the new Batman movie. I’m a huge comic

book movie fan and while I doubt my crowded personal life will allow me time to

see it in the theaters, I still anticipated the release of the movie. I smiled as I watch Twitter and Facebooks

posts leading up to the big day. I was

curious if opinions I respected would believe the movie to be as strong as its predecessors

and watched for the commentary.

Instead, I found tragedy.

A man wearing a gas mask threw tear gas into a packed theater

then opened fire. 12 dead. 11 critically wounded. Dozens physically injured. The shooter has been apprehended, although I

doubt anyone will ever understand why he made the choice to kill. The police that went to his home found trip

wires and explosive devices. Handmade

grenades. Accelerants designed to kill

whoever entered and potentially destroy the entire building and its residents. This sounds like the plot to a book or a

movie.

But it’s all too terribly real.

This is not a book where I root for the bad guy to be

brought low. It isn’t a movie where the

audience cheers when the hero triumphs.

Instead, there is only sadness, confusion and heartbreak.

I don’t know if the people that survived the shooting will

ever recover from the terror they must have felt. No matter how many psychiatrists weigh in, we

will never know the reasons for this unthinkable act that stole the lives of so

many. All we can do is pray for the families

of those who were lost, show our support to those that survived and in the

sadness cling to the hope that this senseless taking of lives will never happen

again.

To the people of Aurora,

Colorado—my thoughts and prayers

are with you all. My you find peace in the

days and months ahead.

Saturday, July 21, 2012

What 1,000 Words Looks Like

(As this week began, I had planned on writing about one subject: Batman and specifically the three movies Christopher Nolan directed. This post here was going to be offered next week. After the unspeakable tragedy in Colorado, today is not the day for that post. We here at Do Some Damage offer our sincerest condolences and prayers to the victims and to the families that now are absent a loved one. Writing about writing seems so trivial and, to a degree, it is. But it is on days like yesterday where we are all reminded of the preciousness of life and all the tribulations and triumphs we endure. Each one of us copes with tragedy in different ways, and writing, for many of us, is one of those methods. Whatever you do, do it with passion and intensity and joy and abandon with as much zeal and verve as you possess.)

Accountants do not need any tricks to do their job. Neither do oilfield engineers, carpenters, teachers, or bus drivers. In my day job as a technical writer, I also do not need very many tricks to get my job done. However, when it comes to writing fiction, something seems to happen. We get stuck, we don't know where to go, we may not be able to think up interesting plots, we may not be able to carve out the time, and any number of other things that get in the way. Why is that? Is it because of the inherent creative nature of what we do? Is it, perhaps, the muscle of the imagination is the thing that needs to be honed and exercised?

The most obvious way in which we fiction writers measure our progress is by word count, the number of words that we have imagined into existence. Naturally, if you were measuring yourself by word count, the most basic metric is the daily word count. And, in that sense, the myth of the 1,000 words per day writing pace has developed. This is a modern metric, not nearly the pace and the output of the old pulp masters, and yet, quite a bit faster than the pace of some modern literary authors who publish a big book once a decade. If you do the simple math, it goes something like this: if you write 1,000 words per day, you will write 365,000 words per year. Since most novels are roughly 90,000 words, it naturally falls that you could conceivably write three 90,000-word novels per year.

A few weeks ago, the New York Times ran a story about the new expectations of readers and how established authors are changing to meet demand. For certain name brand authors who publish one novel a year like clockwork, the article mentioned that publishing houses are beginning to wonder if these authors can't add in a novella, or short story, or a small e-book to fill in the gaps between novel publications. Having never published a best seller myself, I can't speak to what goes in to making one. But back to the 1,000 words per day metric, one would think that that is an achievable goal, or at lease one to strive for.

The late Ray Bradbury, who died in June, was a prolific author. No, he did not publish 3 books per year, but he did do something for much of his adult life that he advocates all writers do: write every day. Soon after he passed away, I pulled out my copy of his writing book, Zen and the Art of Writing. It was in this book where he advocated writing something––anything––per day. Here is one of the many money quotes from this book: “If you did not write every day, the poisons would accumulate and you would begin to die, or act crazy, or both. You must stay drunk on writing so reality cannot destroy you.”

Writing something every day isn't that difficult, really. If you want to be a writer, you just do it. But how does that compare with that modern 1,000-word metric? One of the arguments that have made for myself is that the thousand-word goal seems like a very high and threshold to reach. True, I don't *have* to meet that goal, but without setting some sort of goal, one would just meander, right? I mean, if you wrote a paragraph a day, you would be following Bradbury's advice, but you would not ever complete a novel.

So this past week, I did little experiment. I went back to my Harry Truman novel and selected a chapter at random. It turned out to be in early one, chapter 4 I think. I want to note two things: how long it took me to literally type one thousand words and how long it took me to type each page. So with a copy of chapter 4 next to me, I started typing. At the end of the first full-page (double-spaced), 6:15 had elapsed. By the end of the second page, I was at 12:16 and I completed the third by 18:30. It took me an additional 20 seconds to type the remaining few words to get me up to 1,000. It doesn't take a math genius to pretty much see the rate of typing, that being around 6 min. a page. As you may have already figured out, 1,000 words is approximately 3 pages of double-spaced typed manuscript with one-inch margins on the side.

Three pages. That's all. I was surprised when I saw those three pages printed out. In my mind, the entire chapter was around 1,000 words, and the idea of writing a chapter per day seemed quite daunting. In reality, I chapter is 7-1/2 pages long. That equals approximately 2500 words.

Now, your your response will be the obvious one: I knew exactly what you're typing and all you did was type. I did no creating. That's true, but if you examine the amount of time it took me to type those 1,000 words––19 min.––you'll realize that it's less than half hour. One would like to think that, given eleven min. to come up with a scene or a bit of dialogue, that you could easily type out the 1,000 words it could take to describe that scene in the next nineteen minutes.

Thirty minutes. Half an hour. When we talk about carving out time to write each and every day, my mind almost always goes in to the hour block of time. And, given our busy lives, I can honestly say that finding a hour a day can be challenging, even though I want to be a prose writer. That was how my reasoning went before this week: which hour of the day do I want to carve out to write 1,000 words? After my little experiment, I am rephrasing the question: what half an hour do I want to carve out each day to write 1,000 words?

While this might be easier said than done, my modus operandi of writing is via outline. My Truman novel was written with the complete outline before I started. Yes I revised along the way, but what having it outline gave me was a purpose for each writing session. I didn't have to think what I was going to write, I merely had to pick up the next index card in the outline and write that one scene.

In the years since my first novel, I have experimented with other types of writing regimens. To date, as I like to jokingly say, it is taking me longer not to write another novel that did take to write my first. I think it is time to go back to what I know works: outlining and producing. And, after the initial burst of creativity to create the outline, might it only take me a half an hour a day over 90 or so days to create a novel?

I'm looking forward to finding out the answer.

Accountants do not need any tricks to do their job. Neither do oilfield engineers, carpenters, teachers, or bus drivers. In my day job as a technical writer, I also do not need very many tricks to get my job done. However, when it comes to writing fiction, something seems to happen. We get stuck, we don't know where to go, we may not be able to think up interesting plots, we may not be able to carve out the time, and any number of other things that get in the way. Why is that? Is it because of the inherent creative nature of what we do? Is it, perhaps, the muscle of the imagination is the thing that needs to be honed and exercised?

The most obvious way in which we fiction writers measure our progress is by word count, the number of words that we have imagined into existence. Naturally, if you were measuring yourself by word count, the most basic metric is the daily word count. And, in that sense, the myth of the 1,000 words per day writing pace has developed. This is a modern metric, not nearly the pace and the output of the old pulp masters, and yet, quite a bit faster than the pace of some modern literary authors who publish a big book once a decade. If you do the simple math, it goes something like this: if you write 1,000 words per day, you will write 365,000 words per year. Since most novels are roughly 90,000 words, it naturally falls that you could conceivably write three 90,000-word novels per year.

A few weeks ago, the New York Times ran a story about the new expectations of readers and how established authors are changing to meet demand. For certain name brand authors who publish one novel a year like clockwork, the article mentioned that publishing houses are beginning to wonder if these authors can't add in a novella, or short story, or a small e-book to fill in the gaps between novel publications. Having never published a best seller myself, I can't speak to what goes in to making one. But back to the 1,000 words per day metric, one would think that that is an achievable goal, or at lease one to strive for.

The late Ray Bradbury, who died in June, was a prolific author. No, he did not publish 3 books per year, but he did do something for much of his adult life that he advocates all writers do: write every day. Soon after he passed away, I pulled out my copy of his writing book, Zen and the Art of Writing. It was in this book where he advocated writing something––anything––per day. Here is one of the many money quotes from this book: “If you did not write every day, the poisons would accumulate and you would begin to die, or act crazy, or both. You must stay drunk on writing so reality cannot destroy you.”

Writing something every day isn't that difficult, really. If you want to be a writer, you just do it. But how does that compare with that modern 1,000-word metric? One of the arguments that have made for myself is that the thousand-word goal seems like a very high and threshold to reach. True, I don't *have* to meet that goal, but without setting some sort of goal, one would just meander, right? I mean, if you wrote a paragraph a day, you would be following Bradbury's advice, but you would not ever complete a novel.

So this past week, I did little experiment. I went back to my Harry Truman novel and selected a chapter at random. It turned out to be in early one, chapter 4 I think. I want to note two things: how long it took me to literally type one thousand words and how long it took me to type each page. So with a copy of chapter 4 next to me, I started typing. At the end of the first full-page (double-spaced), 6:15 had elapsed. By the end of the second page, I was at 12:16 and I completed the third by 18:30. It took me an additional 20 seconds to type the remaining few words to get me up to 1,000. It doesn't take a math genius to pretty much see the rate of typing, that being around 6 min. a page. As you may have already figured out, 1,000 words is approximately 3 pages of double-spaced typed manuscript with one-inch margins on the side.

Three pages. That's all. I was surprised when I saw those three pages printed out. In my mind, the entire chapter was around 1,000 words, and the idea of writing a chapter per day seemed quite daunting. In reality, I chapter is 7-1/2 pages long. That equals approximately 2500 words.

Now, your your response will be the obvious one: I knew exactly what you're typing and all you did was type. I did no creating. That's true, but if you examine the amount of time it took me to type those 1,000 words––19 min.––you'll realize that it's less than half hour. One would like to think that, given eleven min. to come up with a scene or a bit of dialogue, that you could easily type out the 1,000 words it could take to describe that scene in the next nineteen minutes.

Thirty minutes. Half an hour. When we talk about carving out time to write each and every day, my mind almost always goes in to the hour block of time. And, given our busy lives, I can honestly say that finding a hour a day can be challenging, even though I want to be a prose writer. That was how my reasoning went before this week: which hour of the day do I want to carve out to write 1,000 words? After my little experiment, I am rephrasing the question: what half an hour do I want to carve out each day to write 1,000 words?

While this might be easier said than done, my modus operandi of writing is via outline. My Truman novel was written with the complete outline before I started. Yes I revised along the way, but what having it outline gave me was a purpose for each writing session. I didn't have to think what I was going to write, I merely had to pick up the next index card in the outline and write that one scene.

In the years since my first novel, I have experimented with other types of writing regimens. To date, as I like to jokingly say, it is taking me longer not to write another novel that did take to write my first. I think it is time to go back to what I know works: outlining and producing. And, after the initial burst of creativity to create the outline, might it only take me a half an hour a day over 90 or so days to create a novel?

I'm looking forward to finding out the answer.

Friday, July 20, 2012

Five Paragraphs of Russel

Russel D McLean

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

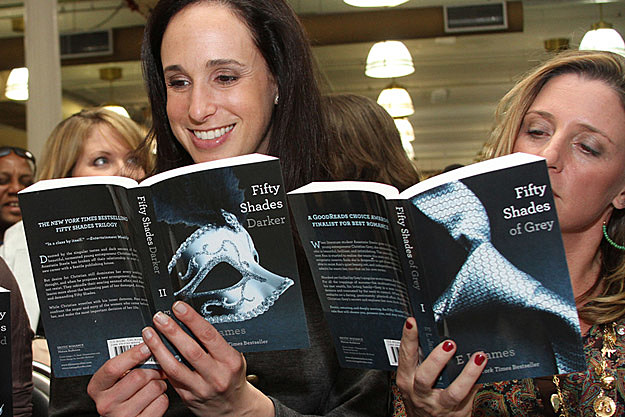

FIFTY SHADES OF GRAY is the book of the moment. Love it or hate it, its there and its not going anywhere very soon. People will talk about what it means in the cultural zeitgeist and try to make more of it than it really is (its a naughty book - there have always been and will always be naughty books, and most of them will be written with the same regard for the English language as SHADES, and that's fine) and others will decry or mock it. But the fact is that people are reading it so let's have a genuine cheer for Ms James and her success. Its what we all want and its what very few of us will get, so let's feel good for those that it happens to.